Contrapposto is an Italian term that means "counterpoise". It is used in the visual arts to describe a human figure standing with most of its weight on one foot, so that its shoulders and arms twist off-axis from the hips and legs in the axial plane.

Praxiteles of Athens, the son of Cephisodotus the Elder, was the most renowned of the Attica sculptors of the 4th century BC. He was the first to sculpt the nude female form in a life-size statue. While no indubitably attributable sculpture by Praxiteles is extant, numerous copies of his works have survived; several authors, including Pliny the Elder, wrote of his works; and coins engraved with silhouettes of his various famous statuary types from the period still exist.

Polykleitos was an ancient Greek sculptor, active in the 5th century BCE. Alongside the Athenian sculptors Pheidias, Myron and Praxiteles, he is considered as one of the most important sculptors of classical antiquity. The 4th century BCE catalogue attributed to Xenocrates, which was Pliny's guide in matters of art, ranked him between Pheidias and Myron. He is particularly known for his lost treatise, the Canon of Polykleitos, which set out his mathematical basis of an idealised male body shape.

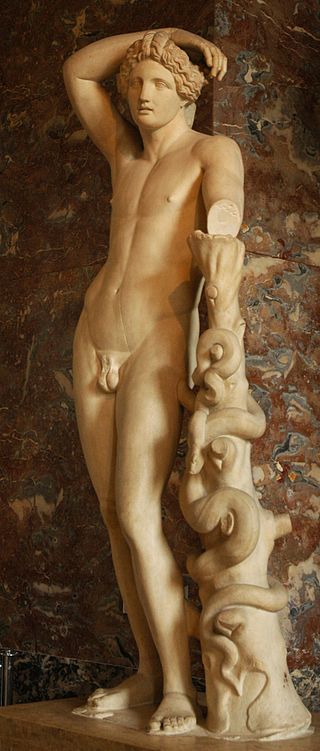

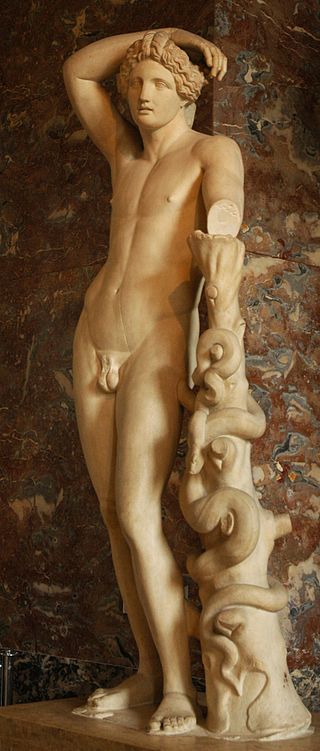

The Apollo Lyceus type, also known as Lycean Apollo, originating with Praxiteles and known from many full-size statue and figurine copies as well as from 1st century BCE Athenian coinage, is a statue type of Apollo showing the god resting on a support, his right forearm touching the top of his head and his hair fixed in braids on the top of a head in a haircut typical of childhood. It is called "Lycean" not after Lycia itself, but after its identification with a lost work described, though not attributed to a sculptor, by Lucian as being on show in the Lyceum, one of the gymnasia of Athens. According to Lucian, the god leaning on a support with his bow in his left hand and his right resting on his head is shown "as if resting after long effort." Its main exemplar is the Apollino in Florence or Apollo Medici, in the Uffizi, Florence.

Lysippos was a Greek sculptor of the 4th century BC. Together with Scopas and Praxiteles, he is considered one of the three greatest sculptors of the Classical Greek era, bringing transition into the Hellenistic period. Problems confront the study of Lysippos because of the difficulty of identifying his style among the copies which survive. Not only did he have a large workshop and many disciples in his immediate circle, but there is understood to have been a market for replicas of his work, supplied from outside his circle, both in his lifetime and later in the Hellenistic and Roman periods. The Victorious Youth or Getty bronze, which resurfaced around 1972, has been associated with him.

Scopas was an ancient Greek sculptor and architect, most famous for his statue of Meleager, the copper statue of Aphrodite, and the head of goddess Hygieia, daughter of Asclepius.

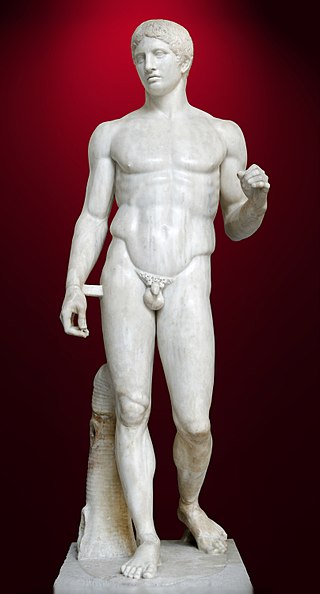

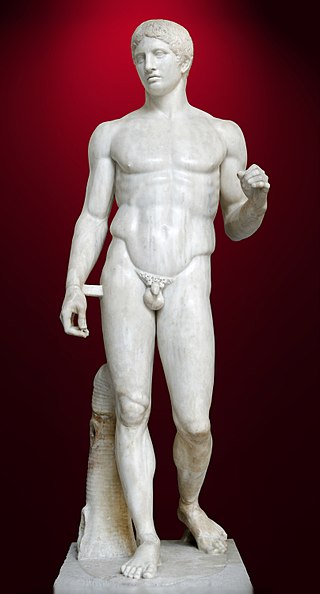

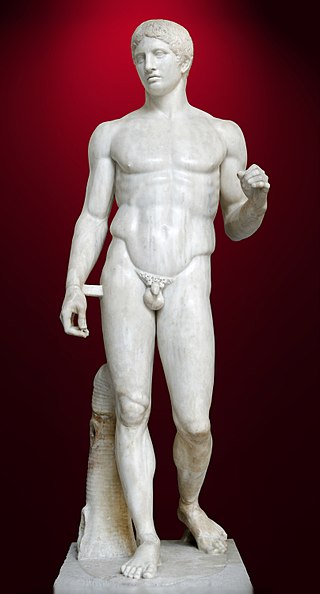

The Doryphoros of Polykleitos is one of the best known Greek sculptures of Classical antiquity, depicting a solidly built, muscular, standing warrior, originally bearing a spear balanced on his left shoulder. Rendered somewhat above life-size, the lost bronze original of the work would have been cast circa 440 BC, but it is today known only from later marble copies. The work nonetheless forms an important early example of both Classical Greek contrapposto and classical realism; as such, the iconic Doryphoros proved highly influential elsewhere in ancient art.

The sculpture of ancient Greece is the main surviving type of fine ancient Greek art as, with the exception of painted ancient Greek pottery, almost no ancient Greek painting survives. Modern scholarship identifies three major stages in monumental sculpture in bronze and stone: the Archaic, Classical (480–323) and Hellenistic. At all periods there were great numbers of Greek terracotta figurines and small sculptures in metal and other materials.

Cephisodotus or Kephisodotos was a Greek sculptor, perhaps the father or an uncle of Praxiteles, one of whose sculptor sons was Cephisodotus the Younger.

The Diadumenos ("diadem-bearer"), together with the Doryphoros, are two of the most famous figural types of the sculptor Polyclitus, forming a basic pattern of Ancient Greek sculpture that all present strictly idealized representations of young male athletes in a convincingly naturalistic manner.

The Aphrodite of Knidos was an Ancient Greek sculpture of the goddess Aphrodite created by Praxiteles of Athens around the 4th century BC. It was one of the first life-sized representations of the nude female form in Greek history, displaying an alternative idea to male heroic nudity. Praxiteles' Aphrodite was shown nude, reaching for a bath towel while covering her pubis, which, in turn leaves her breasts exposed. Up until this point, Greek sculpture had been dominated by male nude figures. The original Greek sculpture is no longer in existence; however, many Roman copies survive of this influential work of art. Variants of the Venus Pudica are the Venus de' Medici and the Capitoline Venus.

Classical sculpture refers generally to sculpture from Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome, as well as the Hellenized and Romanized civilizations under their rule or influence, from about 500 BC to around 200 AD. It may also refer more precisely a period within Ancient Greek sculpture from around 500 BC to the onset of the Hellenistic style around 323 BC, in this case usually given a capital "C". The term "classical" is also widely used for a stylistic tendency in later sculpture, not restricted to works in a Neoclassical or classical style.

Apoxyomenos is one of the conventional subjects of ancient Greek votive sculpture; it represents an athlete, caught in the familiar act of scraping sweat and dust from his body with the small curved instrument that the Greeks called a stlengis and the Romans a strigil.

The Antikythera Ephebe, registered as: Bronze statue of a youth in the museum collections, is a bronze statue of a young man of languorous grace that was found in 1900 by sponge-divers in the area of the ancient Antikythera shipwreck off the island of Antikythera, Greece. It was the first of the series of Greek bronze sculptures that the Aegean and Mediterranean yielded up in the twentieth century which have fundamentally altered the modern view of ancient Greek sculpture. The wreck site, which is dated about 70–60 BC, also yielded the Antikythera mechanism, a characterful head of a Stoic philosopher, and a hoard of coins. The coins included a disproportionate quantity of Pergamene cistophoric tetradrachms and Ephesian coins, leading scholars to surmise that it had begun its journey on the Ionian coast, perhaps at Ephesus; none of its recovered cargo has been identified as from mainland Greece.

The Hermes of the Museo Pio-Clementino is an ancient Roman sculpture, part of the Vatican collections, Rome. It was long admired as the Belvedere Antinous, named from its prominent placement in the Cortile del Belvedere. It is now inventory number 907 in the Museo Pio-Clementino.

Apollo Sauroktonos is the title of several 1st – 2nd century AD Roman marble copies of an original by the ancient Greek sculptor Praxiteles. The statues depict a nude adolescent Apollo about to catch a lizard climbing up a tree. Copies are included in the collections of the Louvre Museum, the Vatican Museums, and the National Museums Liverpool.

Pliny the Elder records five bronze statues of Amazons in the Artemision of Ephesus. He explains the existence of such a quantity of sculptures on the same theme in the same place by describing a 5th-century BC competition between the artists Polyclitus, Phidias, Kresilas, "Kydon" and Phradmon; thus:

The most celebrated of these artists, though born at different epochs, have joined in a trial of skill in the Amazons which they have respectively made. When these statues were dedicated in the Temple of Diana at Ephesus, it was agreed, in order to ascertain which was the best, that it should be left to the judgment of the artists themselves who were then present: upon which, it was evident that that was the best, which all the artists agreed in considering as the next best to his own. Accordingly, the first rank was assigned to Polycletus, the second to Phidias, the third to Cresilas, the fourth to Cydon, and the fifth to Phradmon.

The Resting Satyr or Leaning Satyr, also known as the Satyr anapauomenos is a statue type generally attributed to the ancient Greek sculptor Praxiteles. Some 115 examples of the type are known, of which the best known is in the Capitoline Museums.

The Lansdowne Heracles is a Roman marble sculpture of about 125 CE. Today it is in the collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum's Getty Villa on the Malibu Coast, Los Angeles. The statue represents the hero Heracles as a beardless Lysippic youth grasping the skin of the Nemean lion with his club upon his shoulder. The work was discovered in 1790 in Tivoli, Italy, on the site of Hadrian's Villa, where many fine Hadrianic copies and pastiches of Greek sculptures had been discovered since the 16th century. Today, the sculpture is considered to be an example of Roman-era improvisations on the Greek sculptural style of the fourth century BCE rather than a copy of a specific Greek original.

Antoine-Félix Bouré, known in his own time as Félix Bouré but sometimes found in modern scholarship as Antoine Bouré, was a Belgian sculptor, best known for his monumental lions.