Related Research Articles

A head injury is any injury that results in trauma to the skull or brain. The terms traumatic brain injury and head injury are often used interchangeably in the medical literature. Because head injuries cover such a broad scope of injuries, there are many causes—including accidents, falls, physical assault, or traffic accidents—that can cause head injuries.

Neurotrauma, brain damage or brain injury (BI) is the destruction or degeneration of brain cells. Brain injuries occur due to a wide range of internal and external factors. In general, brain damage refers to significant, undiscriminating trauma-induced damage.

Rehabilitation of sensory and cognitive function typically involves methods for retraining neural pathways or training new neural pathways to regain or improve neurocognitive functioning that have been diminished by disease or trauma. The main objective outcome for rehabilitation is to assist in regaining physical abilities and improving performance. Three common neuropsychological problems treatable with rehabilitation are attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), concussion, and spinal cord injury. Rehabilitation research and practices are a fertile area for clinical neuropsychologists, rehabilitation psychologists, and others.

A concussion, also known as a mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), is a head injury that temporarily affects brain functioning. Symptoms may include loss of consciousness; memory loss; headaches; difficulty with thinking, concentration, or balance; nausea; blurred vision; dizziness; sleep disturbances, and mood changes. Any of these symptoms may begin immediately, or appear days after the injury. Concussion should be suspected if a person indirectly or directly hits their head and experiences any of the symptoms of concussion. Symptoms of a concussion may be delayed by 1-2 days after the accident. It is not unusual for symptoms to last 2 weeks in adults and 4 weeks in children. Fewer than 10% of sports-related concussions among children are associated with loss of consciousness.

A subdural hematoma (SDH) is a type of bleeding in which a collection of blood—usually but not always associated with a traumatic brain injury—gathers between the inner layer of the dura mater and the arachnoid mater of the meninges surrounding the brain. It usually results from tears in bridging veins that cross the subdural space.

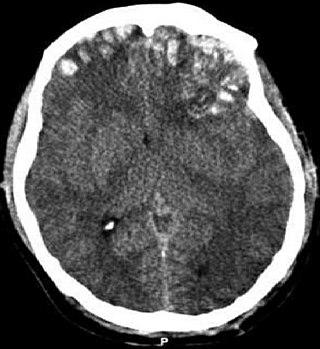

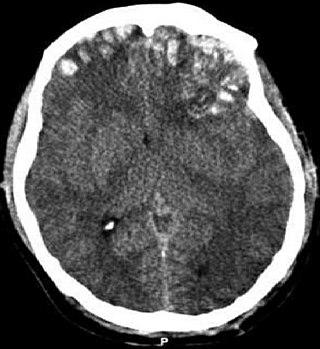

Intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), also known as intracranial bleed, is bleeding within the skull. Subtypes are intracerebral bleeds, subarachnoid bleeds, epidural bleeds, and subdural bleeds. More often than not it ends in a lethal outcome.

A traumatic brain injury (TBI), also known as an intracranial injury, is an injury to the brain caused by an external force. TBI can be classified based on severity, mechanism, or other features. Head injury is a broader category that may involve damage to other structures such as the scalp and skull. TBI can result in physical, cognitive, social, emotional and behavioral symptoms, and outcomes can range from complete recovery to permanent disability or death.

Cerebral contusion, Latin contusio cerebri, a form of traumatic brain injury, is a bruise of the brain tissue. Like bruises in other tissues, cerebral contusion can be associated with multiple microhemorrhages, small blood vessel leaks into brain tissue. Contusion occurs in 20–30% of severe head injuries. A cerebral laceration is a similar injury except that, according to their respective definitions, the pia-arachnoid membranes are torn over the site of injury in laceration and are not torn in contusion. The injury can cause a decline in mental function in the long term and in the emergency setting may result in brain herniation, a life-threatening condition in which parts of the brain are squeezed past parts of the skull. Thus treatment aims to prevent dangerous rises in intracranial pressure, the pressure within the skull.

Post-concussion syndrome (PCS), also known as persisting symptoms after concussion, is a set of symptoms that may continue for weeks, months, years after a concussion. PCS is medically classified as a mild traumatic brain injury (TBI). About 35% of people with concussion experience persistent or prolonged symptoms 3 to 6 months after injury. Prolonged concussion is defined as having concussion symptoms for over four weeks following the first accident in youth and for weeks or months in adults.

Blunt trauma, also known as blunt force trauma or non-penetrating trauma, is physical trauma or impactful force to a body part, often occurring with road traffic collisions, direct blows, assaults, injuries during sports, and particularly in the elderly who fall. It is contrasted with penetrating trauma which occurs when an object pierces the skin and enters a tissue of the body, creating an open wound and bruise.

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) is a neurodegenerative disease linked to repeated trauma to the head. The encephalopathy symptoms can include behavioral problems, mood problems, and problems with thinking. The disease often gets worse over time and can result in dementia. It is unclear if the risk of suicide is altered.

Second-impact syndrome (SIS) occurs when the brain swells rapidly, and catastrophically, after a person has a second concussion before symptoms from an earlier one have subsided. This second blow may occur minutes, days, or weeks after an initial concussion, and even the mildest grade of concussion can lead to second impact syndrome. The condition is often fatal, and almost everyone who is not killed is severely disabled. The cause of SIS is uncertain, but it is thought that the brain's arterioles lose their ability to regulate their diameter, and therefore lose control over cerebral blood flow, causing massive cerebral edema.

Post-traumatic amnesia (PTA) is a state of confusion that occurs immediately following a traumatic brain injury (TBI) in which the injured person is disoriented and unable to remember events that occur after the injury. The person may be unable to state their name, where they are, and what time it is. When continuous memory returns, PTA is considered to have resolved. While PTA lasts, new events cannot be stored in the memory. About a third of patients with mild head injury are reported to have "islands of memory", in which the patient can recall only some events. During PTA, the patient's consciousness is "clouded". Because PTA involves confusion in addition to the memory loss typical of amnesia, the term "post-traumatic confusional state" has been proposed as an alternative.

Post-traumatic seizures (PTS) are seizures that result from traumatic brain injury (TBI), brain damage caused by physical trauma. PTS may be a risk factor for post-traumatic epilepsy (PTE), but a person having a seizure or seizures due to traumatic brain injury does not necessarily have PTE, which is a form of epilepsy, a chronic condition in which seizures occur repeatedly. However, "PTS" and "PTE" may be used interchangeably in medical literature.

The Rivermead Post-Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire, abbreviated RPQ, is a questionnaire that can be administered to someone who sustains a concussion or other form of traumatic brain injury to measure the severity of symptoms. The RPQ is used to determine the presence and severity of post-concussion syndrome (PCS), a set of somatic, cognitive, and emotional symptoms following traumatic brain injury that may persist anywhere from a week, to months, or even more than six months.

Traumatic brain injury can cause a variety of complications, health effects that are not TBI themselves but that result from it. The risk of complications increases with the severity of the trauma; however even mild traumatic brain injury can result in disabilities that interfere with social interactions, employment, and everyday living. TBI can cause a variety of problems including physical, cognitive, emotional, and behavioral complications.

Prevention of mild traumatic brain injury involves taking general measures to prevent traumatic brain injury, such as wearing seat belts, using airbags in cars, securing heavy furnitures and objects before earthquake or covering and holding under the table during an earthquake. Older people are encouraged to try to prevent falls, for example by keeping floors free of clutter and wearing thin, flat, shoes with hard soles that do not interfere with balance.

A sports-related traumatic brain injury is a serious accident which may lead to significant morbidity or mortality. Traumatic brain injury (TBI) in sports are usually a result of physical contact with another person or stationary object, These sports may include boxing, gridiron football, field/ice hockey, lacrosse, martial arts, rugby, soccer, wrestling, auto racing, cycling, equestrian, rollerblading, skateboarding, skiing or snowboarding.

Sleep disorder is a common repercussion of traumatic brain injury (TBI). It occurs in 30%-70% of patients with TBI. TBI can be distinguished into two categories, primary and secondary damage. Primary damage includes injuries of white matter, focal contusion, cerebral edema and hematomas, mostly occurring at the moment of the trauma. Secondary damage involves the damage of neurotransmitter release, inflammatory responses, mitochondrial dysfunctions and gene activation, occurring minutes to days following the trauma. Patients with sleeping disorders following TBI specifically develop insomnia, sleep apnea, narcolepsy, periodic limb movement disorder and hypersomnia. Furthermore, circadian sleep-wake disorders can occur after TBI.

A pediatric concussion, also known as pediatric mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), is a head trauma that impacts the brain capacity. Concussion can affect functional, emotional, cognitive and physical factors and can occur in people of all ages. Symptoms following after the concussion vary and may include confusion, disorientation, lightheadedness, nausea, vomiting, blurred vision, loss of consciousness (LOC) and environment sensitivity. Concussion symptoms may vary based on the type, severity and location of the head injury. Concussion symptoms in infants, children, and adolescents often appear immediately after the injury, however, some symptoms may arise multiple days following the injury leading to a concussion. The majority of pediatric patients recover from the symptoms within one month following the injury. 10-30% of children and adolescents have a higher risk of a delayed recovery or of experiencing concussion symptoms that persist.

References

- 1 2 Ibrahim, Nicole G.; Ralston, Jill; Smith, Colin; Margulies, Susan S. (2010). "Physiological and Pathological Responses to Head Rotations in Toddler Piglets". Journal of Neurotrauma. 27 (6): 1021–35. doi:10.1089/neu.2009.1212. PMC 2943503 . PMID 20560753.

- ↑ Cossa, F.M.; Fabiani, M. (1999). "Attention in closed head injury: a critical review". The Italian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 20 (3): 145–53. doi:10.1007/s100720050024. PMID 10541596. S2CID 25139526.

- 1 2 3 4 Faul, Mark; Xu, Likang; Wald, Marlena M.; Coronado, Victor G. (2010). "Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations and Deaths 2002-2006". National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

- 1 2 Nih Consensus Development Panel On Rehabilitation Of Persons With Traumatic Brain Injury (1999). "Consensus conference. Rehabilitation of persons with traumatic brain injury. NIH Consensus Development Panel on Rehabilitation of Persons With Traumatic Brain Injury". JAMA. 282 (10): 974–83. doi:10.1001/jama.282.10.974. PMID 10485684.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 http://www.allabouttbi.com/symptoms.htm%5B%5D%5B%5D

- ↑ Rao, Vani; Lyketsos, Constantine G. (2003). "Editorial Psychiatric aspects of traumatic brain injury: new solutions to an old problem". International Review of Psychiatry . 15 (4): 299–301. doi:10.1080/09540260310001606674. S2CID 145239608.

- ↑ Koponen, Salla; Taiminen, Tero; Portin, Raija; Himanen, Leena; Isoniemi, Heli; Heinonen, Hanna; Hinkka, Susanna; Tenovuo, Olli (2002). "Axis I and II Psychiatric Disorders After Traumatic Brain Injury: A 30-Year Follow-Up Study". American Journal of Psychiatry. 159 (8): 1315–21. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.8.1315. PMID 12153823. S2CID 18676013.

- ↑ Kissinger, Daniel B. (2008). "Traumatic brain injury and employment outcomes: integration of the working alliance model". Work. 31 (3): 309–17. PMID 19029672.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) (1997). "Sports-Related Recurrent Brain Injuries -- United States". MMWR. 46 (10): 224–7. PMID 9082176.

- ↑ Taber, K. H.; Warden, D. L.; Hurley, R. A. (2006). "Blast-Related Traumatic Brain Injury: What Is Known?". Journal of Neuropsychiatry. 18 (2): 141–5. doi:10.1176/jnp.2006.18.2.141. PMID 16720789.

- ↑ Vasterling, Jennifer J.; Verfaellie, Mieke; Sullivan, Karen D. (2009). "Mild traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder in returning veterans: Perspectives from cognitive neuroscience". Clinical Psychology Review. 29 (8): 674–84. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.08.004. PMID 19744760.

- ↑ Morrow, Stephen E.; Pearson, Matthew (2010). "Management Strategies for Severe Closed Head Injuries in Children". Seminars in Pediatric Surgery. 19 (4): 279–85. doi:10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2010.07.001. PMID 20889084.

- ↑ Gotschall, Catherine S.; Papero, Patricia H.; Snyder, Heather M.; Johnson, Dennis L.; Sacco, William J.; Eichelberger, Martin R. (1995). "Comparison of Three Measures of Injury Severity in Children with Traumatic Brain Injury". Journal of Neurotrauma. 12 (4): 611–9. doi:10.1089/neu.1995.12.611. PMID 8683612.

- ↑ Maas, Andrew IR; Stocchetti, Nino; Bullock, Ross (2008). "Moderate and severe traumatic brain injury in adults". The Lancet Neurology. 7 (8): 728–41. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70164-9. PMID 18635021. S2CID 14071224.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Comper, P.; Bisschop, S. M.; Carnide, N.; Tricco, A. (2005). "A systematic review of treatments for mild traumatic brain injury". Brain Injury. 19 (11): 863–80. doi:10.1080/02699050400025042. PMID 16296570. S2CID 34912966.

- ↑ Interview with Dr. Anthony Stringer, Emory University, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine[ verification needed ]

- ↑ "Progesterone for traumatic brain injury tested in phase III clinical trial" (Press release). Emory University. February 22, 2010. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ↑ http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2004/WHO_DAR_01.9_eng.pdf%5B%5D%5B%5D

- ↑ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia : Head injury - first aid

- ↑ Albergotti, Reed; Wang, Shirley S. (11 November 2009). "Is It Time to Retire the Football Helmet?". The Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ "CDC | Traumatic Brain Injury | Injury Center".

- ↑ Sandel, M.Elizabeth; Bell, Kathleen R.; Michaud, Linda J. (1998). "Traumatic brain injury: Prevention, pathophysiology, and outcome prediction". Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 79 (3): S3–S9. doi:10.1016/S0003-9993(98)90113-7. INIST:2242542.

- ↑ http://www.cyclehelmets.org/1041.html%5B%5D%5B%5D

- ↑ Robinson, D.L. (1996). "Head injuries and bicycle helmet laws". Accident Analysis & Prevention. 28 (4): 463–75. doi:10.1016/0001-4575(96)00016-4. PMID 8870773.

- ↑ Rosenkranz, Kari M.; Sheridan, Robert L. (2003). "Trauma to adult bicyclists: a growing problem in the urban environment". Injury. 34 (11): 825–9. doi:10.1016/S0020-1383(02)00389-3. PMID 14580814.

- ↑ "NSAA : National Ski Areas Association : Press". Archived from the original on 2007-02-08. Retrieved 2011-09-24.[ full citation needed ]

- ↑ http://casr.adelaide.edu.au/developments/headband/%5B%5D%5B%5D