Catatonia is a complex neuropsychiatric behavioral syndrome that is characterized by abnormal movements, immobility, abnormal behaviors, and withdrawal. The onset of catatonia can be acute or subtle and symptoms can wax, wane, or change during episodes. It has historically been related to schizophrenia, but catatonia is most often seen in mood disorders. It is now known that catatonic symptoms are nonspecific and may be observed in other mental, neurological, and medical conditions. Catatonia is now a stand-alone diagnosis, and the term is used to describe a feature of the underlying disorder.

Delirium is a specific state of acute confusion attributable to the direct physiological consequence of a medical condition, effects of a psychoactive substance, or multiple causes, which usually develops over the course of hours to days. As a syndrome, delirium presents with disturbances in attention, awareness, and higher-order cognition. People with delirium may experience other neuropsychiatric disturbances, including changes in psychomotor activity, disrupted sleep-wake cycle, emotional disturbances, disturbances of consciousness, or, altered state of consciousness, as well as perceptual disturbances, although these features are not required for diagnosis.

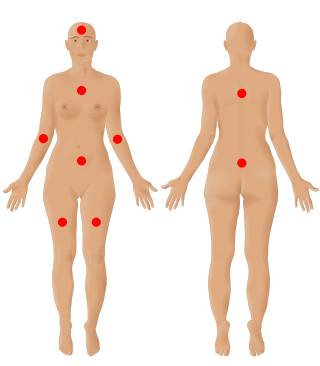

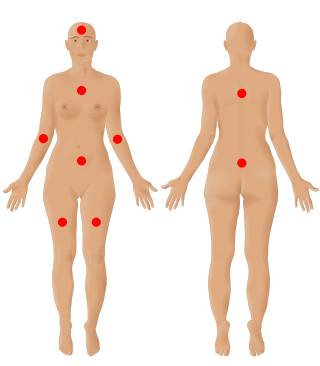

Fibromyalgia is a medical condition which causes chronic widespread pain, accompanied by fatigue, waking unrefreshed and cognitive symptoms. Other symptoms include headaches, lower abdominal pain or cramps, and depression. People with fibromyalgia can also experience insomnia and a general hypersensitivity.

Somatization disorder was a mental and behavioral disorder characterized by recurring, multiple, and current, clinically significant complaints about somatic symptoms. It was recognized in the DSM-IV-TR classification system, but in the latest version DSM-5, it was combined with undifferentiated somatoform disorder to become somatic symptom disorder, a diagnosis which no longer requires a specific number of somatic symptoms. ICD-10, the latest version of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, still includes somatization syndrome.

Hypersomnia is a neurological disorder of excessive time spent sleeping or excessive sleepiness. It can have many possible causes and can cause distress and problems with functioning. In the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), hypersomnolence, of which there are several subtypes, appears under sleep-wake disorders.

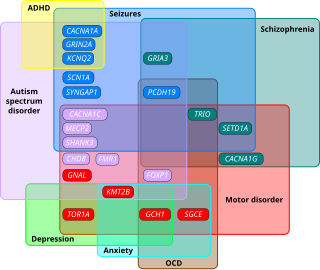

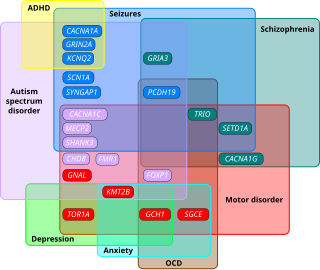

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are neurodevelopmental disorders that begin in early childhood, persist throughout adulthood, and affect three crucial areas of development: communication, social interaction and restricted patterns of behavior. There are many conditions comorbid to autism spectrum disorders such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and epilepsy.

Cognitive disorders (CDs), also known as neurocognitive disorders (NCDs), are a category of mental health disorders that primarily affect cognitive abilities including learning, memory, perception, and problem-solving. Neurocognitive disorders include delirium, mild neurocognitive disorders, and major neurocognitive disorder. They are defined by deficits in cognitive ability that are acquired, typically represent decline, and may have an underlying brain pathology. The DSM-5 defines six key domains of cognitive function: executive function, learning and memory, perceptual-motor function, language, complex attention, and social cognition.

Cognitive disengagement syndrome (CDS) is an attention syndrome characterised by prominent dreaminess, mental fogginess, hypoactivity, sluggishness, slow reaction time, staring frequently, inconsistent alertness, and a slow working speed. To scientists in the field, it has reached the threshold of evidence and recognition as a distinct syndrome.

Post-concussion syndrome (PCS), also known as persisting symptoms after concussion, is a set of symptoms that may continue for weeks, months, or years after a concussion. PCS is medically classified as a mild traumatic brain injury (TBI). About 35% of people with concussion experience persistent or prolonged symptoms 3 to 6 months after injury. Prolonged concussion is defined as having concussion symptoms for over four weeks following the first accident in youth and for weeks or months in adults.

Frontal lobe disorder, also frontal lobe syndrome, is an impairment of the frontal lobe of the brain due to disease or frontal lobe injury. The frontal lobe plays a key role in executive functions such as motivation, planning, social behaviour, and speech production. Frontal lobe syndrome can be caused by a range of conditions including head trauma, tumours, neurodegenerative diseases, neurodevelopmental disorders, neurosurgery and cerebrovascular disease. Frontal lobe impairment can be detected by recognition of typical signs and symptoms, use of simple screening tests, and specialist neurological testing.

Organic brain syndrome, also known as organic brain disease, organic brain damage, organic brain disorder, organic mental syndrome, or organic mental disorder, refers to any syndrome or disorder of mental function whose cause is alleged to be known as organic (physiologic) rather than purely of the mind. These names are older and nearly obsolete general terms from psychiatry, referring to many physical disorders that cause impaired mental function. They are meant to exclude psychiatric disorders. Originally, the term was created to distinguish physical causes of mental impairment from psychiatric disorders, but during the era when this distinction was drawn, not enough was known about brain science for this cause-based classification to be more than educated guesswork labeled with misplaced certainty, which is why it has been deemphasized in current medicine. While mental or behavioural abnormalities related to the dysfunction can be permanent, treating the disease early may prevent permanent damage in addition to fully restoring mental functions. An organic cause to brain dysfunction is suspected when there is no indication of a clearly defined psychiatric or "inorganic" cause, such as a mood disorder.

Medically unexplained physical symptoms are symptoms for which a treating physician or other healthcare providers have found no medical cause, or whose cause remains contested. In its strictest sense, the term simply means that the cause for the symptoms is unknown or disputed—there is no scientific consensus. Not all medically unexplained symptoms are influenced by identifiable psychological factors. However, in practice, most physicians and authors who use the term consider that the symptoms most likely arise from psychological causes. Typically, the possibility that MUPS are caused by prescription drugs or other drugs is ignored. It is estimated that between 15% and 30% of all primary care consultations are for medically unexplained symptoms. A large Canadian community survey revealed that the most common medically unexplained symptoms are musculoskeletal pain, ear, nose, and throat symptoms, abdominal pain and gastrointestinal symptoms, fatigue, and dizziness. The term MUPS can also be used to refer to syndromes whose etiology remains contested, including chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, multiple chemical sensitivity and Gulf War illness.

Oneiroid syndrome (OS) is a condition involving dream-like disturbances of one's consciousness by vivid scenic hallucinations, accompanied by catatonic symptoms (either catatonic stupor or excitement), delusions, or psychopathological experiences of a kaleidoscopic nature. The term is from Ancient Greek "ὄνειρος" (óneiros, meaning "dream") and "εἶδος" (eîdos, meaning "form, likeness"; literally dream-like / oneiric or oniric, sometimes called "nightmare-like"). It is a common complication of catatonic schizophrenia, although it can also be caused by other mental disorders. The dream-like experiences are vivid enough to seem real to the patient. OS is distinguished from delirium by the fact that the imaginative experiences of patients always have an internal projection. This syndrome is hardly mentioned in standard psychiatric textbooks, possibly because it is not listed in DSM.

Alcohol-related dementia (ARD) is a form of dementia caused by long-term, excessive consumption of alcohol, resulting in neurological damage and impaired cognitive function.

Pseudodementia is a condition where mental cognition can be temporarily decreased. The term pseudodementia is applied to the range of functional psychiatric conditions such as depression, schizophrenia and other psychosis, mania, dissociative disorder and conversion disorder that may mimic organic dementia, but are essentially reversible on treatment. Pseudodementia typically involves three cognitive components: memory issues, deficits in executive functioning, and deficits in speech and language. Specific cognitive symptoms might include trouble recalling words or remembering things in general, decreased attentional control and concentration, difficulty completing tasks or making decisions, decreased speed and fluency of speech, and impaired processing speed. People with pseudodementia are typically very distressed about the cognitive impairment they experience. Two treatments found to be effective for the treatment of depression may also be beneficial in the treatment of pseudodementia: Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) which identifies behaviors that positively and negatively impact mood, and Interpersonal therapy which focuses on identifying ways in which interpersonal relationships contribute to depression.

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS) is a set of symptoms that can occur following a reduction in alcohol use after a period of excessive use. Symptoms typically include anxiety, shakiness, sweating, vomiting, fast heart rate, and a mild fever. More severe symptoms may include seizures, and delirium tremens (DTs); which can be fatal in untreated patients. Symptoms start at around 6 hours after last drink. Peak incidence of seizures occurs at 24-36 hours and peak incidence of delirium tremens is at 48-72 hours.

A neurological disorder is any disorder of the nervous system. Structural, biochemical or electrical abnormalities in the brain, spinal cord or other nerves can result in a range of symptoms. Examples of symptoms include paralysis, muscle weakness, poor coordination, loss of sensation, seizures, confusion, pain, tauopathies, and altered levels of consciousness. There are many recognized neurological disorders, some relatively common, but many rare. They may be assessed by neurological examination, and studied and treated within the specialties of neurology and clinical neuropsychology.

Functional disorders are a group of recognisable medical conditions which are due to changes to the functioning of the systems of the body rather than due to a disease affecting the structure of the body.

Somatic symptom disorder, also known as somatoform disorder, is defined by one or more chronic physical symptoms that coincide with excessive and maladaptive thoughts, emotions, and behaviors connected to those symptoms. The symptoms are not deliberately produced or feigned, and they may or may not coexist with a known medical ailment.

The term functional somatic syndrome (FSS) refers to a group of chronic diagnoses with no identifiable organic cause. This term was coined by Hemanth Samkumar. It encompasses disorders such as chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, chronic widespread pain, temporomandibular disorder, irritable bowel syndrome, lower back pain, tension headache, atypical face pain, non-cardiac chest pain, insomnia, palpitation, dyspepsia and dizziness. General overlap exists between this term, somatization and somatoform.