The Battle of Cape Palos, also known as the Second Battle of Cape Palos, was the biggest naval battle of the Spanish Civil War, fought on the night of March 5–6, 1938, east of Cape Palos near Cartagena, Spain.

The blazon of the coat of arms of the Princess of Asturias is given by a Royal Decree 979 on 30 October 2015 which was an amendment of the Royal Decree 1511 dated Madrid 21 January 1977, which also created her guidon and her standard.

The Coat of arms of Peru is the national symbolic emblem of Peru. Four variants are used: the Coat of arms per se ; the National Coat of arms, or National Shield ; the Great Seal of the State ; and the Naval Coat of arms.

The current Basque coat of arms is the official coat of arms of the Basque Country, Autonomous community of Spain. It consists of a party per cross representing the three historical territories of Álava, Gipuzkoa and Biscay, as well as a fourth, void quarter. The arms are ringed by a regal wreath of oak leaves, symbolic of the Gernikako Arbola. The fourth quarter constituted since the late 19th century the linked chains of Navarre; however, following a legal suit by the Navarre Government claiming that the usage of the arms of a region on the flag of another was illegal, the Constitutional Court of Spain ordered the removal of the chains of Navarre in a judgement of 1986.

The bear as heraldic charge is not as widely used as the lion, boar or other beasts.

The Coat of arms of Balearic Islands is described in the Spanish Law 7 of November 21, 1984, the Law of the coat of arms of the Autonomous Community of Balearic Islands. Previously, by Decree of the Interinsular General Council of August 7 and 16, 1978, adopted the coat of arms as official symbol of the Balearic Islands.

The coat of arms of the Extremadura is described in the Title I of the Spanish Law 4 of June 3, 1985, the Law of the coat of arms, flag and regional day of Extremadura.

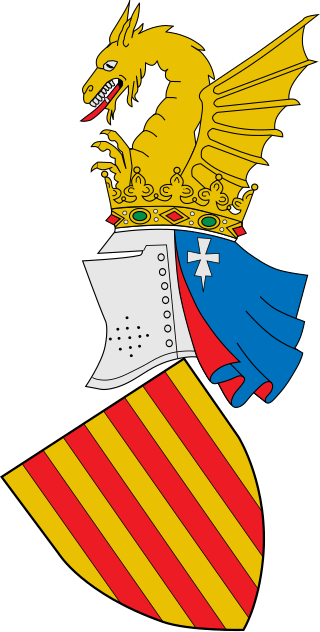

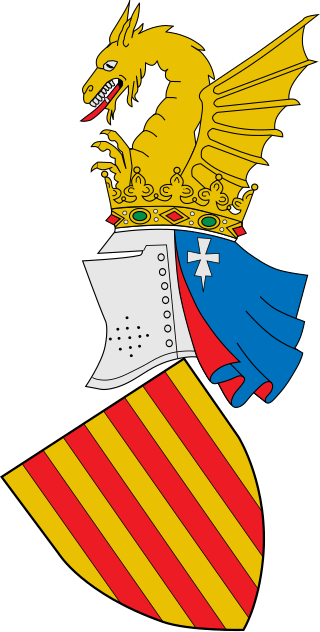

The coat of arms of the Valencian Community is the official emblem of the self-government institutions of the Valencian Community. It is based on the armorial achievement used from the reign of King Peter IV to John II, called the Great. In 1978 the former Council of the Valencian Country approved it “...for being the oldest known representative emblem of the former Kingdom of Valencia, that had located on the Xerea Gate of the city of Valencia”.

The so-called Bars of Aragon, Royal sign of Aragon, Royal arms of Aragon, Four Bars, Red Bars or Coat of arms of the Crown of Aragon, which bear four red pallets on gold background, depicts the familiar coat of the Kings of Aragon. It differs from the flag because this latter instead uses bars. It is one of the oldest coats of arms in Europe dating back to a seal of Raymond Berengar IV, Count of Barcelona and Prince of Aragon, from 1150.

Sánchez Barcáiztegui was a Churruca-class destroyer of the Spanish Republican Navy. She took part in the Spanish Civil War on the side of the government of the Second Spanish Republic.

Lepanto was a Churruca-class destroyer of the Spanish Republican Navy. She took part in the Spanish Civil War on the side of the government of the Second Spanish Republic. She was named after the Battle of Lepanto.

The coat of arms of Toledo may refer to the City of Toledo and for the Province of Toledo.

The Coat of arms of the Second Spanish Republic was the emblem of the Second Spanish Republic, the government that existed in Spain between April 14, 1931, when King Alfonso XIII left the country, and April 1, 1939, when the last of the Republican forces surrendered to Francoist forces at the end of the Spanish Civil War.

The Spanish monarchs of the House of Habsburg and Philip V used separate versions of their royal arms as sovereigns of the Kingdom of Naples-Sicily, Sardinia and the Duchy of Milan with the arms of these territories.

The Laureate Badge of Madrid was the highest military award for gallantry of the Second Spanish Republic. It was awarded in recognition of action, either individual or collective, to protect the nation and its citizens in the face of immediate risk to the bearer or bearers' life. Those eligible were members of the Spanish Republican Armed Forces and testimonies of reliable witnesses were checked prior to concession.

Luis González de Ubieta y González del Campillo was an admiral of the Spanish Republican Navy during the Spanish Civil War. He died in exile as the captain of the Panamanian merchant vessel Chiriqui, refusing to be rescued when the ship under his command sank in the Caribbean Sea not far from Barranquilla.

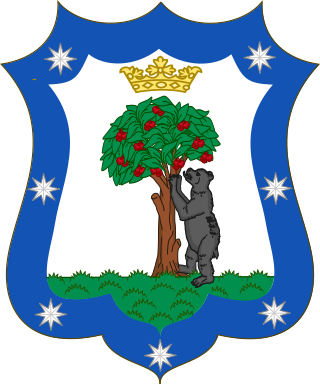

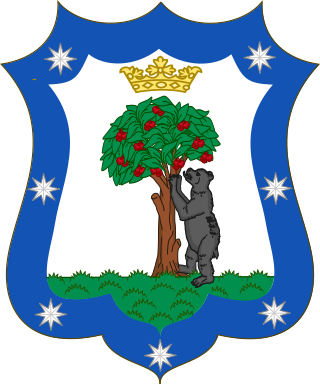

The Statue of the Bear and the Strawberry Tree is a sculpture from the second half of the 20th century, situated in the Spanish city of Madrid. It represents the coat of arms of Madrid and is found on the east side of the Puerta del Sol, between Calle de Alcalá and Carrera de San Jerónimo, in the historical centre of the capital.

The Madrid Distinction was one of the highest military awards of the Second Spanish Republic. It was a decoration related to the Laureate Plate of Madrid. which was established by the Second Spanish Republic in order to reward courage. In the same manner as the Laureate Plate it was named after Madrid, the capital of Spain, owing to the city symbolizing valour and the defence of the Spanish Republic during the long Siege of Madrid throughout the Spanish Civil War.

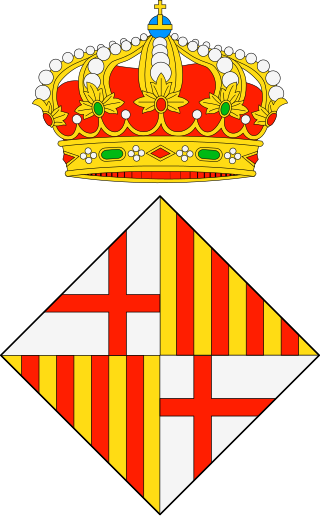

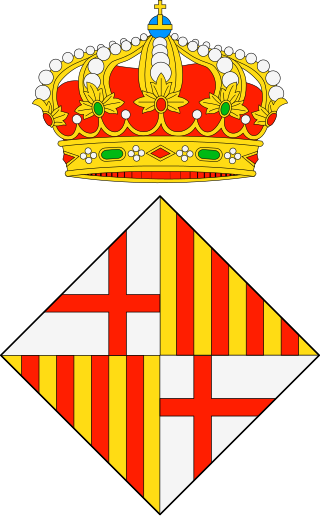

The coat of arms of Barcelona is the official emblem of the City Council of Barcelona, the capital of Catalonia, has its origin in the Middle Ages, these arms were first documented in 1329. The Government of Catalonia conferred the coat of arms and the flag as official symbols of the municipality in 2004. It has an escutcheon in lozenge which is commonly used in municipal coats of arms of cities in Catalonia. Currently the City Council of Barcelona also uses an isotype based on the heraldry of the city.

The coat of arms of Castile was the heraldic emblem of its monarchs. Historian Michel Pastoureau says that the original purpose of heraldic emblems and seals was to facilitate the exercise of power and the identification of the ruler, due to what they offered for achieving these aims. These symbols were associated with the kingdom, and eventually also represented the intangible nature of the national sentiment or sense of belonging to a territory.