Related Research Articles

Cognitive science is the interdisciplinary, scientific study of the mind and its processes with input from linguistics, psychology, neuroscience, philosophy, computer science/artificial intelligence, and anthropology. It examines the nature, the tasks, and the functions of cognition. Cognitive scientists study intelligence and behavior, with a focus on how nervous systems represent, process, and transform information. Mental faculties of concern to cognitive scientists include language, perception, memory, attention, reasoning, and emotion; to understand these faculties, cognitive scientists borrow from fields such as linguistics, psychology, artificial intelligence, philosophy, neuroscience, and anthropology. The typical analysis of cognitive science spans many levels of organization, from learning and decision to logic and planning; from neural circuitry to modular brain organization. One of the fundamental concepts of cognitive science is that "thinking can best be understood in terms of representational structures in the mind and computational procedures that operate on those structures."

Bounded rationality is the idea that rationality is limited when individuals make decisions, and under these limitations, rational individuals will select a decision that is satisfactory rather than optimal.

Knowledge management (KM) is the collection of methods relating to creating, sharing, using and managing the knowledge and information of an organization. It refers to a multidisciplinary approach to achieve organizational objectives by making the best use of knowledge.

Organizational learning is the process of creating, retaining, and transferring knowledge within an organization. An organization improves over time as it gains experience. From this experience, it is able to create knowledge. This knowledge is broad, covering any topic that could better an organization. Examples may include ways to increase production efficiency or to develop beneficial investor relations. Knowledge is created at four different units: individual, group, organizational, and inter organizational.

In psychology, decision-making is regarded as the cognitive process resulting in the selection of a belief or a course of action among several possible alternative options. It could be either rational or irrational. The decision-making process is a reasoning process based on assumptions of values, preferences and beliefs of the decision-maker. Every decision-making process produces a final choice, which may or may not prompt action.

In psychology, cognitivism is a theoretical framework for understanding the mind that gained credence in the 1950s. The movement was a response to behaviorism, which cognitivists said neglected to explain cognition. Cognitive psychology derived its name from the Latin cognoscere, referring to knowing and information, thus cognitive psychology is an information-processing psychology derived in part from earlier traditions of the investigation of thought and problem solving.

Information processing is the change (processing) of information in any manner detectable by an observer. As such, it is a process that describes everything that happens (changes) in the universe, from the falling of a rock to the printing of a text file from a digital computer system. In the latter case, an information processor is changing the form of presentation of that text file. The computers up to this period function on the basis of programs saved in the memory, having no intelligence of their own.

A cognitive model is an approximation of one or more cognitive processes in humans or other animals for the purposes of comprehension and prediction. There are many types of cognitive models, and they can range from box-and-arrow diagrams to a set of equations to software programs that interact with the same tools that humans use to complete tasks. In terms of information processing, cognitive modeling is modeling of human perception, reasoning, memory and action.

Agency is the capacity of an actor to act in a given environment. It is independent of the moral dimension, which is called moral agency.

Personal knowledge management (PKM) is a process of collecting information that a person uses to gather, classify, store, search, retrieve and share knowledge in their daily activities and the way in which these processes support work activities. It is a response to the idea that knowledge workers need to be responsible for their own growth and learning. It is a bottom-up approach to knowledge management (KM).

Distributed cognition is an approach to cognitive science research that was developed by cognitive anthropologist Edwin Hutchins during the 1990s.

Theories of technological change and innovation attempt to explain the factors that shape technological innovation as well as the impact of technology on society and culture. Some of the most contemporary theories of technological change reject two of the previous views: the linear model of technological innovation and other, the technological determinism. To challenge the linear model, some of today's theories of technological change and innovation point to the history of technology, where they find evidence that technological innovation often gives rise to new scientific fields, and emphasizes the important role that social networks and cultural values play in creating and shaping technological artifacts. To challenge the so-called "technological determinism", today's theories of technological change emphasize the scope of the need of technical choice, which they find to be greater than most laypeople can realize; as scientists in philosophy of science, and further science and technology often like to say about this "It could have been different." For this reason, theorists who take these positions often argue that a greater public involvement in technological decision-making is desired.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to thought (thinking):

Transactive memory is a psychological hypothesis first proposed by Daniel Wegner in 1985 as a response to earlier theories of "group mind" such as groupthink. A transactive memory system is a mechanism through which groups collectively encode, store, and retrieve knowledge. Transactive memory was initially studied in couples and families where individuals had close relationships but was later extended to teams, larger groups, and organizations to explain how they develop a "group mind", a memory system that is more complex and potentially more effective than that of any of its individual constituents. A transactive memory system includes memory stored in each individual, the interactions between memory within the individuals, as well as the processes that update this memory. Transactive memory, then, is the shared store of knowledge.

Domain-general learning theories of development suggest that humans are born with mechanisms in the brain that exist to support and guide learning on a broad level, regardless of the type of information being learned. Domain-general learning theories also recognize that although learning different types of new information may be processed in the same way and in the same areas of the brain, different domains also function interdependently. Because these generalized domains work together, skills developed from one learned activity may translate into benefits with skills not yet learned. Another facet of domain-general learning theories is that knowledge within domains is cumulative, and builds under these domains over time to contribute to our greater knowledge structure. Psychologists whose theories align with domain-general framework include developmental psychologist Jean Piaget, who theorized that people develop a global knowledge structure which contains cohesive, whole knowledge internalized from experience, and psychologist Charles Spearman, whose work led to a theory on the existence of a single factor accounting for all general cognitive ability.

A knowledge organization is a management idea, describing an organization in which people use systems and processes to generate, transform, manage, use, and transfer knowledge-based products and services to achieve organizational goals.

David Krackhardt is Professor of Organizations at Heinz College and the Tepper School of Business, with courtesy appointments in the Department of Social and Decision Sciences and the Machine Learning Department, all at Carnegie Mellon University in the United States, and he also serves a Fellow of CEDEP, the European Centre for Executive Education, in France. He is notable for being the author of KrackPlot, a network visualization software designed for social network analysis which is widely used in academic research. He is also the founder of the Journal of Social Structure.

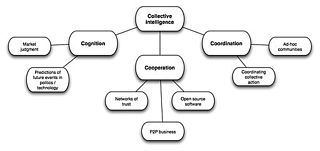

Collective intelligence (CI) is shared or group intelligence (GI) that emerges from the collaboration, collective efforts, and competition of many individuals and appears in consensus decision making. The term appears in sociobiology, political science and in context of mass peer review and crowdsourcing applications. It may involve consensus, social capital and formalisms such as voting systems, social media and other means of quantifying mass activity. Collective IQ is a measure of collective intelligence, although it is often used interchangeably with the term collective intelligence. Collective intelligence has also been attributed to bacteria and animals.

Cross-cultural psychology attempts to understand how individuals of different cultures interact with each other. Along these lines, cross-cultural leadership has developed as a way to understand leaders who work in the newly globalized market. Today's international organizations require leaders who can adjust to different environments quickly and work with partners and employees of other cultures. It cannot be assumed that a manager who is successful in one country will be successful in another.

The social sciences are the sciences concerned with societies, human behaviour, and social relationships.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cataldo, Jorge; Prochno, Paulo (2003) Cognitive assets: a model to understand the organizational appropriation of collective tacit knowledge. In Management of Technology Key Success Factors for Innovation and Sustainable Development. Editors: Morel-Guimaraes L Khalil T Hosni Y, 2005 pp: 123-133. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265406151

- ↑ Cataldo, Jorge (2001) Papel do Suporte Analítico à Tomada de Decisão na Gestão do Conhecimento Organizacional. Advised by Gomes, L. F. A. Ibmec Business School library.

- 1 2 Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H. (1995) The Knowledge Creating Company, Oxford University Press, New York.

- ↑ Eden, C. and Spender, J. C. (1998) Managerial and organizational cognition, Sage, London.

- 1 2 Fiol, C. M. (2002). Intraorganizational Cognition. In: Companion to Organizations (Ed, Baum, J. A.) Blackwell, Oxford.

- ↑ Birkinshaw, J., Nobel, R. and Ridderstrale, J. (2002). Knowledge as a contingency variable: Do the characteristics of knowledge predict organization structure? Organization Science, 13, 274-289.

- ↑ Orlikowski, W. (2002). Knowing in Practice: Enacting a Collective Capability in Distributed Organizing. Organization Science, 13, 249-273.

- ↑ Fiske, S. T. and Taylor, S. E. (1991) Social Cognition, McGraw Hill, New York.

- 1 2 Walsh, J. P. (1995). Managerial and organizational cognition: Notes from a trip down memory lane. Organization Science, 6, 280-321.

- ↑ Bartunek, J., Gordon, R. and Weathersby, R. (1983). Developing 'complicated' understanding in administrators. Academy of Management Review, 8, 273-284.

- ↑ Berne, E. (1973) Analisis transaccional en psicoterapia, Psique, Buenos Aires.

- ↑ Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, S95 - S120.

- ↑ Burt, R. S. (1992) Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition, Harvard University Press, Boston.

- ↑ Granovetter, M. (1973). The Strength of Weak Ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78, 1360-1380.

- ↑ Raider, H. and Krackhardt, D. (2002). Intraorganizational Networks. In: Companion to Organizations (Ed, Baum, J. A.) Blackwell, Oxford.

- ↑ Dyer, J. H. and Nobeoka, K. (2000). Creating and maintaining a high performance knowledge-sharing network: The Toyota Case. Strategic Management Journal, 21, 345-367.