In jurisprudence, double jeopardy is a procedural defence that prevents an accused person from being tried again on the same charges following an acquittal or conviction and in rare cases prosecutorial and/or judge misconduct in the same jurisdiction. Double jeopardy is a common concept in criminal law. In civil law, a similar concept is that of res judicata. Variation in common law countries is the peremptory plea, which may take the specific forms of autrefois acquit or autrefois convict. These doctrines appear to have originated in ancient Roman law, in the broader principle non bis in idem.

Laws prohibiting blasphemy and blasphemous libel in the United Kingdom date back to the mediaeval times as common law and in some special cases as enacted legislation. The common law offences of blasphemy and blasphemous libel were formally abolished in England and Wales in 2008 and Scotland in 2021. Equivalent laws remain in Northern Ireland.

Marcus Morton was an American lawyer, jurist, and politician from Taunton, Massachusetts. He served two terms as Governor of Massachusetts and several months as Acting Governor following the death in 1825 of William Eustis. He served for 15 years as an associate justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, all the while running unsuccessfully as a Democrat for governor. He finally won the 1839 election, acquiring exactly the number of votes required for a majority win over Edward Everett. After losing the 1840 and 1841 elections, he was elected in a narrow victory in 1842.

Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616 (1919), was a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States upholding the 1918 Amendment to the Espionage Act of 1917 which made it a criminal offense to urge the curtailment of production of the materials necessary to wage the war against Germany with intent to hinder the progress of the war. The 1918 Amendment is commonly referred to as if it were a separate Act, the Sedition Act of 1918.

Leonard Williams Levy was an American historian, the Andrew W. Mellon All-Claremont Professor of Humanities and chairman of the Graduate Faculty of History at Claremont Graduate School, California, who specialized in the history of basic American Constitutional freedoms.

Thomas Aikenhead was a Scottish student from Edinburgh, who was prosecuted and executed at the age of 20 on a charge of blasphemy under the Act against Blasphemy 1661 and Act against Blasphemy 1695. He was the last person in Great Britain to be executed for blasphemy. His execution occurred 85 years after the death of Edward Wightman (1612), the last person to be burned at the stake for heresy in England.

Abner Kneeland was an American evangelist and theologian who advocated views on women's rights, racial equality, and religious skepticism that were radical for his day. As a young man, Kneeland was a lay preacher in a Baptist church, but he converted to Universalism and was ordained as a minister. Later in life, he rejected revealed religion and Universalism's Christian God. Due to provocative statements he published, Massachusetts convicted Kneeland under its rarely used blasphemy law. Kneeland was the last man in the United States jailed for blasphemy. After his sentence, he founded a utopian society in Iowa, but it failed shortly after his death.

The legal system of South Korea is a civil law system that has its basis in the Constitution of the Republic of Korea. The Court Organization Act, which was passed into law on 26 September 1949, officially created a three-tiered, independent judicial system. The revised Constitution of 1987 codified judicial independence in Article 103, which states that, "Judges rule independently according to their conscience and in conformity with the Constitution and the law." The 1987 rewrite also established the Constitutional Court, the first time that South Korea had an active body for constitutional review.

The Double Jeopardy Clause of the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution provides: "[N]or shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb..." The four essential protections included are prohibitions against, for the same offense:

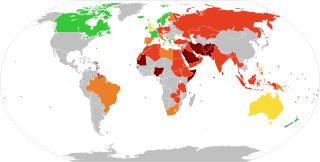

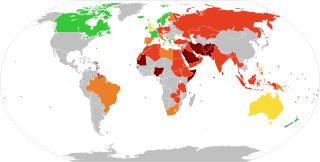

A blasphemy law is a law prohibiting blasphemy, which is the act of insulting or showing contempt or lack of reverence to a deity, or sacred objects, or toward something considered sacred or inviolable. According to Pew Research Center, about a quarter of the world's countries and territories (26%) had anti-blasphemy laws or policies as of 2014.

In the 20th century, the United States began to invalidate laws against blasphemy which had been on the books since before the founding of the nation, or prosecutions on that ground, as it was decided that they violated the American Constitution. The First Amendment to the United States Constitution provides that "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press...", and these restrictions were extended to state and local governments in the early 20th century. While there are no federal laws which forbid "religious vilification" or "religious insult" or "hate speech", some states have blasphemy statutes.

North v. Russell, 427 U.S. 328 (1976), is a United States Supreme Court case which held that a non-lawyer jurist can constitutionally sit in a jail-carrying criminal case provided that the defendant has an opportunity through an appeal to obtain a second trial before a judge who is a lawyer.

United States v. Dinitz, 424 U.S. 600 (1976), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States determined that the U.S. Const., Amend. V protection against double jeopardy did not prevent a retrial of a defendant, who had previously requested a mistrial.

Ludwig v. Massachusetts, 427 U.S. 618 (1976), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that the Massachusetts two-tier court system did not deprive Ludwig of his U.S. Const., Amend. XIV right to a jury trial and did not violate the double jeopardy clause of the U.S. Const., Amend. V.

North Carolina v. Pearce, 395 U.S. 711 (1969), is a United States Supreme Court case that forbids judicial “vindictiveness” from playing a role in the increased sentence a defendant receives after a new trial. In sum, due process requires that a defendant be “free of apprehension” of judicial vindictiveness. Time served for a new conviction of the same offense must be “fully credited,” and a trial judge seeking to impose a greater sentence on retrial must affirmatively state the reasons for imposing such a sentence.

Richmond Newspapers Inc. v. Virginia, 448 U.S. 555 (1980), is a United States Supreme Court case involving issues of privacy in correspondence with the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, the freedom of the press, the Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution and the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. After a murder case ended in three mistrials, the judge closed the fourth trial to the public and the press. On appeal, the Supreme Court ruled the closing to be in violation of the First Amendment and Fourteenth Amendment asserting that the First Amendment implicitly guarantees the press access to public trials.

Lafler v. Cooper, 566 U.S. 156 (2012), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court clarified the Sixth Amendment standard for reversing convictions due to ineffective assistance of counsel during plea bargaining. The Court ruled that when a lawyer's ineffective assistance leads to the rejection of a plea agreement, a defendant is entitled to relief if the outcome of the plea process would have been different with competent advice. In such cases, the Court ruled that the Sixth Amendment requires the trial judge to exercise discretion to determine an appropriate remedy.

Oregon v. Kennedy, 456 U.S. 667 (1982), was a United States Supreme Court decision dealing with the appropriate test for determining whether a criminal defendant has been "goaded" by the prosecution's bad actions into motioning for a mistrial. This matters because the answer determines whether a defendant can be retried. Ordinarily, a defendant who requests a mistrial can be forced to stand trial a second time, see United States v. Dinitz. However, if the prosecution's conduct was "intended to provoke the defendant into moving for a mistrial," double jeopardy protects the defendant from retrial. The Court emphasized that only prosecutorial actions where the intent is to provoke a mistrial — and not mere "harassment" or "overreaching" — trigger the double jeopardy protection.

Samuel Dunn Parker (1781–1873) was an American attorney who served as District Attorney of Suffolk County, Massachusetts.

Ramos v. Louisiana, 590 U.S. ___ (2020), was a U.S. Supreme Court decision in which the Court ruled that the Sixth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution requires that guilty verdicts be unanimous in trials for serious crimes. Only cases in Oregon and Louisiana were affected by the ruling because every other state already had this requirement. The decision incorporated the Sixth Amendment requirement for unanimous jury criminal convictions against the states, and thereby overturned the Court's previous decision from the 1972 cases Apodaca v. Oregon and Johnson v. Louisiana.