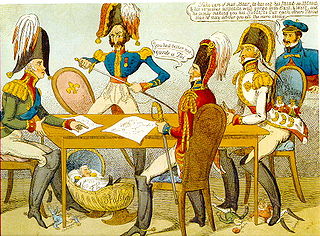

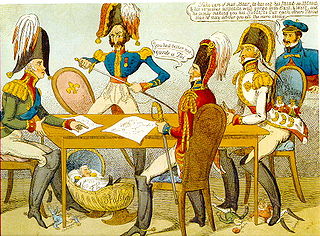

The Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte. Participants were representatives of all European powers and other stakeholders. The Congress was chaired by Austrian statesman Klemens von Metternich, and was held in Vienna from September 1814 to June 1815.

Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar, Prince of Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein, known as Klemens von Metternich or Prince Metternich, was a conservative Austrian statesman and diplomat who was at the center of the European balance of power known as the Concert of Europe for three decades as the Austrian Empire's foreign minister from 1809 and Chancellor from 1821 until the liberal Revolutions of 1848 forced his resignation.

Robert Stewart, 2nd Marquess of Londonderry,, usually known as Lord Castlereagh, derived from the courtesy title Viscount Castlereagh by which he was styled from 1796 to 1821, was a British statesman and politician. As secretary to the Viceroy in Ireland, he worked to suppress the Rebellion of 1798 and to secure passage in 1800 of the Irish Act of Union. As the Foreign Secretary of the United Kingdom from 1812, he was central to the management of the coalition that defeated Napoleon, and was British plenipotentiary at the Congress of Vienna. In the post-war government of Lord Liverpool, Castlereagh was seen to support harsh measures against agitation for reform, and he ended his life an isolated and unpopular figure.

Ferdinand I was King of the Two Sicilies from 1816 until his death. Before that he had been, since 1759, King of Naples as Ferdinand IV and King of Sicily as Ferdinand III. He was deposed twice from the throne of Naples: once by the revolutionary Parthenopean Republic for six months in 1799, and again by a French invasion in 1806, before being restored in 1815 at the end of the Napoleonic Wars.

Karl August Fürst von Hardenberg was a Prussian statesman and Chief Minister of Prussia. While during his late career he acquiesced to reactionary policies, earlier in his career he implemented a variety of Liberal reforms. To him and Baron vom Stein, Prussia was indebted for improvements in its army system, the abolition of serfdom and feudal burdens, the throwing open of the civil service to all classes, and the complete reform of the educational system.

The Congress of Troppau was a conference of the Quintuple Alliance to discuss means of suppressing the revolution in Naples of July 1820, and at which the Troppau Protocol was signed on 19 November 1820.

The Concert of Europe was a general agreement among the great powers of 19th-century Europe to maintain the European balance of power, political boundaries, and spheres of influence. Never a perfect unity and subject to disputes and jockeying for position and influence, the Concert was an extended period of relative peace and stability in Europe following the Wars of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars which had consumed the continent since the 1790s. There is considerable scholarly dispute over the exact nature and duration of the Concert. Some scholars argue that it fell apart nearly as soon as it began in the 1820s when the great powers disagreed over the handling of liberal revolts in Italy, while others argue that it lasted until the outbreak of World War I and others for points in between. For those arguing for a longer duration, there is generally agreement that the period after the Revolutions of 1848 and the Crimean War (1853–1856) represented a different phase with different dynamics than the earlier period.

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a multinational European great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, it was the third most populous monarchy in Europe after the Russian Empire and the United Kingdom. Along with Prussia, it was one of the two major powers of the German Confederation. Geographically, it was the third-largest empire in Europe after the Russian Empire and the First French Empire.

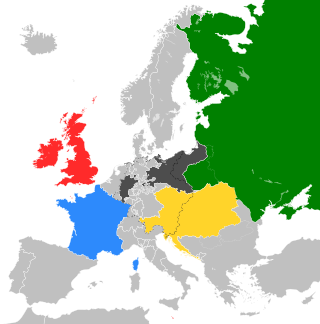

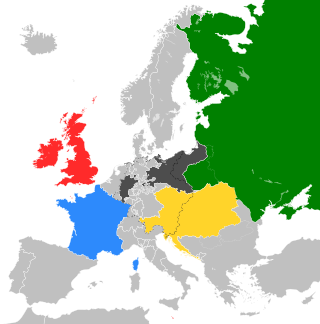

The Quintuple Alliance came into being at the Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1818, when France joined the Quadruple Alliance created by Austria, Prussia, the Russian Empire, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The European peace settlement concluded at the Congress of Vienna in 1815.

The Holy Alliance, also called the Grand Alliance, was a coalition linking the monarchist great powers of Austria, Prussia, and Russia, which was created after the final defeat of Napoleon at the behest of Emperor (Tsar) Alexander I of Russia and signed in Paris on 26 September 1815.

The Conservative Order was the period in political history of Europe after the defeat of Napoleon in 1815. From 1815 to 1830, a conscious program by conservative statesmen, including Metternich and Castlereagh, was put into place to contain revolution and revolutionary forces by restoring the old orders, particularly the previously-ruling aristocracies. On the other hand, in South America, in light of the Monroe Doctrine, the Spanish and the Portuguese colonies gained independence.

The Congress of Verona met at Verona from 20 October to 14 December 1822 as part of the series of international conferences or congresses that opened with the Congress of Vienna in 1814–15, which had instituted the Concert of Europe at the close of the Napoleonic Wars.

The Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle, held in the autumn of 1818, was a high-level diplomatic meeting of France and the four allied powers Britain, Austria, Prussia and Russia, which had defeated it in 1814. The purpose was to decide the withdrawal of the army of occupation from France and renegotiate the reparations it owed. It produced an amicable settlement, whereby France refinanced its reparations debt; the Allies in a few weeks withdrew all of their troops.

The Paris Declaration respecting Maritime Law of 16 April 1856 was an international multilateral treaty agreed to by the warring parties in the Crimean War gathered at the Congress at Paris after the peace treaty of Paris had been signed in March 1856. As an important juridical novelty in international law the treaty for the first time created the possibility for nations that were not involved in the establishment of the agreement and did not sign, to become a party by acceding the declaration afterwards. So did altogether 55 nations, which otherwise would have been impossible in such a short period. This represented a large step in the globalisation of international law.

Friedrich von Gentz was an Austrian diplomat and a writer. With Austrian chancellor Klemens von Metternich he was one of the main forces behind the organisation, management and protocol of the Congress of Vienna.

The Treaties of Reichenbach were a series of agreements signed in Reichenbach between Great Britain, Prussia, Russia, and Austria. These accords served to establish and strengthen a united coalition force against Napoleon I of France.

Alexander I, nicknamed "the Blessed", was Emperor of Russia from 1801, the first king of Congress Poland from 1815, and the grand duke of Finland from 1809 to his death in 1825. He was the eldest son of Emperor Paul I and Sophie Dorothea of Württemberg.

The Protocol of St. Petersburg was an 1826 Anglo-Russian agreement for the settlement of the Greek War of Independence.

The Secret Treaty of Vienna was a defensive alliance signed on 3 January 1815 by France, the Austrian Empire and Great Britain. It took place during the Congress of Vienna, negotiations on the future of Europe following Napoleon's defeat in the War of the Sixth Coalition.

The Congress of Châtillon was a peace conference held at Châtillon-sur-Seine, north-eastern France, from 5 February to 5 March 1814, in the latter stages of the War of the Sixth Coalition. Peace had previously been offered by the Coalition allies to Napoleon I's France in the November 1813 Frankfurt proposals. These proposals required that France revert to her "natural borders" of the Rhine, Pyrenees and the Alps. Napoleon was reluctant to lose his territories in Germany and Italy and refused the proposals. By December the French had been pushed back in Germany and Napoleon indicated that he would accept peace on the Frankfurt terms. The Coalition however now sought to reduce France to her 1791 borders, which would not include Belgium.