The Irish Civil War was a conflict that followed the Irish War of Independence and accompanied the establishment of the Irish Free State, an entity independent from the United Kingdom but within the British Empire.

The Oireachtas, sometimes referred to as Oireachtas Éireann, is the bicameral parliament of Ireland. The Oireachtas consists of the president of Ireland and the two houses of the Oireachtas, a house of representatives called Dáil Éireann and a senate called Seanad Éireann.

The First Dáil was Dáil Éireann as it convened from 1919 to 1921. It was the first meeting of the unicameral parliament of the revolutionary Irish Republic. In the December 1918 election to the Parliament of the United Kingdom, the Irish republican party Sinn Féin won a landslide victory in Ireland. In line with their manifesto, its MPs refused to take their seats, and on 21 January 1919 they founded a separate parliament in Dublin called Dáil Éireann. They declared Irish independence, ratifying the Proclamation of the Irish Republic that had been issued in the 1916 Easter Rising, and adopted a provisional constitution.

Cathal Brugha was an Irish republican politician who served as Minister for Defence from 1919 to 1922, Ceann Comhairle of Dáil Éireann in January 1919, the first president of Dáil Éireann from January 1919 to April 1919 and Chief of Staff of the Irish Republican Army from 1917 to 1918. He served as a Teachta Dála (TD) from 1918 to 1922.

The Defence Forces are the armed forces of Ireland. They encompass the Army, Air Corps, Naval Service, and Reserve Defence Forces.

Dáil Éireann, also called the Revolutionary Dáil, was the revolutionary, unicameral parliament of the Irish Republic from 1919 to 1922. The Dáil was first formed on 21 January 1919 in Dublin by 69 Sinn Féin MPs elected in the 1918 United Kingdom general election, who had won 73 seats of the 105 seats in Ireland, with four party candidates elected for two constituencies. Their manifesto refused to recognise the British parliament at Westminster and instead established an independent legislature in Dublin. The convention of the First Dáil coincided with the beginning of the War of Independence.

Events from the year 1922 in Ireland.

The Minister for the Co-ordination of Defensive Measures was the title of Frank Aiken as a member of the Government of Ireland from 8 September 1939 to 18 June 1945 during The Emergency — the state of emergency in operation in Ireland during World War II. The Minister was intended to handle Civil Defence and related measures, allowing the Minister for Defence to concentrate on matters relating to the regular Army. The office was also responsible for handling wartime censorship.

Patrick John Little was an Irish Fianna Fáil politician. A founder-member of the party, he served in a number of cabinet positions, most notably as the country's longest-serving Minister for Posts and Telegraphs.

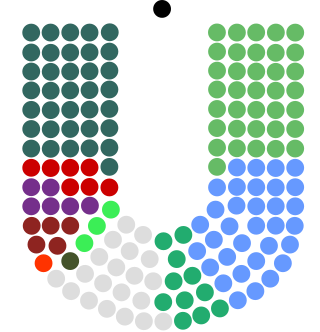

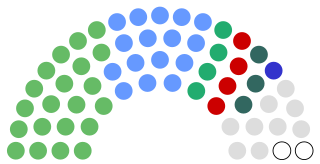

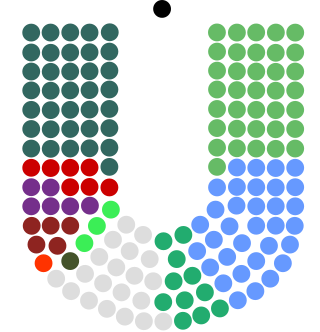

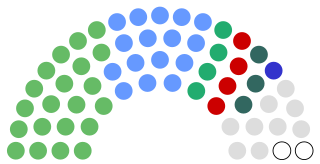

The members of the First Dáil, known as Teachtaí Dála (TDs), were the 101 Members of Parliament (MPs) returned from constituencies in Ireland at the 1918 United Kingdom general election. In its first general election, Sinn Féin won 73 seats and viewed the result as a mandate for independence; in accordance with its declared policy of abstentionism, its 69 MPs refused to attend the British House of Commons in Westminster, and established a revolutionary parliament known as Dáil Éireann. The other Irish MPs — 26 unionists and six from the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) — sat at Westminster and for the most part ignored the invitation to attend the Dáil. Thomas Harbison, IPP MP for North East Tyrone, did acknowledge the invitation, but "stated he should decline for obvious reasons". The Dáil met for the first time on 21 January 1919 in Mansion House in Dublin. Only 27 members attended; most of the other Sinn Féin TDs were imprisoned by the British authorities, or in hiding under threat of arrest. All 101 MPs were considered TDs, and their names were called out on the roll of membership, though there was some laughter when Irish Unionist Alliance leader Edward Carson was described as as láthair ("absent"). The database of members of the Oireachtas includes for the First Dáil only those elected for Sinn Féin.

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various resistance organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dedicated to anti-imperialism through Irish republicanism, the belief that all of Ireland should be an independent republic free from British colonial rule.

Irish republican legitimism denies the legitimacy of the political entities of the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland and posits that the pre-partition Irish Republic continues to exist. It is a more extreme form of Irish republicanism, which denotes rejection of all British rule in Ireland. The concept shapes aspects of, but is not synonymous with, abstentionism.

Comhairle na dTeachtaí was an Irish republican parliament established by opponents of the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty and the resulting Irish Free State, and viewed by republican legitimatists as a successor to the Second Dáil. Members were abstentionist from the Third Dáil established by the pro-Treaty faction. Just as the First Dáil established a parallel Irish Republic in opposition to the British Dublin Castle administration, so Comhairle na dTeachtaí attempted to establish a legitimatist government in opposition to the Provisional Government and Government of the Irish Free State established by the Third Dáil. This legitimatist government, called the Council of State, had Éamon de Valera as president. In 1926 de Valera resigned as president, left the Sinn Féin party and founded Fianna Fáil, which in 1927 entered the Fourth Dáil. Comhairle na dTeachtaí, never more than a symbolic body, was thereby rendered defunct.

In the United Kingdom, military conscription has existed for two periods in modern times. The first was from 1916 to 1920, and the second from 1939 to 1960. The last conscripted soldiers left the service in 1963.

The Emergency Powers Act 1939 (EPA) was an Act of the Oireachtas enacted on 3 September 1939, after an official state of emergency had been declared on 2 September 1939 in response to the outbreak of the Second World War. The Act empowered the government to:

make provisions for securing the public safety and the preservation of the state in time of war and, in particular, to make provision for the maintenance of public order and for the provision and control of supplies and services essential to the life of the community, and to provide for divers and other matters connected with the matters aforesaid.

Seanad Éireann is the upper house of the Oireachtas, which also comprises the President of Ireland and Dáil Éireann.

Pádraig Mac Lochlainn is an Irish Sinn Féin politician who has been a Teachta Dála (TD) for the Donegal constituency since the 2020 general election, and previously from 2011 to 2016 for the Donegal North-East constituency. He previously served as a Senator for the Industrial and Commercial Panel from 2016 to 2020.

Emergency Powers Order 1945 or EPO 362 was an Irish ministerial order which penalised members of the Irish Defence Forces who had deserted since the beginning of the Emergency proclaimed at the start of World War II, during which the state was neutral. The order deprived those affected of pension entitlements and unemployment benefits accrued prior to their desertion, and prohibited them from employment in the public sector for a period of seven years. Most of those affected had deserted to join the armed forces of belligerents: in almost all cases those of the Allies, and mainly the British Armed Forces.

The revolutionary period in Irish history was the period in the 1910s and early 1920s when Irish nationalist opinion shifted from the Home Rule-supporting Irish Parliamentary Party to the republican Sinn Féin movement. There were several waves of civil unrest linked to Ulster loyalism, trade unionism, and physical force republicanism, leading to the Irish War of Independence, the Partition of Ireland, the creation of the Irish Free State, and the Irish Civil War.