Related Research Articles

The European Convention on Human Rights is an international convention to protect human rights and political freedoms in Europe. Drafted in 1950 by the then newly formed Council of Europe, the convention entered into force on 3 September 1953. All Council of Europe member states are party to the convention and new members are expected to ratify the convention at the earliest opportunity.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child is an international human rights treaty which sets out the civil, political, economic, social, health and cultural rights of children. The convention defines a child as any human being under the age of eighteen, unless the age of majority is attained earlier under national legislation.

Bioethics is both a field of study and professional practice, interested in ethical issues related to health, including those emerging from advances in biology, medicine, and technologies. It proposes the discussion about moral discernment in society and it is often related to medical policy and practice, but also to broader questions as environment, well-being and public health. Bioethics is concerned with the ethical questions that arise in the relationships among life sciences, biotechnology, medicine, politics, law, theology and philosophy. It includes the study of values relating to primary care, other branches of medicine, ethical education in science, animal, and environmental ethics, and public health.

Dignity is the right of a person to be valued and respected for their own sake, and to be treated ethically. It is of significance in morality, ethics, law and politics as an extension of the Enlightenment-era concepts of inherent, inalienable rights. The term may also be used to describe personal conduct, as in "behaving with dignity".

The American Convention on Human Rights, also known as the Pact of San José, is an international human rights instrument. It was adopted by many countries in the Western Hemisphere in San José, Costa Rica, on 22 November 1969. It came into force after the eleventh instrument of ratification was deposited on 18 July 1978.

S1909/A2840 is a bill that was passed by the New Jersey Legislature in December 2003, and signed into law by Governor James McGreevey on January 4, 2004, that permits human cloning for the purpose of developing and harvesting human stem cells. Specifically, it legalizes the process of cloning a human embryo, and implanting the clone into a womb, provided that the clone is then aborted and used for medical research. The legislation was sponsored by Senators Richard Codey (D-Essex) and Barbara Buono, and Assembly members Neil M. Cohen (D-Union), John F. McKeon, Mims Hackett (D-Essex), and Joan M. Quigley (D-Hudson). The enactment of this law will enable researchers to find cures for debilitating and deadly diseases.

The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (CFR) enshrines certain political, social, and economic rights for European Union (EU) citizens and residents into EU law. It was drafted by the European Convention and solemnly proclaimed on 7 December 2000 by the European Parliament, the Council of Ministers and the European Commission. However, its then legal status was uncertain and it did not have full legal effect until the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon on 1 December 2009.

The African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights is an international human rights instrument that is intended to promote and protect human rights and basic freedoms in the African continent.

A designer baby is a baby whose genetic makeup has been selected or altered, often to exclude a particular gene or to remove genes associated with disease. This process usually involves analysing a wide range of human embryos to identify genes associated with particular diseases and characteristics, and selecting embryos that have the desired genetic makeup; a process known as preimplantation genetic diagnosis. Screening for single genes is commonly practiced, and polygenic screening is offered by a few companies. Other methods by which a baby's genetic information can be altered involve directly editing the genome before birth, which is not routinely performed and only one instance of this is known to have occurred as of 2019, where Chinese twins Lulu and Nana were edited as embryos, causing widespread criticism.

Economic, social and cultural rights (ESCR) are socio-economic human rights, such as the right to education, right to housing, right to an adequate standard of living, right to health, victims' rights and the right to science and culture. Economic, social and cultural rights are recognised and protected in international and regional human rights instruments. Member states have a legal obligation to respect, protect and fulfil economic, social and cultural rights and are expected to take "progressive action" towards their fulfilment.

Human rights are largely respected in Switzerland, one of Europe's oldest democracies. Switzerland is often at or near the top in international rankings of civil liberties and political rights observance. Switzerland places human rights at the core of the nation's value system, as represented in its Federal Constitution. As described in its FDFA's Foreign Policy Strategy 2016-2019, the promotion of peace, mutual respect, equality and non-discrimination are central to the country's foreign relations.

Chapter Two of the Constitution of South Africa contains the Bill of Rights, a human rights charter that protects the civil, political and socio-economic rights of all people in South Africa. The rights in the Bill apply to all law, including the common law, and bind all branches of the government, including the national executive, Parliament, the judiciary, provincial governments, and municipal councils. Some provisions, such as those prohibiting unfair discrimination, also apply to the actions of private persons.

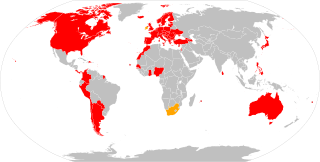

The Convention on Cybercrime, also known as the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime or the Budapest Convention, is the first international treaty seeking to address Internet and computer crime (cybercrime) by harmonizing national laws, improving investigative techniques, and increasing cooperation among nations. It was drawn up by the Council of Europe in Strasbourg, France, with the active participation of the Council of Europe's observer states Canada, Japan, the Philippines, South Africa and the United States.

Stem cell research policy varies significantly throughout the world. There are overlapping jurisdictions of international organizations, nations, and states or provinces. Some government policies determine what is allowed versus prohibited, whereas others outline what research can be publicly financed. Of course, all practices not prohibited are implicitly permitted. Some organizations have issued recommended guidelines for how stem cell research is to be conducted.

Roberto Andorno is Privatdozent at the Faculty of Law, University of Zurich (Switzerland). He is also Research Fellow at the University's Institute of Biomedical Ethics and Medical History, where he also coordinates the PhD Program in biomedical ethics and law. Originally from Argentina, he holds doctoral degrees in law from the Universities of Buenos Aires (1991) and Paris XII (1994), both on topics related to the ethical and legal aspects of assisted reproductive technologies. Between 1999 and 2005 he conducted various research projects relating to global bioethics, human dignity, and human rights at the Laval University, and at the Universities of Göttingen and Tübingen, in Germany.

The International Bioethics Committee (IBC) of UNESCO is a body composed of 36 independent experts from all regions and different disciplines that follows progress in the life sciences and its applications in order to ensure respect for human dignity and human rights. It was created in 1993 by Dr Federico Mayor Zaragoza, General Director of UNESCO at that time. It has been prominent in developing Declarations with regard to norms of bioethics that are regarded as soft law but are nonetheless influential in shaping the deliberations, for example, of research ethics committees and health policy.

The Nuffield Council on Bioethics is a UK-based independent charitable body, which examines and reports on bioethical issues raised by new advances in biological and medical research. Established in 1991, the Council is funded by the Nuffield Foundation, the Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust. The Council has been described by the media as a 'leading ethics watchdog', which 'never shrinks from the unthinkable'.

A biological patent is a patent on an invention in the field of biology that by law allows the patent holder to exclude others from making, using, selling, or importing the protected invention for a limited period of time. The scope and reach of biological patents vary among jurisdictions, and may include biological technology and products, genetically modified organisms and genetic material. The applicability of patents to substances and processes wholly or partially natural in origin is a subject of debate.

Claudia Wiesemann is a German medical ethicist and medical historian. She is full professor and head of the Department of Medical Ethics and History of Medicine at Göttingen University Medical Center. Being a member of the German Ethics Council since 2012, she was elected Deputy Chair in 2016.

Judit Sándor is a Hungarian lawyer, bioethicist, and author, as well as full professor at the Department of Political Science, Department of Legal Studies and the Department of Gender Studies of the Central European University (CEU), Budapest. She had a bar exam in Hungary before she conducted legal practice at Simmons & Simmons in London. In 1996 she received Ph.D. in law and political science at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

References

- ↑ Roberto Andorno, The Oviedo Convention: A European Legal Framework at the Intersection of Human Rights and Health Law, JIBL Vol 02, 2005

- ↑ Ismini Kriari-Cataris, The Convention for the protection of human rights and dignity of the human being with regard to the application of biology and medicine: Convention on human rights and biomedicine, Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences Athens, Greece, Journal of Asian and International Bioethics, 12 (2002) 90-93

- ↑ Roberto Andorno, The Oviedo Convention: A European Legal Framework at the Intersection of Human Rights and Health Law, JIBL Vol 02, 2005

- ↑ Henriette Roscam Abbing, The Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine. An Appraisal of the Council of Europe Convention, European Journal of Health Law, 1998, no.5, p.379

- ↑ Explanatory Report

- ↑ Explanatory Report

- ↑ Committee on Bioethics

- ↑ Committee of Ministers

- ↑ Roberto Andorno, The Oviedo Convention: A European Legal Framework at the Intersection of Human Rights and Health Law, JIBL Vol 02, 2005

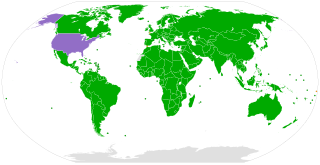

- ↑ "Parties to the Oviedo Convention". Treaty Office. Retrieved 2018-08-08.

- ↑ Parties to the Oviedo Convention

- ↑ Roberto Andorno, The Oviedo Convention: A European Legal Framework at the Intersection of Human Rights and Health Law, JIBL Vol 02, 2005

- ↑ UDHR

- ↑ ICCPR

- ↑ ICESCR

- ↑ CRC

- ↑ ECHR Archived July 1, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ European Social Charter

- ↑ The Oviedo Convention, Article 5

- ↑ The Oviedo Convention, Chapter II

- ↑ The Oviedo Convention, Chapter III

- ↑ The Oviedo Convention, Article 11

- ↑ The Oviedo Convention, Article 12

- ↑ Explanatory Report

- ↑ The Oviedo Convention, Article 13

- ↑ World Congress for Freedom of Research

- ↑ The Oviedo Convention, Chapter V

- ↑ The Oviedo Convention, Article 15

- ↑ The Oviedo Convention, Article 16

- ↑ The Oviedo Convention, Chapter II

- ↑ The Oviedo Convention, Article 18

- ↑ The Oviedo Convention, Chapter VI

- ↑ Explanatory Report, para 132

- ↑ The Oviedo Convention, Article 24

- ↑ The Oviedo Convention, Article 25

- ↑ Explanatory Report, para 161-162

- ↑ Explanatory Report, para 164

- ↑ Protocol on the Prohibition of Cloning Human Beings

- ↑ Protocol on Transplantation

- ↑ Protocol on Biomedical Research

- ↑ Protocol on Genetic Testing for Health Purposes