The Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime. The amendment was passed by the Senate on April 8, 1864, by the House of Representatives on January 31, 1865, and ratified by the required 27 of the then 36 states on December 6, 1865, and proclaimed on December 18. It was the first of the three Reconstruction Amendments adopted following the American Civil War.

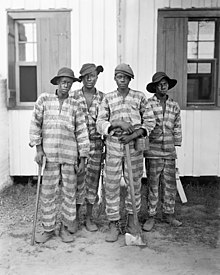

A chain gang or road gang is a group of prisoners chained together to perform menial or physically challenging work as a form of punishment. Such punishment might include repairing buildings, building roads, or clearing land. The system was notably used in the convict era of Australia and in the Southern United States. By 1955 it had largely been phased out in the U.S., with Georgia among the last states to abandon the practice. North Carolina continued to use chain gangs into the 1970s. Chain gangs were reintroduced by a few states during the "get tough on crime" 1990s: In 1995, Alabama was the first state to revive them. The experiment ended after about one year in all states except Arizona, where in Maricopa County inmates can still volunteer for a chain gang to earn credit toward a high school diploma or avoid disciplinary lockdowns for rule infractions.

Peon usually refers to a person subject to peonage: any form of wage labor, financial exploitation, coercive economic practice, or policy in which the victim or a laborer (peon) has little control over employment or economic conditions. Peon and peonage can refer to both the colonial period and post-colonial period of Latin America, as well as the period after the end of slavery in the United States, when "Black Codes" were passed to retain African-American freedmen as labor through other means.

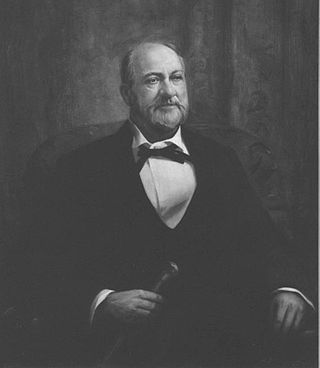

Joseph Emerson Brown, often referred to as Joe Brown, was an American attorney and politician, serving as the 42nd Governor of Georgia from 1857 to 1865, the only governor to serve four terms. He also served as a United States Senator from that state from 1880 to 1891.

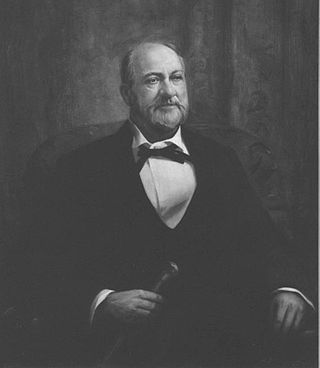

Braxton Bragg Comer was an American politician who served as the 33rd governor of Alabama from 1907 to 1911, and a United States senator in 1920. As governor, he achieved railroad reform, lowering business rates in Alabama to make them more competitive with other states. He increased funding for the public school system, resulting in more rural schools and high schools in each county for white students and a rise in the state's literacy rate.

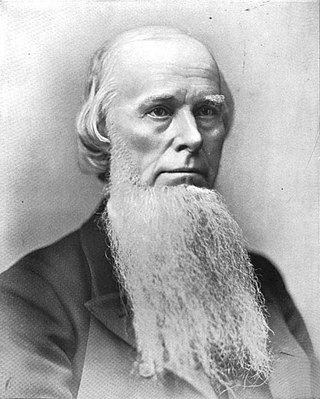

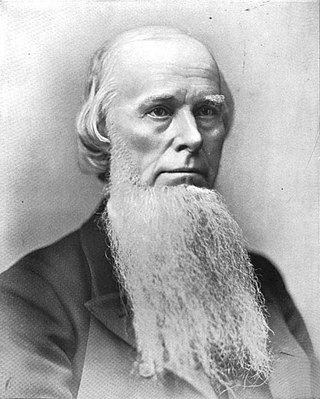

Peter Turney was an American politician, soldier, and jurist, who served as the 26th governor of Tennessee from 1893 to 1897. He was also a justice of the Tennessee Supreme Court from 1870 to 1893, and served as the court's Chief Justice from 1886 to 1893. During the Civil War, Turney was colonel of the First Tennessee Regiment, one of the first Tennessee units to join the Confederate Army.

The Black Codes, sometimes called the Black Laws, were laws which governed the conduct of African Americans. In 1832, James Kent wrote that "in most of the United States, there is a distinction in respect to political privileges, between free white persons and free colored persons of African blood; and in no part of the country do the latter, in point of fact, participate equally with the whites, in the exercise of civil and political rights." Although Black Codes existed before the Civil War and although many Northern states had them, the Southern U.S. states codified such laws in everyday practice. The best known of these laws were passed by Southern states in 1865 and 1866, after the Civil War, in order to restrict African Americans' freedom, and in order to compel them to work for either low or no wages.

Joel Hurt (1850–1926) was an American businessman. He was the president of Trust Company of Georgia, and a developer in Atlanta. He was one of the many founders of SunTrust Bank.

Tennessee State Prison is a former correctional facility located six miles west of downtown Nashville, Tennessee on Cockrill Bend. It opened in 1898 and has been closed since 1992 because of overcrowding concerns. The mothballed facility was severely damaged by an EF3 tornado in the tornado outbreak of March 2–3, 2020.

The "trusty system" was a penitentiary system of discipline and security enforced in parts of the United States until the 1980s, in which designated inmates were given various privileges, abilities, and responsibilities not available to all inmates.

Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II is a book by American writer Douglas A. Blackmon, published by Anchor Books in 2008. It explores the forced labor of prisoners, overwhelmingly African American men, through the convict lease system used by states, local governments, white farmers, and corporations after the American Civil War until World War II in the southern United States. Blackmon argues that slavery in the United States did not end with the Civil War, but instead persisted well into the 20th century. It depicts the subjugation of convict leasing, sharecropping and peonage and tells the fate of the former but not of the latter two.

The Coal Creek War was an early 1890s armed labor uprising in the southeastern United States that took place primarily in Anderson County, Tennessee. This labor conflict ignited during 1891 when coal mine owners in the Coal Creek watershed began to remove and replace their company-employed, private coal miners then on the payroll with convict laborers leased out by the Tennessee state prison system.

Imprisonment began to replace other forms of criminal punishment in the United States just before the American Revolution, though penal incarceration efforts had been ongoing in England since as early as the 1500s, and prisons in the form of dungeons and various detention facilities had existed as early as the first sovereign states. In colonial times, courts and magistrates would impose punishments including fines, forced labor, public restraint, flogging, maiming, and death, with sheriffs detaining some defendants awaiting trial. The use of confinement as a punishment in itself was originally seen as a more humane alternative to capital and corporal punishment, especially among Quakers in Pennsylvania. Prison building efforts in the United States came in three major waves. The first began during the Jacksonian Era and led to the widespread use of imprisonment and rehabilitative labor as the primary penalty for most crimes in nearly all states by the time of the American Civil War. The second began after the Civil War and gained momentum during the Progressive Era, bringing a number of new mechanisms—such as parole, probation, and indeterminate sentencing—into the mainstream of American penal practice. Finally, since the early 1970s, the United States has engaged in a historically unprecedented expansion of its imprisonment systems at both the federal and state level. Since 1973, the number of incarcerated persons in the United States has increased five-fold. Now, about 2,200,000 people, or 3.2 percent of the adult population, are imprisoned in the United States, and about 7,000,000 are under supervision of some form in the correctional system, including parole and probation. Periods of prison construction and reform produced major changes in the structure of prison systems and their missions, the responsibilities of federal and state agencies for administering and supervising them, as well as the legal and political status of prisoners themselves.

In the United States, penal labor is a multi-billion-dollar industry. Annually, incarcerated workers provide at least $9 billion in services to the prison system and produce more than $2 billion in goods. The industry underwent many transitions throughout the late 19th and early and mid 20th centuries. Legislation such as the Hawes-Cooper Act of 1929 placed limitations on the trade of prison-made goods. Federal establishment of the Federal Prison Industries (FPI) in 1934 revitalized the prison labor system following the Great Depression. Increases in prison labor participation began in 1979 with the formation of the Prison Industry Enhancement Certification Program (PIECP). The PIECP is a federal program first authorized under the Justice System Improvement Act of 1979. Approved by Congress in 1990 for indefinite continuation, the program legalizes the transportation of prison-made goods across state lines and allows prison inmates to earn market wages in private sector jobs that can go towards tax deductions, victim compensation, family support, and room and board.

John Wallace Comer was a businessman, slave owner, mine operator and planter in Alabama during the Reconstruction Era and the early 1900s. The brother of Alabama Governor B. B. Comer, John Wallace Comer operated the Comer family plantation in Barbour County, Alabama. J. W. Comer served from 1863 until 1865 in the 57th Alabama Infantry Regiment during the American Civil War. J. W. Comer also operated the Eureka Iron Works throughout the late 1800s and early 1900s.

The history of forced labor in the United States encompasses to all forms of unfree labor which have occurred within the present day borders of the United States through the modern era. "Unfree labor" is a generic or collective term for those work relations, in which people are employed against their will by the threat of destitution, detention, violence, lawful compulsion, or other extreme hardship to themselves or to members of their families.

Martin Tabert was an American forced laborer. The circumstances of Tabert's death – being a white man beaten to death by an overseer – caused a public reaction that resulted eventually in the end of Florida’s longstanding convict leasing system. Convict leasing was one of the forms of legalized involuntary servitude common in the American South from the 1880s through the 1940s. Pursuant to Section 1 of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, slavery or involuntary servitude remains lawful as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted."

Knabb Turpentine was the name used for the pine resin harvesting and turpentine distilling businesses operated in northeast Florida by the Knabb brothers: Thomas Jefferson, William, and Earl, of Macclenny. Turpentine production boomed in North Florida between the late 1800s and 1920s; in the early 1900s, the Knabb family began to build one of the largest turpentine operations in the United States, and by the mid-20th century owned over 200,000 acres of pine forest in Baker County, over half its area. The eldest brother, T.J. Knabb (1880–1937), was the founder and president of the original Knabb Turpentine company. He made a fortune with the forced labor of jail inmates he leased from Baker, Alachua and Bradford counties, holding the convicts in peonage. Knabb was elected to the Florida Legislature in 1921 and served as a state senator of District 29 during the 1921, 1923, 1929 and 1931 legislative sessions. He was a co-founder of the Citizen's Bank of Macclenny and its vice-president until his death.

The Chattahoochee Brick Company was a brickworks located on the banks of the Chattahoochee River in Atlanta, Georgia, United States. The brickworks, founded by Atlanta mayor James W. English in 1878, is notable for its extensive use of convict lease labor, wherein hundreds of African American convicts worked in conditions similar to those experienced during antebellum slavery. It is speculated that some workers who died at the brickworks were buried on its grounds. The brickworks was discussed in Douglas A. Blackmon's Pulitzer Prize-winning book Slavery by Another Name, released in 2008. The property ceased to be an active brickworks in 2011.

Penitentiaries, Reformatories, and Chain Gangs: Social Theory and the History of Punishment in Nineteenth-Century America is a non-fiction book written by Mark Colvin. It was published by St. Martin's Press in 1997. In this book, Colvin applies theoretical perspectives to changes in punishment that occurred in the United States penal system during the 19th century.