Related Research Articles

Burrhus Frederic Skinner was an American psychologist, behaviorist, inventor, and social philosopher. Considered the father of Behaviorism, he was the Edgar Pierce Professor of Psychology at Harvard University from 1958 until his retirement in 1974.

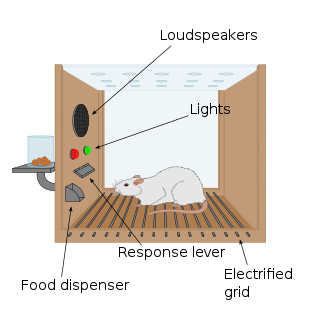

Operant conditioning, also called instrumental conditioning, is a learning process where voluntary behaviors are modified by association with the addition of reward or aversive stimuli. The frequency or duration of the behavior may increase through reinforcement or decrease through punishment or extinction.

In behavioral psychology, reinforcement is any consequence that increases the likelihood of an organism's future behavior whenever that behavior is preceded by a particular antecedent stimulus. For example, a rat can be trained to push a lever to receive food whenever a light is turned on. In this example, the light is the antecedent stimulus, the lever pushing is the behavior, and the food is the reinforcement. Likewise, a student that receives attention and praise when answering a teacher's question will be more likely to answer future questions in class. The teacher's question is the antecedent, the student's response is the behavior, and the praise and attention are the reinforcements.

Radical behaviorism is a "philosophy of the science of behavior" developed by B. F. Skinner. It refers to the philosophy behind behavior analysis, and is to be distinguished from methodological behaviorism—which has an intense emphasis on observable behaviors—by its inclusion of thinking, feeling, and other private events in the analysis of human and animal psychology. The research in behavior analysis is called the experimental analysis of behavior and the application of the field is called applied behavior analysis (ABA), which was originally termed "behavior modification."

Social learning is a theory of learning process social behavior which proposes that new behaviors can be acquired by observing and imitating others. It states that learning is a cognitive process that takes place in a social context and can occur purely through observation or direct instruction, even in the absence of motor reproduction or direct reinforcement. In addition to the observation of behavior, learning also occurs through the observation of rewards and punishments, a process known as vicarious reinforcement. When a particular behavior is rewarded regularly, it will most likely persist; conversely, if a particular behavior is constantly punished, it will most likely desist. The theory expands on traditional behavioral theories, in which behavior is governed solely by reinforcements, by placing emphasis on the important roles of various internal processes in the learning individual.

The experimental analysis of behavior is a science that studies the behavior of individuals across a variety of species. A key early scientist was B. F. Skinner who discovered operant behavior, reinforcers, secondary reinforcers, contingencies of reinforcement, stimulus control, shaping, intermittent schedules, discrimination, and generalization. A central method was the examination of functional relations between environment and behavior, as opposed to hypothetico-deductive learning theory that had grown up in the comparative psychology of the 1920–1950 period. Skinner's approach was characterized by observation of measurable behavior which could be predicted and controlled. It owed its early success to the effectiveness of Skinner's procedures of operant conditioning, both in the laboratory and in behavior therapy.

Behaviorism is a systematic approach to understand the behavior of humans and other animals. It assumes that behavior is either a reflex evoked by the pairing of certain antecedent stimuli in the environment, or a consequence of that individual's history, including especially reinforcement and punishment contingencies, together with the individual's current motivational state and controlling stimuli. Although behaviorists generally accept the important role of heredity in determining behavior, they focus primarily on environmental events. The cognitive revolution of the late 20th century largely replaced behaviorism as an explanatory theory with cognitive psychology, which unlike behaviorism examines internal mental states.

In psychology, aversives are unpleasant stimuli that induce changes in behavior via negative reinforcement or positive punishment. By applying an aversive immediately before or after a behavior the likelihood of the target behavior occurring in the future is reduced. Aversives can vary from being slightly unpleasant or irritating to physically, psychologically and/or emotionally damaging. It is not the level of unpleasantness or intention that defines something as an aversive, but rather the level of effectiveness the unpleasant event has on changing (decreasing) behavior.

Applied behavior analysis (ABA), also called behavioral engineering, is a psychological intervention that applies approaches based upon the principles of respondent and operant conditioning to change behavior of social significance. It is the applied form of behavior analysis; the other two forms are radical behaviorism and the experimental analysis of behavior.

Behaviour therapy or behavioural psychotherapy is a broad term referring to clinical psychotherapy that uses techniques derived from behaviourism and/or cognitive psychology. It looks at specific, learned behaviours and how the environment, or other people's mental states, influences those behaviours, and consists of techniques based on behaviorism's theory of learning: respondent or operant conditioning. Behaviourists who practice these techniques are either behaviour analysts or cognitive-behavioural therapists. They tend to look for treatment outcomes that are objectively measurable. Behaviour therapy does not involve one specific method, but it has a wide range of techniques that can be used to treat a person's psychological problems.

Behavior modification is a treatment approach that uses respondent and operant conditioning to change behavior. Based on methodological behaviorism, overt behavior is modified with (antecedent) stimulus control and consequences, including positive and negative reinforcement contingencies to increase desirable behavior, or administering positive and negative punishment and/or extinction to reduce problematic behavior. It also uses systematic desensitization and flooding to combat phobias.

Extinction is a behavioral phenomenon observed in both operantly conditioned and classically conditioned behavior, which manifests itself by fading of non-reinforced conditioned response over time. When operant behavior that has been previously reinforced no longer produces reinforcing consequences the behavior gradually stops occurring. In classical conditioning, when a conditioned stimulus is presented alone, so that it no longer predicts the coming of the unconditioned stimulus, conditioned responding gradually stops. For example, after Pavlov's dog was conditioned to salivate at the sound of a metronome, it eventually stopped salivating to the metronome after the metronome had been sounded repeatedly but no food came. Many anxiety disorders such as post traumatic stress disorder are believed to reflect, at least in part, a failure to extinguish conditioned fear.

An avoidance response is a response that prevents an aversive stimulus from occurring. It is a kind of negative reinforcement. An avoidance response is a behavior based on the concept that animals will avoid performing behaviors that result in an aversive outcome. This can involve learning through operant conditioning when it is used as a training technique. It is a reaction to undesirable sensations or feedback that leads to avoiding the behavior that is followed by this unpleasant or fear-inducing stimulus.

In operant conditioning, punishment is any change in a human or animal's surroundings which, occurring after a given behavior or response, reduces the likelihood of that behavior occurring again in the future. As with reinforcement, it is the behavior, not the human/animal, that is punished. Whether a change is or is not punishing is determined by its effect on the rate that the behavior occurs. This is called motivating operations (MO), because they alter the effectiveness of a stimulus. MO can be categorized in abolishing operations, decrease the effectiveness of the stimuli and establishing, increase the effectiveness of the stimuli. For example, a painful stimulus which would act as a punisher for most people may actually reinforce some behaviors of masochistic individuals.

Positive behavior support (PBS) uses tools from applied behaviour analysis and values of normalisation and social role valorisation theory to improve quality of life, usually in schools. PBS uses functional analysis to understand what maintains an individual's challenging behavior and how to support the individual to get these needs met in more appropriate way, instead of using 'challenging behaviours'. People's inappropriate behaviors are difficult to change because they are functional; they serve a purpose for them. These behaviors may be supported by reinforcement in the environment. People may inadvertently reinforce undesired behaviors by providing objects and/or attention because of the behavior.

The professional practice of behavior analysis is a domain of behavior analysis, the others being radical behaviorism, experimental analysis of behavior and applied behavior analysis. The practice of behavior analysis is the delivery of interventions to consumers that are guided by the principles of radical behaviorism and the research of both experimental and applied behavior analysis. Professional practice seeks to change specific behavior through the implementation of these principles. In many states, practicing behavior analysts hold a license, certificate, or registration. In other states, there are no laws governing their practice and, as such, the practice may be prohibited as falling under the practice definition of other mental health professionals. This is rapidly changing as behavior analysts are becoming more and more common.

Behavior management, similar to behavior modification, is a less-intensive form of behavior therapy. Unlike behavior modification, which focuses on changing behavior, behavior management focuses on maintaining positive habits and behaviors and reducing negative ones. Behavior management skills are especially useful for teachers and educators, healthcare workers, and those working in supported living communities. This form of management aims to help professionals oversee and guide behavior management in individuals and groups toward fulfilling, productive, and socially acceptable behaviors. Behavior management can be accomplished through modeling, rewards, or punishment.

The behavioral analysis of child development originates from John B. Watson's behaviorism.

Tact is a term that B.F. Skinner used to describe a verbal operant which is controlled by a nonverbal stimulus and is maintained by nonspecific social reinforcement (praise).

Functional behavior assessment (FBA) is an ongoing process of collecting information with a goal of identifying the environmental variables that control a problem or target behavior. The purpose of the assessment is to prove and aid the effectiveness of the interventions or treatments used to help eliminate the problem behavior. Through functional behavior assessments, we have learned that there are complex patterns to people's seemingly unproductive behaviors. It is important to not only pay attention to consequences that follow the behavior but also the antecedent that evokes the behavior. More work needs to be done in the future with functional assessment including balancing precision and efficiency, being more specific with variables involved and a more smooth transition from assessment to intervention.

References

- ↑ Carey, T. A. (2005). "Countercontrol: What Do The Children Say?". School Psychology International. 26 (5): 595. doi:10.1177/0143034305060801. S2CID 220397866.

- ↑ O'Donohue, William; Ferguson, Kyle (2001). The Psychology of B. F. Skinner. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. p. 213. ISBN 978-0761917588.

- ↑ Segall, Marshall (2016). Human Behavior and Public Policy: A Political Psychology. New York: Pergamon Press Inc. pp. 36. ISBN 978-0080170879.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Seay, Mary; Robert Suppa; Sharon Schoen; Suzanne Roberts (January 1984). "Countercontrol: An issue in intervention". Remedial and Special Education. 5: 38. doi:10.1177/074193258400500108. S2CID 220539918.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Delprato, DJ (2002). "Countercontrol in behavior analysis". The Behavior Analyst. 25 (2): 191–200. doi:10.1007/BF03392057. PMC 2731607 . PMID 22478386.

- ↑ Baldwin, Steve; Barker, Philip (1991). Ethical Issues in Mental Health. Dordrecht: Springer Science+Business Media, B.V. p. 149. ISBN 9780412329500.

- ↑ Michael, J. (1982). "Distinguishing between discriminative and motivational functions of stimuli". Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1. 37 (1): 149–55. doi:10.1901/jeab.1982.37-149. PMC 1333126 . PMID 7057126.

- ↑ Michael, J. (1993). "Establishing operations". The Behavior Analyst. 16 (2): 191–206. doi:10.1007/BF03392623. PMC 2733648 . PMID 22478146.

- ↑ Carey, Timothy A.; Bourbon, W. Thomas (September 2006). "Is Countercontrol the Key to Understanding Chronic Behavior Problems?". Intervention in School and Clinic. 42 (1): 5–13. doi:10.1177/10534512060420010201. S2CID 144081996.

- 1 2 "Countercontrol: A New Look at Some Old Problems by Carey, Timothy A.; Bourbon, W. Thomas" . Retrieved 28 September 2011.