The prison-industrial complex (PIC) is a term, coined after the "military-industrial complex" of the 1950s, used by scholars and activists to describe the many relationships between institutions of imprisonment and the various businesses that benefit from them.

The prison abolition movement is a network of groups and activists that seek to reduce or eliminate prisons and the prison system, and replace them with systems of rehabilitation and education that do not place a focus on punishment and government institutionalization. The prison abolitionist movement is distinct from conventional prison reform, which is the attempt to improve conditions inside prisons.

The rights of civilian and military prisoners are governed by both national and international law. International conventions include the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; the United Nations' Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

The Ella Baker Center for Human Rights is a non-profit strategy and action center based in Oakland, California. The stated aim of the center is to work for justice, opportunity and peace in urban America. It is named for Ella Baker, a twentieth-century activist and civil rights leader originally from Virginia and North Carolina.

INCITE! Women, Gender Non-Conforming, and Trans people of Color Against Violence, formerly known as INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence, is a United States-based national activist organization of radical feminists of color advancing a movement to end violence against women of color and their communities. INCITE! is organized by a national collective of women of color and has active chapters and affiliates in San Francisco, Washington, D.C., Denver, Albuquerque, Austin, New Orleans, Boston, Philadelphia, New York City, Ann Arbor, Binghamton, Chicago, and a chapter in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. INCITE! was founded in 2000.

Coalition for Effective Public Safety (CEPS) is a California-based criminal justice reform coalition of approximately 40 organizations united behind specific principles aimed at increasing public safety in California while curtailing the reliance upon costly, ineffective practices such as mass incarceration.

Linda Sue Evans is an American radical leftist, who was convicted in connection with violent and deadly militant activities committed as part of her goal to free African-Americans from white oppression. Evans was sentenced in 1987 to 40 years in prison for using false identification to buy firearms and for harboring a fugitive in the 1981 Brinks armored truck robbery, in which two police officers and a guard were killed, and Black Liberation Army members were wounded. In a second case, she was sentenced in 1990 to five years in prison for conspiracy and malicious destruction in connection with eight bombings including the 1983 United States Senate bombing. Her sentence was commuted in 2001 by President Bill Clinton because of its extraordinary length.

A prison, also known as a jail, gaolpenitentiary, detention center, correction center, correctional facility, or remand center, is a facility where people are confined against their will and denied a variety of freedoms under the authority of the state, generally as punishment for various crimes. Authorities most commonly use prisons within a criminal-justice system: people charged with crimes may be imprisoned until their trial; those who have pled or been found guilty of crimes at trial may be sentenced to a specified period of imprisonment.

Penal labor in the United States is explicitly allowed by the 13th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution: "Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction." Unconvicted detainees awaiting trial cannot be forced to participate in labor programs in prison as this would violate the Thirteenth Amendment.

Ruth Wilson Gilmore is a prison abolitionist and prison scholar. She is the Director of the Center for Place, Culture, and Politics and professor of geography in Earth and Environmental Sciences at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. She has been credited with "more or less single-handedly" inventing carceral geography, the "study of the interrelationships across space, institutions and political economy that shape and define modern incarceration". She received the 2020 Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Association of Geographers.

Gender-responsive prisons are prisons constructed to provide gender-specific care to incarcerated women. Contemporary sex-based prison programs were presented as a solution to the rapidly increasing number of women in the prison industrial complex and the overcrowding of California's prisons. These programs vary in intent and implementation and are based on the idea that female offenders differ from their male counterparts in their personal histories and pathways to crime. Multi-dimensional programs oriented toward female behaviors are considered by many to be effective in curbing recidivism.

The No New SF Jail Coalition is a group whose goals were initially to stop the construction of a $290 million prison at 850 Bryant St. The Coalition consists of "advocates for housing justice, formerly imprisoned people, transgender communities, architects and planners, children of imprisoned people, and concerned residents." The group worked closely with the organization Critical Resistance to see their plans come into action. The proposal by San Francisco Sheriff Ross Mirkarimi was to construct a new $290 million jail in SF. The No New SF Jail Coalition fought against this proposal advocating that the current system was only at 65% capacity, population in SF jails was decreasing, and that prisoners were reporting abuse by the sheriff's deputies. The key goals of the Coalition were to prevent the expansion of jails in San Francisco, as the construction of a new jail would do nothing to combat the real issue of mass incarceration. The campaign began in 2013 and after two years of work in December 2015, the Coalition was victorious in its efforts. The San Francisco Board of Supervisors voted against allocating the money towards the project. Board President London Breed advocated for the cause, believing that instead of building new jails the city needs to focus on putting money towards programs that address mental health and addiction. As a result, the Coalition was successful in its organizing and advocacy towards prison and jail abolition.

The California Prison Moratorium Project is a grassroots organization co-founded by Dr. Ruth Gilmore, involved in Prison Abolition through Critical Resistance, and Ernesto Saveedra, a youth advocate, for the purpose of stopping "all public and private prison construction in California." Over its activist life, the CPMP has partnered with a number of groups including Critical Resistance, The California Coalition for Women Prisoners, Californians United for a Responsible Budget (CURB), and many other abolitionist organizations to move forward in their goal of halting any erection of additional penal facilities within the state of California. An example of their collective success is demonstrated in such cases as the 2001 prevention of a new Delano Prison where anti-prison activists such as the CPMP swayed public opinion away from yet another jail.

Susan Burton is an activist based in Los Angeles, United States who works with formerly incarcerated people and founded the nonprofit organization, A New Way of Life. She was named a CNN Hero in 2010 and a Purpose Prize winner in 2012.

Mariame Kaba is an American activist, grassroots organizer, and educator who advocates for the abolition of the prison industrial complex, including all police. She is the author of We Do This 'Til We Free Us (2021). The Mariame Kaba Papers are held by the Chicago Public Library Special Collections.

Carceral feminism is a critical term for types of feminism that advocate for enhancing and increasing prison sentences that deal with feminist and gender issues. The term criticises the belief that harsher and longer prison sentences will help work towards solving these issues. The phrase "carceral feminism" was coined by Elizabeth Bernstein, a feminist sociologist, in her 2007 article, "The Sexual Politics of the 'New Abolitionism'". Examining the contemporary anti-trafficking movement in the United States, Bernstein introduced the term to describe a type of feminist activism which casts all forms of sexual labor as sex trafficking. She sees this as a retrograde step, suggesting it erodes the rights of women in the sex industry, and takes the focus off other important feminist issues, and expands the neoliberal agenda.

Janetta Louise Johnson is an American transgender rights activist, human rights activist, prison abolitionist, and transgender woman. She is the Executive Director of the TGI Justice Project. She co-founded the non-profit TAJA's Coalition in 2015. Along with Honey Mahogany and Aria Sa'id, Johnson is a co-founder of The Transgender District, established in 2017. Johnson's work is primarily concerned about the rights and safety of incarcerated and formerly-incarcerated transgender and gender-non-conforming people. She believes that the abolition of police and the prison industrial complex will help support the safety of transgender people, and she identifies as an abolitionist.

Decarceration in the United States involves government policies and community campaigns aimed at reducing the number of people held in custody or custodial supervision. Decarceration, the opposite of incarceration, also entails reducing the rate of imprisonment at the federal, state and municipal level. As of 2019, the US was home to 5% of the global population but 25% of its prisoners. Until the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. possessed the world's highest incarceration rate: 655 inmates for every 100,000 people, enough inmates to equal the populations of Philadelphia or Houston. The COVID-19 pandemic has reinvigorated the discussion surrounding decarceration as the spread of the virus poses a threat to the health of those incarcerated in prisons and detention centers where the ability to properly socially distance is limited. As a result of the push for decarceration in the wake of the pandemic, as of 2022, the incarceration rate in the United States declined to 505 per 100,000, resulting in the United States no longer having the highest incarceration rate in the world, but still remaining in the top five.

Liat Ben-Moshe is a disability scholar and assistant professor of criminology, Law, and Justice at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Ben-Moshe holds a PhD in sociology from Syracuse University with concentrations in Women and Gender Studies and Disability Studies. Ben-Moshe's work “has brought an intersectional disability studies approach to the phenomenon of mass incarceration and decarceration in the US”. Ben-Moshe's major works include Building Pedagogical Curb Cuts: Incorporating Disability into the University Classroom and Curriculum (2005), Disability Incarcerated: Imprisonment and Disability in the United States and Canada (2014), and Decarcerating Disability: Deinstitutionalization and Prison Abolition (2020). Ben-Moshe is best known for her theories of dis-epistemology, genealogy of deinstitutionalization, and race-ability.

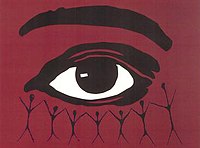

Ashley Hunt is an American artist, activist, writer and educator, primarily known for his photographic and video works on the American prison system, mass incarceration and the prison abolition movement. He is currently a faculty member of the School of Art at the California Institute of the Arts.