Related Research Articles

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people in whole or in part.

Cultural genocide or culturicide is a concept described by Polish lawyer Raphael Lemkin in 1944, in the same book that coined the term genocide. The destruction of culture was a central component in Lemkin's formulation of genocide. Though the precise definition of cultural genocide remains contested, the Armenian Genocide Museum defines it as "acts and measures undertaken to destroy nations' or ethnic groups' culture through spiritual, national, and cultural destruction". The drafters of the 1948 Genocide Convention initially considered using the term, but later dropped it from inclusion.

Ethnocide is the extermination or destruction of cultures.

Frybread is a dish of the indigenous people of North America that is a flat dough bread, fried or deep-fried in oil, shortening, or lard.

Native American studies is an interdisciplinary academic field that examines the history, culture, politics, issues, spirituality, sociology and contemporary experience of Native peoples in North America, or, taking a hemispheric approach, the Americas. Increasingly, debate has focused on the differences rather than the similarities between other Ethnic studies disciplines such as African American studies, Asian American Studies, and Latino/a Studies.

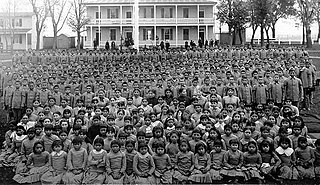

Kill the Indian, Save the Man: The Genocidal Impact of American Indian Residential Schools is a 2004 book by the American writer Ward Churchill, then a professor at the University of Colorado Boulder and an activist in Native American issues. Beginning in the late 19th century, it traces the history of the United States and Canadian governments establishing Indian boarding schools or residential schools, respectively, where Native American children were required to attend, to encourage their study of English, conversion to Christianity, and assimilation to the majority culture. The boarding schools were operated into the 1980s. Because the schools often prohibited students from using their Native languages and practicing their own cultures, Churchill considers them to have been genocidal in intent.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada was a truth and reconciliation commission active in Canada from 2008 to 2015, organized by the parties of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement.

American Indian boarding schools, also known more recently as American Indian residential schools, were established in the United States from the mid-17th to the early 20th centuries with a primary objective of "civilizing" or assimilating Native American children and youth into Anglo-American culture. In the process, these schools denigrated Native American culture and made children give up their languages and religion. At the same time the schools provided a basic Western education. These boarding schools were first established by Christian missionaries of various denominations. The missionaries were often approved by the federal government to start both missions and schools on reservations, especially in the lightly populated areas of the West. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries especially, the government paid religious orders to provide basic education to Native American children on reservations, and later established its own schools on reservations. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) also founded additional off-reservation boarding schools based on the assimilation model. These sometimes drew children from a variety of tribes. In addition, religious orders established off-reservation schools.

A Little Matter of Genocide: Holocaust and Denial in the Americas 1492 to the Present (1997) is a book which was written by Ward Churchill. A Little Matter of Genocide surveys ethnic cleansing from 1492 to the present. Churchill compares the treatment of North American Indians to historical instances of genocide by communists in Cambodia, Turks against Armenians, and Europeans against the Gypsies, as well as Nazis against the Poles and Jews.

The Indian Relocation Act of 1956 was a United States law intended to create a "a program of vocational training" for Native Americans in the United States. Critics characterize the law as an attempt to encourage Native Americans to leave Indian reservations and their traditional lands, to assimilate into the general population in urban areas, and to weaken community and tribal ties. Critics also characterize the law as part of the Indian termination policy between 1940 and 1960, which terminated the tribal status of numerous groups and cut off previous assistance to tribal citizens. The Indian Relocation Act encouraged and forced Native Americans to move to cities for job opportunities. It also played a significant role in increasing the population of urban Native Americans in succeeding decades.

Historical trauma (HT), as used by psychotherapists, social workers, historians, and psychologists, refers to the cumulative emotional harm of an individual or generation caused by a traumatic experience or event. Historical Trauma Response (HTR) refers to the manifestation of emotions and actions that stem from this perceived trauma.

Indigenous peoples of California, commonly known as Indigenous Californians or Native Californians, are a diverse group of nations and peoples that are indigenous to the geographic area within the current boundaries of California before and after European colonization. There are currently 109 federally recognized tribes in the state and over forty self-identified tribes or tribal bands that have applied for federal recognition. California has the second-largest Native American population in the United States.

The genocide of Indigenous peoples, colonial genocide, or settler genocide is the intentional elimination of Indigenous peoples as a part of the process of colonialism.

The effects of genocide on youth include psychological and demographic effects that affect the transition into adulthood. These effects are also seen in future generations of youth.

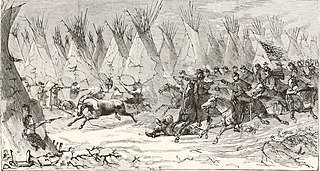

The California genocide was a series of systematized killings of thousands of Indigenous peoples of California by United States government agents and private citizens in the 19th century. It began following the American Conquest of California from Mexico, and the influx of settlers due to the California Gold Rush, which accelerated the decline of the Indigenous population of California. Between 1846 and 1873, it is estimated that non-Natives killed between 9,492 and 16,094 California Natives. Hundreds to thousands were additionally starved or worked to death. Acts of enslavement, kidnapping, rape, child separation and forced displacement were widespread. These acts were encouraged, tolerated, and carried out by state authorities and militias.

Settler colonialism in Canada is the continuation and the results of the colonization of the assets of the Indigenous peoples in Canada. As colonization progressed, the Indigenous peoples were subject to policies of forced assimilation and cultural genocide. The policies signed many of which were designed to both allowed stable houses. Governments in Canada in many cases ignored or chose to deny the aboriginal title of the First Nations. The traditional governance of many of the First Nations was replaced with government-imposed structures. Many of the Indigenous cultural practices were banned. First Nation's people status and rights were less than that of settlers. The impact of colonization on Canada can be seen in its culture, history, politics, laws, and legislatures.

The connection between colonialism and genocide has been explored in academic research. According to historian Patrick Wolfe, "[t]he question of genocide is never far from discussions of settler colonialism." Historians have commented that although colonialism does not necessarily directly involve genocide, research suggests that the two share a connection.

Denial of genocides of Indigenous peoples consists of a claim that has denied any of the multiple genocides and atrocity crimes, which have been committed against Indigenous peoples. The denialism claim contradicts the academic consensus, which acknowledges that genocide was committed. The claim is a form of denialism, genocide denial, historical negationism and historical revisionism. The atrocity crimes include genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and ethnic cleansing.

Indigenous response to colonialism has varied depending on the Indigenous group, historical period, territory, and colonial state(s) they have interacted with. Indigenous peoples have had agency in their response to colonialism. They have employed armed resistance, diplomacy, and legal procedures. Others have fled to inhospitable, undesirable or remote territories to avoid conflict. Nevertheless, some Indigenous peoples were forced to move to reservations or reductions, and work in mines, plantations, construction, and domestic tasks. They have detribalized and culturally assimilated into colonial societies. On occasion, Indigenous peoples have formed alliances with one or more Indigenous or non-Indigenous nations. Overall, the response of Indigenous peoples to colonialism during this period has been diverse and varied in its effectiveness. Indigenous resistance has a centuries-long history that is complex and carries on into contemporary times.

Native American genocide in the United States refers to the characterization of the substantial population decline of American Indians as a form of genocide. The question of whether the significant population decline constitutes genocide is debated amongst scholars. Debates are ongoing over whether the entire process, or specific periods and local occurrences, meet the legal definition of genocide. Raphael Lemkin, who coined the term "genocide," considered the colonial displacement of Native Americans by English and later British settlers as a historical example of genocide. However, others, like historian Gary Anderson, contend that genocide does not accurately characterize any aspect of American history, suggesting instead that ethnic cleansing is a more appropriate term.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mako, Shamiran (18 June 2012). "Cultural Genocide and Key International Instruments: Framing the Indigenous Experience". International Journal on Minority and Group Rights. Social Science Research Network. 19 (2): 175–194. doi:10.1163/157181112X639078. SSRN 2087175 . Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- 1 2 "'Still experiencing a cultural genocide'". BBC News. 12 May 2016. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ↑ Ross, Luana (1996). "Resistance and Survivance: Cultural Genocide and Imprisoned Native Women". Race, Gender & Class. 3 (2): 125–141. ISSN 1082-8354. JSTOR 41674793 . Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ↑ Bachman, Jeffrey S. (22 November 2017). The United States and Genocide: (Re)Defining the Relationship. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-69216-8 . Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- 1 2 3 Ibrahim, Azeem; Prey, Emily. "The United States Must Reckon With Its Own Genocides". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 25 February 2022.