Related Research Articles

A galaxy is a system of stars, stellar remnants, interstellar gas, dust, and dark matter bound together by gravity. The word is derived from the Greek galaxias (γαλαξίας), literally 'milky', a reference to the Milky Way galaxy that contains the Solar System. Galaxies, averaging an estimated 100 million stars, range in size from dwarfs with less than a thousand stars, to the largest galaxies known – supergiants with one hundred trillion stars, each orbiting its galaxy's center of mass. Most of the mass in a typical galaxy is in the form of dark matter, with only a few percent of that mass visible in the form of stars and nebulae. Supermassive black holes are a common feature at the centres of galaxies.

A molecular cloud, sometimes called a stellar nursery (if star formation is occurring within), is a type of interstellar cloud, the density and size of which permit absorption nebulae, the formation of molecules (most commonly molecular hydrogen, H2), and the formation of H II regions. This is in contrast to other areas of the interstellar medium that contain predominantly ionized gas.

A quasar is an extremely luminous active galactic nucleus (AGN). It is sometimes known as a quasi-stellar object, abbreviated QSO. The emission from an AGN is powered by a supermassive black hole with a mass ranging from millions to tens of billions of solar masses, surrounded by a gaseous accretion disc. Gas in the disc falling towards the black hole heats up and releases energy in the form of electromagnetic radiation. The radiant energy of quasars is enormous; the most powerful quasars have luminosities thousands of times greater than that of a galaxy such as the Milky Way. Quasars are usually categorized as a subclass of the more general category of AGN. The redshifts of quasars are of cosmological origin.

The Andromeda Galaxy is a barred spiral galaxy and is the nearest major galaxy to the Milky Way. It was originally named the Andromeda Nebula and is cataloged as Messier 31, M31, and NGC 224. Andromeda has a diameter of about 46.56 kiloparsecs and is approximately 765 kpc from Earth. The galaxy's name stems from the area of Earth's sky in which it appears, the constellation of Andromeda, which itself is named after the princess who was the wife of Perseus in Greek mythology.

The Triangulum Galaxy is a spiral galaxy 2.73 million light-years (ly) from Earth in the constellation Triangulum. It is catalogued as Messier 33 or NGC (New General Catalogue) 598. With the D25 isophotal diameter of 18.74 kiloparsecs (61,100 light-years), the Triangulum Galaxy is the third-largest member of the Local Group of galaxies, behind the Andromeda Galaxy and the Milky Way.

Messier 87 is a supergiant elliptical galaxy in the constellation Virgo that contains several trillion stars. One of the largest and most massive galaxies in the local universe, it has a large population of globular clusters—about 15,000 compared with the 150–200 orbiting the Milky Way—and a jet of energetic plasma that originates at the core and extends at least 1,500 parsecs, traveling at a relativistic speed. It is one of the brightest radio sources in the sky and a popular target for both amateur and professional astronomers.

A supermassive black hole is the largest type of black hole, with its mass being on the order of hundreds of thousands, or millions to billions, of times the mass of the Sun (M☉). Black holes are a class of astronomical objects that have undergone gravitational collapse, leaving behind spheroidal regions of space from which nothing can escape, not even light. Observational evidence indicates that almost every large galaxy has a supermassive black hole at its center. For example, the Milky Way galaxy has a supermassive black hole at its center, corresponding to the radio source Sagittarius A*. Accretion of interstellar gas onto supermassive black holes is the process responsible for powering active galactic nuclei (AGNs) and quasars.

In 1944, Walter Baade categorized groups of stars within the Milky Way into stellar populations. In the abstract of the article by Baade, he recognizes that Jan Oort originally conceived this type of classification in 1926.

In physical cosmology, a protogalaxy, which could also be called a "primeval galaxy", is a cloud of gas which is forming into a galaxy. It is believed that the rate of star formation during this period of galactic evolution will determine whether a galaxy is a spiral or elliptical galaxy; a slower star formation tends to produce a spiral galaxy. The smaller clumps of gas in a protogalaxy form into stars.

In the fields of Big Bang theory and cosmology, reionization is the process that caused electrically neutral atoms in the universe to reionize after the lapse of the "dark ages".

The Sloan Digital Sky Survey or SDSS is a major multi-spectral imaging and spectroscopic redshift survey using a dedicated 2.5-m wide-angle optical telescope at Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico, United States. The project began in 2000 and was named after the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, which contributed significant funding.

A dwarf galaxy is a small galaxy composed of about 1000 up to several billion stars, as compared to the Milky Way's 200–400 billion stars. The Large Magellanic Cloud, which closely orbits the Milky Way and contains over 30 billion stars, is sometimes classified as a dwarf galaxy; others consider it a full-fledged galaxy. Dwarf galaxies' formation and activity are thought to be heavily influenced by interactions with larger galaxies. Astronomers identify numerous types of dwarf galaxies, based on their shape and composition.

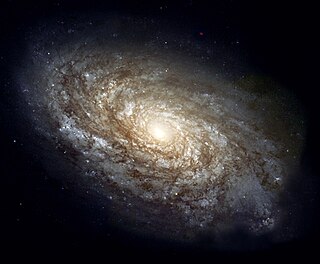

Messier 94 is a spiral galaxy in the mid-northern constellation Canes Venatici. It was discovered by Pierre Méchain in 1781, and catalogued by Charles Messier two days later. Although some references describe M94 as a barred spiral galaxy, the "bar" structure appears to be more oval-shaped. The galaxy has two ring structures.

VIRGOHI21 is an extended region of neutral hydrogen (HI) in the Virgo cluster discovered in 2005. Analysis of its internal motion indicates that it may contain a large amount of dark matter, as much as a small galaxy. Since VIRGOHI21 apparently contains no stars, this would make it one of the first detected dark galaxies. Skeptics of this interpretation argue that VIRGOHI21 is simply a tidal tail of the nearby galaxy NGC 4254.

The Milky Way is the galaxy that includes the Solar System, with the name describing the galaxy's appearance from Earth: a hazy band of light seen in the night sky formed from stars that cannot be individually distinguished by the naked eye. The term Milky Way is a translation of the Latin via lactea, from the Greek γαλαξίας κύκλος, meaning "milky circle". From Earth, the Milky Way appears as a band because its disk-shaped structure is viewed from within. Galileo Galilei first resolved the band of light into individual stars with his telescope in 1610. Until the early 1920s, most astronomers thought that the Milky Way contained all the stars in the Universe. Following the 1920 Great Debate between the astronomers Harlow Shapley and Heber Doust Curtis, observations by Edwin Hubble showed that the Milky Way is just one of many galaxies.

The Milky Way has several smaller galaxies gravitationally bound to it, as part of the Milky Way subgroup, which is part of the local galaxy cluster, the Local Group.

The Andromeda–Milky Way collision is a galactic collision predicted to occur in about 4.5 billion years between the two largest galaxies in the Local Group—the Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy. The stars involved are sufficiently far apart that it is improbable that any of them will individually collide, though some stars will be ejected.

Galaxy mergers can occur when two galaxies collide. They are the most violent type of galaxy interaction. The gravitational interactions between galaxies and the friction between the gas and dust have major effects on the galaxies involved. The exact effects of such mergers depend on a wide variety of parameters such as collision angles, speeds, and relative size/composition, and are currently an extremely active area of research. Galaxy mergers are important because the merger rate is a fundamental measurement of galaxy evolution. The merger rate also provides astronomers with clues about how galaxies bulked up over time.

Smith's Cloud is a high-velocity cloud of hydrogen gas located in the constellation Aquila at Galactic coordinates l = 39°, b = −13°. The cloud was discovered in 1963 by Gail Bieger, née Smith, who was an astronomy student at Leiden University in the Netherlands.

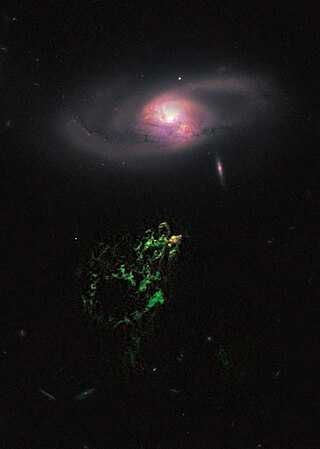

Hanny's Voorwerp, is a type of astronomical object called a quasar ionization echo. It was discovered in 2007 by Dutch schoolteacher Hanny van Arkel while she was participating as a volunteer in the Galaxy Zoo project, part of the Zooniverse group of citizen science websites. Photographically, it appears as a bright blob close to spiral galaxy IC 2497 in the constellation Leo Minor.

References

- ↑ "First evidence of dark galaxies from the early Universe spotted". Zmescience.com. 2012-07-11. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- ↑ Cannon, John M.; Martinkus, Charlotte P.; Leisman, Lukas; Haynes, Martha P.; Adams, Elizabeth A. K.; Giovanelli, Riccardo; Hallenbeck, Gregory; Janowiecki, Steven; Jones, Michael (2015-02-01). "The Alfalfa "Almost Darks" Campaign: Pilot VLA HI Observations of Five High Mass-To-Light Ratio Systems". The Astronomical Journal. 149 (2): 72. arXiv: 1412.3018 . Bibcode:2015AJ....149...72C. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/149/2/72. ISSN 0004-6256. S2CID 118592858.

- ↑ Oosterloo, T. A.; Heald, G. H.; De Blok, W. J. G. (2013). "Is GBT 1355+5439 a dark galaxy?". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 555: L7. arXiv: 1306.6148 . Bibcode:2013A&A...555L...7O. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201321965. S2CID 118402005.

- ↑ "The Arecibo Legacy Fast ALFA Survey". egg.astro.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2015-09-29.

- ↑ Janowiecki, Steven; Leisman, Lukas; Józsa, Gyula; Salzer, John J.; Haynes, Martha P.; Giovanelli, Riccardo; Rhode, Katherine L.; Cannon, John M.; Adams, Elizabeth A. K. (2015-03-01). "(Almost) Dark HI Sources in the ALFALFA Survey: The Intriguing Case of HI1232+20". The Astrophysical Journal. 801 (2): 96. arXiv: 1502.01296 . Bibcode:2015ApJ...801...96J. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/801/2/96. ISSN 0004-637X. S2CID 119271121.

- ↑ Van Dokkum, Pieter; et al. (25 August 2016). "A High Stellar Velocity Dispersion and ~100 Globular Clusters For The Ultra-Diffuse Galaxy Dragonfly 44". The Astrophysical Journal Letters . 828 (1): L6. arXiv: 1606.06291 . Bibcode:2016ApJ...828L...6V. doi: 10.3847/2041-8205/828/1/L6 . S2CID 1275440.

- ↑ Hall, Shannon (25 August 2016). "Ghost galaxy is 99.99 per cent dark matter with almost no stars". New Scientist . Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ↑ Feltman, Rachael (26 August 2016). "A new class of galaxy has been discovered, one made almost entirely of dark matter". The Washington Post . Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ↑ "The existence and detection of optically dark galaxies by 21-cm surveys". academic.oup.com. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.10247.x . Retrieved 2024-03-12.

- 1 2 Fraser Cain (2007-06-14). "No Stars Shine in This Dark Galaxy". Universetoday.com. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- ↑ "Arecibo Survey Produces Dark Galaxy Candidate". Spacedaily.com. 2006-04-07. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- 1 2 Stuart Clark. "Dark galaxy' continues to puzzle astronomers". New Scientist . Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- 1 2 "First Direct Detection Sheds Light On Dark Galaxies". Zmescience.com. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ↑ "Mysterious Dark Galaxy Emits No Visible Light, Scientists Say". 10 February 2023.

- ↑ Magain P.; et al. (2005). "Discovery of a bright quasar without a massive host galaxy". Nature. 437 (7057): 381–4. arXiv: astro-ph/0509433 . Bibcode:2005Natur.437..381M. doi:10.1038/nature04013. PMID 16163349. S2CID 4303895.

- ↑ Merritt, David; et al. (2006). "The nature of the HE0450-2958 system". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society . 367 (4): 1746–1750. arXiv: astro-ph/0511315 . Bibcode:2006MNRAS.367.1746M. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.10093.x. S2CID 55834970.

- ↑ Kim, Minjin; Ho, Luis; Peng, Chien; Im, Myungshin (2007). "The Host Galaxy of the Quasar HE 0450-2958". The Astrophysical Journal. 658 (1): 107–113. arXiv: astro-ph/0611411 . Bibcode:2007ApJ...658..107K. doi:10.1086/510846. S2CID 14375599.

- ↑ Josh Simon (2005). "Dark Matter in Dwarf Galaxies: Observational Tests of the Cold Dark Matter Paradigm on Small Scales" (PDF): 4273. Bibcode:2005PhDT.........2S. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-09-13.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Battersby, Stephen (2003-10-20). "Astronomers find first 'dark galaxy'". New Scientist. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ↑ Overbye, Dennis (26 January 2024). "What Do You Call a Galaxy Without Stars? - To dark matter and dark energy, add dark galaxies — collections of stars so sparse and faint that they are all but invisible". The New York Times . Archived from the original on 26 January 2024.

- ↑ Malusky, Jill (2024-01-08). "Astronomers Accidentally Discover Dark Primordial Galaxy". Green Bank Observatory. Archived from the original on 2024-03-09. Retrieved 2024-03-10.

- ↑ "Astronomers discover new almost dark galaxy". Phys.org. Retrieved 2024-02-06.

- ↑ "Dark galaxy crashing into the Milky Way". New Scientist. No. 2735. 22 November 2009. Retrieved 2009-12-12.

- ↑ Clark, Stuart (2005-02-23). "Astronomers claim first 'dark galaxy' find". NewScientist.com news service. Retrieved 2006-10-26.

- ↑ Shiga, David (2005-02-26). "Ghostly Galaxy: Massive, dark cloud intrigues scientists". Science News Online. 167 (9): 131. doi:10.2307/4015891. JSTOR 4015891. Archived from the original on 2011-05-24. Retrieved 2008-09-14.

- ↑ Britt, Roy (2005-02-23). "First Invisible Galaxy Discovered in Cosmology Breakthrough". Space.com.

- ↑ Funkhouser, Scott (2005). "Testing MOND with VirgoHI21". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 364 (1): 237. arXiv: astro-ph/0503104 . Bibcode:2005MNRAS.364..237F. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2005.09565.x. S2CID 119368923.

- ↑ Kent, Brian R.; Giovanelli, Riccardo; Haynes, Martha P.; Saintonge, Amélie; Stierwalt, Sabrina; Balonek, Thomas; Brosch, Noah; Catinella, Barbara; Koopmann, Rebecca A. (2007-08-01). "Optically Unseen H I Detections toward the Virgo Cluster Detected in the Arecibo Legacy Fast ALFA Survey". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 665 (1): L15–L18. Bibcode:2007ApJ...665L..15K. doi: 10.1086/521100 . ISSN 0004-637X.

- ↑ Duc, Pierre-Alain; Bournaud, Frederic (2008-02-01). "Tidal Debris from High-Velocity Collisions as Fake Dark Galaxies: A Numerical Model of VIRGOHI 21". The Astrophysical Journal. 673 (2): 787–797. arXiv: 0710.3867 . Bibcode:2008ApJ...673..787D. doi:10.1086/524868. ISSN 0004-637X. S2CID 15348867.

- ↑ Haynes, Martha P.; Giovanelli, Riccardo; Kent, Brian R. (2007). "NGC 4254: An Act of Harassment Uncovered by the Arecibo Legacy Fast ALFA Survey". Astrophysical Journal . 665 (1): L19–22. arXiv: 0707.0113 . Bibcode:2007ApJ...665L..19H. doi:10.1086/521188. S2CID 12930657.