Related Research Articles

Constantine I, also known as Constantine the Great, was a Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337 and the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity. He played a pivotal role in elevating the status of Christianity in Rome, decriminalizing Christian practice and ceasing Christian persecution in a period referred to as the Constantinian shift. Constantine is also the originator of the religiopolitical ideology known as Constantinism, which epitomizes the unity of church and state, as opposed to separation of church and state. He founded the city of Constantinople and made it the capital of the Empire.

Lucius Caecilius FirmianussignoLactantius was an early Christian author who became an advisor to Roman emperor Constantine I, guiding his Christian religious policy in its initial stages of emergence, and a tutor to his son Crispus. His most important work is the Institutiones Divinae, an apologetic treatise intended to establish the reasonableness and truth of Christianity to pagan critics.

The Battle of the Milvian Bridge took place between the Roman Emperors Constantine I and Maxentius on 28 October 312 AD. It takes its name from the Milvian Bridge, an important route over the Tiber. Constantine won the battle and started on the path that led him to end the Tetrarchy and become the sole ruler of the Roman Empire. Maxentius drowned in the Tiber during the battle; his body was later taken from the river and decapitated, and his head was paraded through the streets of Rome on the day following the battle before being taken to Africa.

Galerius Valerius Maximianus was Roman emperor from 305 to 311. During his reign he campaigned, aided by Diocletian, against the Sasanian Empire, sacking their capital Ctesiphon in 299. He also campaigned across the Danube against the Carpi, defeating them in 297 and 300. Although he was a staunch opponent of Christianity, Galerius ended the Diocletianic Persecution when he issued the Edict of Toleration in Serdica (Sofia) in 311.

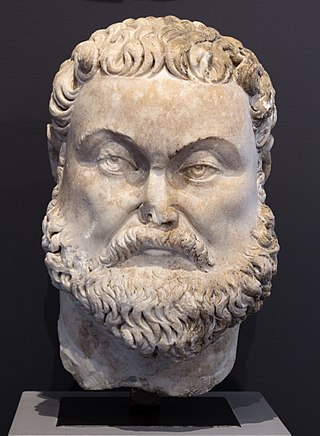

Maximian, nicknamed Herculius, was Roman emperor from 286 to 305. He was Caesar from 285 to 286, then Augustus from 286 to 305. He shared the latter title with his co-emperor and superior, Diocletian, whose political brain complemented Maximian's military brawn. Maximian established his residence at Trier but spent most of his time on campaign. In late 285, he suppressed rebels in Gaul known as the Bagaudae. From 285 to 288, he fought against Germanic tribes along the Rhine frontier. Together with Diocletian, he launched a scorched earth campaign deep into Alamannic territory in 288, refortifying the frontier.

Galerius Valerius Maximinus, born as Daza, was Roman emperor from 310 to 313. He became embroiled in the civil wars of the Tetrarchy between rival claimants for control of the empire, in which he was defeated by Licinius. A committed pagan, he engaged in one of the last persecutions of Christians, before issuing an edict of tolerance near his death.

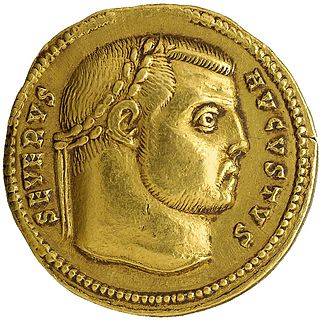

Flavius Valerius Severus, also called Severus II, was a Roman emperor from 306 to 307. After failing to besiege Rome, he fled to Ravenna. It is thought that he was killed there or executed near Rome.

The Edict of Milan was the February 313 AD agreement to treat Christians benevolently within the Roman Empire. Western Roman Emperor Constantine I and Emperor Licinius, who controlled the Balkans, met in Mediolanum and, among other things, agreed to change policies towards Christians following the edict of toleration issued by Emperor Galerius two years earlier in Serdica. The Edict of Milan gave Christianity legal status and a reprieve from persecution but did not make it the state church of the Roman Empire, which occurred in AD 380 with the Edict of Thessalonica.

Constantinian shift is used by some theologians and historians of antiquity to describe the political and theological changes that took place during the 4th-century under the leadership of Emperor Constantine the Great. Rodney Clapp claims that the shift or change started in the year 200. The term was popularized by the Mennonite theologian John H. Yoder. He claims that the change was not just freedom from persecution but an alliance between the State and the Church that led to a kind of Caesaropapism. The claim that there ever was a Constantinian shift has been disputed; Peter Leithart argues that there was a "brief, ambiguous 'Constantinian moment' in the fourth century", but that there was "no permanent, epochal 'Constantinian shift'".

"In hoc signo vinces" is a Latin phrase conventionally translated into English as "In this sign thou shalt conquer", often also being translated as "By this sign, conquer".

During the reign of the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great, Christianity began to transition to the dominant religion of the Roman Empire. Historians remain uncertain about Constantine's reasons for favoring Christianity, and theologians and historians have often argued about which form of early Christianity he subscribed to. There is no consensus among scholars as to whether he adopted his mother Helena's Christianity in his youth, or, as claimed by Eusebius of Caesarea, encouraged her to convert to the faith he had adopted.

The Diocletianic or Great Persecution was the last and most severe persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire. In 303, the emperors Diocletian, Maximian, Galerius, and Constantius issued a series of edicts rescinding Christians' legal rights and demanding that they comply with traditional religious practices. Later edicts targeted the clergy and demanded universal sacrifice, ordering all inhabitants to sacrifice to the gods. The persecution varied in intensity across the empire—weakest in Gaul and Britain, where only the first edict was applied, and strongest in the Eastern provinces. Persecutory laws were nullified by different emperors at different times, but Constantine and Licinius' Edict of Milan in 313 has traditionally marked the end of the persecution.

The Battle of Tzirallum was part of the civil wars of the Tetrarchy fought on 30 April 313 between the Roman armies of emperors Licinius and Maximinus. The battle location was on the "Campus Serenus" at Tzirallum, identified as the modern-day town of Çorlu, in Tekirdağ Province, in the Turkish region of Eastern Thrace. Sources put the battle between 18 and 36 Roman miles from Heraclea Perinthus, the modern-day town of Marmara Ereğlisi.

Prisca was a Roman empress as the wife of the emperor Diocletian.

The civil wars of the Tetrarchy were a series of conflicts between the co-emperors of the Roman Empire, starting from 306 AD with the usurpation of Maxentius and the defeat of Severus to the defeat of Licinius at the hands of Constantine I in 324 AD.

Sossianus Hierocles was a late Roman aristocrat and office-holder. He served as a praeses in Syria under Diocletian at some time in the 290s. He was then made vicarius of some district, perhaps Oriens until 303, when he was transferred to Bithynia. It is for his anti-Christian activities in Bithynia that he is principally remembered. He was, in the words of the Cambridge Ancient History, "one of the most zealous of persecutors". While in Bithynia, Hierocles authored Lover of Truth, a critique of Christianity. Lover of Truth is noted as the first instance of the trope, popular in later pagan polemic, of comparing the pagan holy man Apollonius of Tyana to Jesus Christ.

The German and Sarmatian campaigns of Constantine were fought by the Roman Emperor Constantine I against the neighbouring Germanic peoples, including the Franks, Alemanni and Goths, as well as the Sarmatian Iazyges, along the whole Roman northern defensive system to protect the empire's borders, between 306 and 336.

Flavius Severianus was the son of the Roman Emperor Flavius Valerius Severus.

Gaius Fufius Geminus was a Roman senator who lived during the Principate. He was ordinary consul in the year 29 with Lucius Rubellius Geminus as his colleague. Geminus was the son of Gaius Fufius Geminus.

Candidianus was the son of the Roman Emperor Galerius and adoptive son of Galeria Valeria, the wife of Galerius and daughter of Diocletian.

References

- ↑ Lactantius. Lord Hailes (transl.) (2021) On the Deaths of the Persecutors: A Translation of De Mortibus Persecutorum by Lucius Cæcilius Firmianus Lactantius Evolution Publishing, Merchantville, NJ ISBN 978-1-935228-20-2, p. 2

- ↑ Lactantius. On the Deaths of the Persecutors, p. 93.

- ↑ Lactantius. On the Deaths of the Persecutors, p. 75.

- ↑ Touber, Jetze. “Patristic Scholarship and Religious Contention, 1678-1716: The Rediscovery and Publication of Lactantius's ‘De Mortibus Persecutorum," with Special Focus on Gijsbert Cuper (1644-1716).” Church History and Religious Culture, vol. 96, no. 3, 2016, pp. 266–303., www.jstor.org/stable/43946151. Accessed 22 May 2021. p. 272.

- ↑ Lactantius. J. L Creed (transl.). De Mortibus Persecutorum. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984.

- ↑ Touber, Jetze. “Patristic Scholarship and Religious Contention, 1678-1716: The Rediscovery and Publication of Lactantius's ‘De Mortibus Persecutorum.” p. 276.

- ↑ Touber, Jetze. “Patristic Scholarship and Religious Contention, 1678-1716: The Rediscovery and Publication of Lactantius's ‘De Mortibus Persecutorum.” p. 277.

- ↑ Touber, Jetze. “Patristic Scholarship and Religious Contention, 1678-1716: The Rediscovery and Publication of Lactantius's ‘De Mortibus Persecutorum.” p. 274.

- ↑ Touber, Jetze. “Patristic Scholarship and Religious Contention, 1678-1716: The Rediscovery and Publication of Lactantius's ‘De Mortibus Persecutorum.” p. 279.

- ↑ Barnes, Timothy D. Constantine and Eusebius. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1981. p. 13.