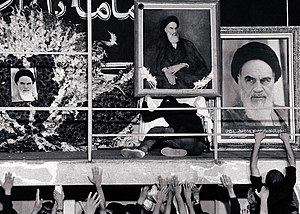

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini was an Iranian Islamic revolutionary, politician and religious leader who served as the first supreme leader of Iran from 1979 until his death in 1989. He was the founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran and the leader of the 1979 Iranian Revolution, which saw the overthrow of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and the end of the Iranian monarchy. Following the revolution, Khomeini became the country's first supreme leader, a position created in the constitution of the Islamic Republic as the highest-ranking political and religious authority of the nation, which he held until his death. Most of his period in power was taken up by the Iran–Iraq War of 1980–1988. He was succeeded by Ali Khamenei on 4 June 1989.

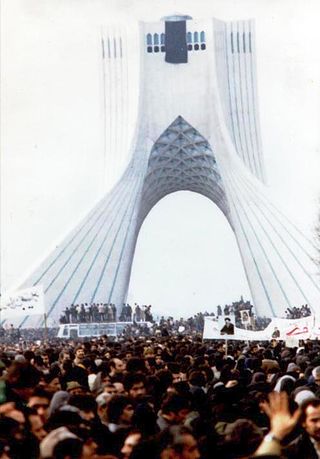

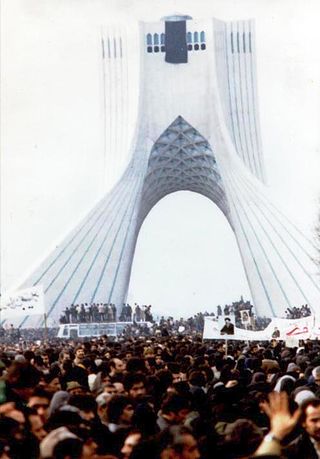

The Iranian Revolution, or the Islamic Revolution, was a series of events that culminated in the overthrow of the Pahlavi dynasty in 1979. The revolution also led to the replacement of the Imperial State of Iran by the present-day Islamic Republic of Iran, as the monarchical government of Mohammed Reza Pahlavi was superseded by the theocratic government of Ruhollah Khomeini, a religious cleric who had headed one of the rebel factions. The ousting of Pahlavi, the last Shah of Iran, formally marked the end of Iran's historical monarchy.

Slime, a German punk rock band founded in Hamburg in 1979, became a defining band in the 1980s German punk scene, and is the most widely recognized example of the musical style Deutschpunk.

Wir sind Helden was a German pop rock band that was established in 2000 in Hamburg and based in Berlin. The band was composed of lead singer and guitarist Judith Holofernes, drummer Pola Roy, bassist Mark Tavassol and keyboardist/guitarist Jean-Michel Tourette.

Naser al-Din Shah Qajar was the fourth Shah of Qajar Iran from 5 September 1848 to 1 May 1896 when he was assassinated. He was the son of Mohammad Shah Qajar and Malek Jahan Khanom and the third longest reigning monarch in Iranian history after Shapur II of the Sassanid dynasty and Tahmasp I of the Safavid dynasty. Nasser al-Din Shah had sovereign power for close to 51 years.

The Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist is a concept in Twelver Shia Islamic law which holds that until the reappearance of the "infallible Imam", at least some of the "religious and social affairs" of the Muslim world should be administered by righteous Shi'i jurists (Faqīh). Shia disagree over whose "religious and social affairs" are to be administered and what those affairs are.

Khomeinism refers to the religious and political ideas of the leader of the 1979 Iranian Islamic Revolution, Ruhollah Khomeini. Khomeinism may also refer to the ideology of the clerical class which has ruled Islamic Republic of Iran founded by Khomeini, after his death. It can also be used to refer to the radicalization of segments of the Twelver Shia populations of Iran, Iraq, and Lebanon, and the Iranian government's recruitment of Shia minorities in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and Africa. The word Khomeinist and Khomeinists, derived from Khomeinism, are also used to describe members of Iran's clerical rulers and differentiate them from regular Shia Muslim clerics.

Peter Roman Scholl-Latour was a French-German journalist, author and reporter.

Michael Kehlmann was an Austrian television film director and theatre director, screenwriter and actor.

Richard Wagner was a Romanian-born German novelist. He published a number of short stories, novels and essays.

Johann Sebastian Bach composed the church cantata Komm, du süße Todesstunde, BWV 161, in Weimar for the 16th Sunday after Trinity, probably first performed on 27 September 1716.

Friedrich Wilhelm Schulz was a German officer, political writer and radical liberal publisher in Hesse. His most famous works are Der Tod des Pfarrers Friedrich Ludwig Weidig as well as Die Bewegung der Produktion, which Karl Marx quoted extensively in his 1844 Manuscripts. Schulz was the first to describe the movement of society "as flowing from the contradiction between the forces of production and the mode of production," which would later form the basis of historical materialism. Marx continued to praise Schulz's work decades later when writing Das Kapital.

Gero von Boehm is a German director, journalist and television presenter.

The following is a timeline of the history of the city of Tehran, Iran.

Ruhollah Khomeini’s return to Iran on 1 February 1979, after 14 years in exile, was an important event in the Iranian Revolution. It led to the collapse of the provisional government of Shapour Bakhtiar and the final overthrow of the Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, on 11 February 1979.

The Leimbach Park is a linear park and 100-year flood prevention scheme opened in October 2016 in Wiesloch, Germany. It is part of a larger ecological enhancement of the River Leimbach. The park follows the River Leimbach downstream from Wiesloch to a larger 1.4-hectare (3.5-acre) area just north of Wiesloch-Walldorf station, part of the former Tonwaren-Industrie Wiesloch brickworks.

On 8 January 2017, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, the fourth President of Iran and the country's Chairman of Expediency Discernment Council, died at the age of 82 after suffering a heart attack. He was transferred unconscious to a hospital in Tajrish, north Tehran. Attempts at cardiopulmonary resuscitation for more than an hour trying to revive him were unsuccessful and he died at 19:30 local time (UTC+3:30).

Düzen Tekkal is a German author, television journalist, filmmaker, war correspondent, political scientist, and social entrepreneur of Kurdish–Yazidi descent.