Related Research Articles

Sojourner Truth was an American abolitionist and women's rights activist. Truth was born into slavery in Swartekill, New York, but escaped with her infant daughter to freedom in 1826. After going to court to recover her son in 1828, she became the first black woman to win such a case against a white man.

Slavery in the colonial history of the United States, from 1526 to 1776, developed from complex factors, and researchers have proposed several theories to explain the development of the institution of slavery and of the slave trade. Slavery strongly correlated with the European colonies' demand for labor, especially for the labor-intensive plantation economies of the sugar colonies in the Caribbean and South America, operated by Great Britain, France, Spain, Portugal and the Dutch Republic.

Slavery in the United States was the legal institution of human chattel slavery, comprising the enslavement primarily of Africans and African Americans, that existed in the United States of America from its founding in 1776 until the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865. Slavery was established throughout European colonization in the Americas. From early colonial days, it was practiced in Britain's colonies, including the Thirteen Colonies which formed the United States. Under the law, an enslaved person was treated as property and could be bought, sold, or given away. Slavery lasted in about half of U.S. states until 1865. As an economic system, slavery was largely replaced by sharecropping and convict leasing.

Geographically, the U.S. states known as the Old South are those in the Southern United States that were among the original Thirteen Colonies. The region term is differentiated from the Deep South and Upper South, by being limited to these states' present-day boundaries, rather than those of their colonial predecessors.

African-American history is a part of American history that looks at the history of African Americans or Black Americans in the country.

In the British colonies in North America and in the United States before the abolition of slavery in 1865, free Negro or free Black described the legal status of African Americans who were not enslaved. The term was applied both to formerly enslaved people (freedmen) and to those who had been born free.

Slavery in the British and French Caribbean refers to slavery in the parts of the Caribbean dominated by France or the British Empire.

Partus sequitur ventrem was a legal doctrine passed in colonial Virginia in 1662 and other English crown colonies in the Americas which defined the legal status of children born there; the doctrine mandated that all children would inherit the legal status of their mothers. As such, children of enslaved women would be born into slavery. The legal doctrine of partus sequitur ventrem was derived from Roman civil law, specifically the portions concerning slavery and personal property (chattels).

Nat Turner's Rebellion was a rebellion of enslaved Virginians that took place in Southampton County, Virginia, in August 1831, led by Nat Turner. The rebels killed between 55 and 65 people, at least 51 of whom were white. The rebellion was put down within a few days, but Turner survived in hiding for more than two months afterwards. The rebellion was effectively suppressed at Belmont Plantation on the morning of August 23, 1831.

Slavery in New Jersey began in the early 17th century, when Dutch colonists trafficked African slaves for labor to develop their colony of New Netherland. After England took control of the colony in 1664, its colonists continued the importation of slaves from Africa. They also imported "seasoned" slaves from their colonies in the West Indies and enslaved Native Americans from the Carolinas.

The institution of slavery in North America existed from the earliest years of the colonial history of the United States until 1865 when the Thirteenth Amendment permanently abolished slavery throughout the entire United States. It was also abolished among the sovereign Indian tribes in Indian Territory by new peace treaties which the US required after the war.

The Slave Community: Plantation Life in the Antebellum South is a book written by American historian John W. Blassingame. Published in 1972, it is one of the first historical studies of slavery in the United States to be presented from the perspective of the enslaved. The Slave Community contradicted those historians who had interpreted history to suggest that African-American slaves were docile and submissive "Sambos" who enjoyed the benefits of a paternalistic master–slave relationship on southern plantations. Using psychology, Blassingame analyzes fugitive slave narratives published in the 19th century to conclude that an independent culture developed among the enslaved and that there were a variety of personality types exhibited by slaves.

The breeding of enslaved people in the United States was the practice in slave states of the United States of slave owners to systematically force the reproduction of enslaved people to increase their profits. It included coerced sexual relations between enslaved men and women or girls, forced pregnancies of enslaved people, and favoring women or young girls who could produce a relatively large number of children. The objective was to increase the number of slaves without incurring the cost of purchase, and to fill labor shortages caused by the abolition of the Atlantic slave trade.

Slavery in Virginia began with the capture and enslavement of Native Americans during the early days of the English Colony of Virginia and through the late eighteenth century. They primarily worked in tobacco fields. Africans were first brought to colonial Virginia in 1619, when 20 Africans from present-day Angola arrived in Virginia aboard the ship The White Lion.

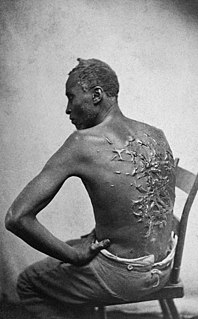

The treatment of enslaved people in the United States varied by time and place, but was generally brutal, especially on plantations. Whipping and rape were routine, but usually not in front of white outsiders, or even the plantation owner's family. An enslaved person could not be a witness against a white; enslaved people were sometimes required to whip other enslaved people, even family members. There were also businesses to which a slave owner could turn over the whipping. Families were often split up by the sale of one or more members, usually never to see or hear of each other again. There were some relatively enlightened slave owners—Nat Turner said his master was kind—but not on large plantations. Only a small minority of enslaved people received anything resembling decent treatment; one contemporary estimate was 10%, not without noting that the ones well treated desired freedom just as much as those poorly treated. Good treatment could vanish upon the death of an owner. As put by William T. Allan, a slaveowner's abolitionist son who could not safely return to Alabama, "cruelty was the rule, and kindness the exception".

Slavery in Cuba was a portion of the larger Atlantic Slave Trade that primarily supported Spanish plantation owners engaged in the sugarcane trade. It was practiced on the island of Cuba from the 16th century until it was abolished by Spanish royal decree on October 7, 1886.

Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers is an American historian. She is an Associate Professor of History at the University of California, Berkeley, and the author of They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South. She is an expert in African-American history, the history of American slavery, and women’s and gender history.

Slavery was legally practiced in the Province of North Carolina and the state of North Carolina until January 1, 1863 when President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. Prior to statehood, there were 41,000 enslaved African-Americans in the Province of North Carolina in 1767. By 1860, the number of slaves in the state of North Carolina was 331,059, about one third of the total population of the state. In 1860, there were nineteen counties in North Carolina where the number of slaves was larger than the free white population. During the antebellum period the state of North Carolina passed several laws to protect the rights of slave owners while disenfranchising the rights of slaves. There was a constant fear amongst white slave owners in North Carolina of slave revolts from the time of the American Revolution. Despite their circumstances, some North Carolina slaves and freed slaves distinguished themselves as artisans, soldiers during the Revolution, religious leaders, and writers.

Marisa J. Fuentes is an American writer, historian, and academic. She is an Associate Professor of Women & Gender Studies and History and the Presidential Term Chair in African American History at Rutgers University, where she has taught since 2009.

References

- ↑ Stacey Messing. "White, Deborah Gray". rutgers.edu. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ "Deborah Gray White". gf.org. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ Deborah Gray White. "TOO HEAVY A LOAD". Kirkus Reviews. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ Gray White, Deborah (February 1999). Ar'n't I a Woman? Female Slaves in the Plantation South (2nd ed.). W.W Norton & Company Inc. pp. 256. ISBN 978-0-393-31481-6 . Retrieved February 3, 2015.