Human rights are moral principles or norms for certain standards of human behaviour and are regularly protected in municipal and international law. They are commonly understood as inalienable, fundamental rights "to which a person is inherently entitled simply because she or he is a human being" and which are "inherent in all human beings", regardless of their age, ethnic origin, location, language, religion, ethnicity, or any other status. They are applicable everywhere and at every time in the sense of being universal, and they are egalitarian in the sense of being the same for everyone. They are regarded as requiring empathy and the rule of law and imposing an obligation on persons to respect the human rights of others, and it is generally considered that they should not be taken away except as a result of due process based on specific circumstances.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is an international document adopted by the United Nations General Assembly that enshrines the rights and freedoms of all human beings. Drafted by a UN committee chaired by Eleanor Roosevelt, it was accepted by the General Assembly as Resolution 217 during its third session on 10 December 1948 at the Palais de Chaillot in Paris, France. Of the 58 members of the United Nations at the time, 48 voted in favour, none against, eight abstained, and two did not vote.

Rights are legal, social, or ethical principles of freedom or entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal system, social convention, or ethical theory. Rights are of essential importance in such disciplines as law and ethics, especially theories of justice and deontology.

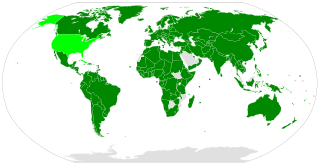

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) is a multilateral treaty that commits nations to respect the civil and political rights of individuals, including the right to life, freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, electoral rights and rights to due process and a fair trial. It was adopted by United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2200A (XXI) on 16 December 1966 and entered into force on 23 March 1976 after its thirty-fifth ratification or accession. As of June 2022, the Covenant has 173 parties and six more signatories without ratification, most notably the People's Republic of China and Cuba; North Korea is the only state that has tried to withdraw.

International human rights law (IHRL) is the body of international law designed to promote human rights on social, regional, and domestic levels. As a form of international law, international human rights law are primarily made up of treaties, agreements between sovereign states intended to have binding legal effect between the parties that have agreed to them; and customary international law. Other international human rights instruments, while not legally binding, contribute to the implementation, understanding and development of international human rights law and have been recognized as a source of political obligation.

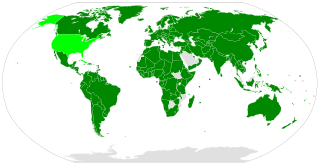

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) is a multilateral treaty adopted by the United Nations General Assembly (GA) on 16 December 1966 through GA. Resolution 2200A (XXI), and came into force on 3 January 1976. It commits its parties to work toward the granting of economic, social, and cultural rights (ESCR) to all individuals including those living in Non-Self-Governing and Trust Territories. The rights include labour rights, the right to health, the right to education, and the right to an adequate standard of living. As of July 2020, the Covenant has 171 parties. A further four countries, including the United States, have signed but not ratified the Covenant.

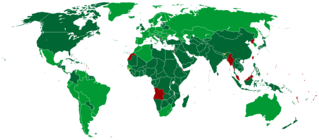

The Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) is an international treaty adopted in 1979 by the United Nations General Assembly. Described as an international bill of rights for women, it was instituted on 3 September 1981 and has been ratified by 189 states. Over fifty countries that have ratified the Convention have done so subject to certain declarations, reservations, and objections, including 38 countries who rejected the enforcement article 29, which addresses means of settlement for disputes concerning the interpretation or application of the convention. Australia's declaration noted the limitations on central government power resulting from its federal constitutional system. The United States and Palau have signed, but not ratified the treaty. The Holy See, Iran, Somalia, Sudan, and Tonga are not signatories to CEDAW.

Economic, social and cultural rights (ESCR) are socio-economic human rights, such as the right to education, right to housing, right to an adequate standard of living, right to health, victims' rights and the right to science and culture. Economic, social and cultural rights are recognised and protected in international and regional human rights instruments. Member states have a legal obligation to respect, protect and fulfil economic, social and cultural rights and are expected to take "progressive action" towards their fulfilment.

The Fundamental Rights, Directive Principles of State Policy and Fundamental Duties' are sections of the Constitution of India that prescribe the fundamental obligations of the states to its citizens and the duties and the rights of the citizens to the State. These sections are considered vital elements of the constitution, which was developed between 1949 by the Constituent Assembly of India.

Minority rights are the normal individual rights as applied to members of racial, ethnic, class, religious, linguistic or gender and sexual minorities, and also the collective rights accorded to any minority group.

The right to food, and its variations, is a human right protecting the right of people to feed themselves in dignity, implying that sufficient food is available, that people have the means to access it, and that it adequately meets the individual's dietary needs. The right to food protects the right of all human beings to be free from hunger, food insecurity, and malnutrition. The right to food implies that governments only have an obligation to hand out enough free food to starving recipients to ensure subsistence, it does not imply a universal right to be fed. Also, if people are deprived of access to food for reasons beyond their control, for example, because they are in detention, in times of war or after natural disasters, the right requires the government to provide food directly.

In law, sex characteristic refers to an attribute defined for the purposes of protecting individuals from discrimination due to their sexual features. The attribute of sex characteristics was first defined in national law in Malta in 2015. The legal term has since been adopted by United Nations, European, and Asia-Pacific institutions, and in a 2017 update to the Yogyakarta Principles on the application of international human rights law in relation to sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression and sex characteristics.

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities is an international human rights treaty of the United Nations intended to protect the rights and dignity of persons with disabilities. Parties to the convention are required to promote, protect, and ensure the full enjoyment of human rights by persons with disabilities and ensure that persons with disabilities enjoy full equality under the law. The Convention serves as a major catalyst in the global disability rights movement enabling a shift from viewing persons with disabilities as objects of charity, medical treatment and social protection towards viewing them as full and equal members of society, with human rights. The convention was the first U.N. human rights treaty of the twenty-first century.

The Declaration on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women is a human rights proclamation issued by the United Nations General Assembly, outlining that body's views on women's rights. It was adopted by the General Assembly on 7 November 1967. The Declaration was an important precursor to the legally binding 1979 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). Its aim was to promote gender equality, specifically for protection of the rights of women. It was drafted by the Commission on the Status of Women in 1967. To implement the principles of the declaration, CEDAW was formed and enforced on 3 December 1981.

The right to housing is the economic, social and cultural rightto adequate housing and shelter. It is recognized in some national constitutions and in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. The right to housing is regarded as a freestanding right in the International human rights law which was clearly in the 1991 General Comment on Adequate Housing by the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. The aspect of the right to housing under ICESCR include: availability of services, infrastructure, material and facilities; legal security of tenure; habitability; accessibility; affordability; location and cultural adequacy.

The Yogyakarta Principles is a document about human rights in the areas of sexual orientation and gender identity that was published as the outcome of an international meeting of human rights groups in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, in November 2006. The principles were supplemented and expanded in 2017 to include new grounds of gender expression and sex characteristics and a number of new principles. However, the Principles have never been accepted by the United Nations (UN) and the attempt to make gender identity and sexual orientation new categories of non-discrimination has been repeatedly rejected by the General Assembly, the UN Human Rights Council and other UN bodies.

The right to sexuality incorporates the right to express one's sexuality and to be free from discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation. Specifically, it relates to the human rights of people of diverse sexual orientations, including lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people, and the protection of those rights, although it is equally applicable to heterosexuality. The right to sexuality and freedom from discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation is based on the universality of human rights and the inalienable nature of rights belonging to every person by virtue of being human.

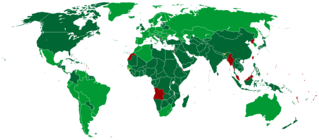

The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) is a United Nations convention. A third-generation human rights instrument, the Convention commits its members to the elimination of racial discrimination and the promotion of understanding among all races. The Convention also requires its parties to criminalize hate speech and criminalize membership in racist organizations.

The gender pay gap in New Zealand is the difference in the median hourly wages of men and women in New Zealand. In 2020 the gender pay gap is 9.5%. It is an economic indicator used to measure pay equality. The gender pay gap is an official statistic published annually by Stats NZ sourced from the Household Labour Force Survey.

The Global Pact for the Environment project was launched in 2017 by a network of experts known as the "International Group of Experts for the Pact" (IGEP). The group is made up of more than a hundred legal experts in environmental law and is chaired by former COP21 President Laurent Fabius.