Deinopidae, also known as net casting spiders, is a family of cribellate spiders first described by Carl Ludwig Koch in 1850. It consists of stick-like elongated spiders that catch prey by stretching a web across their front legs before propelling themselves forward. These unusual webs will stretch two or three times their relaxed size, entangling any prey that touch them. The posterior median eyes have excellent night vision, allowing them to cast nets accurately in low-light conditions. These eyes are larger than the others, and sometimes makes these spiders appear to only have two eyes. Ogre-faced spiders (Deinopis) are the best known genus in this family. The name refers to the perceived physical similarity to the mythological creature of the same name. This family also includes the humped-back spiders (Menneus).

Philodromidae, also known as philodromid crab spiders and running crab spiders, is a family of araneomorph spiders first described by Tord Tamerlan Teodor Thorell in 1870. It contains over 500 species in thirty genera.

Mopiopia is a genus of jumping spiders that was first described by Eugène Louis Simon in 1902.

Castianeira is a genus of ant-like corinnid sac spiders first described by Eugen von Keyserling in 1879. They are found in Eurasia, Africa, and the Americas, but are absent from Australia. Twenty-six species are native to North America, and at least twice as many are native to Mexico and Central America.

Lycosa is a genus of wolf spiders distributed throughout most of the world. Sometimes called the "true tarantula", though not closely related to the spiders most commonly called tarantulas today, Lycosa spp. can be distinguished from common wolf spiders by their relatively large size. This genus includes the European Lycosa tarantula, which was once associated with tarantism, a dubious affliction whose symptoms included shaking, cold sweats, and a high fever, asserted to be curable only by the traditional tarantella dance. No scientific substantiation of that myth is known; the venom of Lycosa spiders is generally not harmful.

Micrathena, known as spiny orbweavers, is a genus of orb-weaver spiders first described by Carl Jakob Sundevall in 1833. Micrathena contains more than a hundred species, most of them Neotropical woodland-dwelling species. The name is derived from the Greek "micro", meaning "small", and the goddess Athena.

Phormictopus is a genus of spiders in the family Theraphosidae (tarantulas) that occurs in the West Indies, mainly Cuba and Hispaniola, with three species probably misplaced in this genus found in Brazil and Argentina.

Ctenus is a genus of wandering spiders first described by Charles Athanase Walckenaer in 1805. It is widely distributed, from South America through Africa to East Asia. Little is known about the toxic potential of the genus Ctenus; however, Ctenus medius has been shown to share some toxic properties with Phoneutria nigriventer, such as proteolytic, hyaluronidase and phospholipase activities, in addition to producing hyperalgesia and edema. The venom of C. medius also interferes with the complement system in concentrations in which the venom of P. nigriventer is inactive, indicating that some species in the genus may have a medically significant venom. The venom of C. medius interferes with the complement component 3 (C3) of the complement system; it affects the central factor of the cascades of the complement, and interferes with the lytic activity of this system, which causes stronger activation and consumption of the complement components. Unlike C. medius, the venom of P. nigriventer does not interfere with lytic activity.

Corinna is a genus of corinnid sac spiders first described by Carl Ludwig Koch in 1841. They are found in Mexico and south to Brazil, and with selected species found in Africa.

Otiothops is a genus of palp-footed spiders that was first described by W. S. MacLeay in 1839.

Odo is a genus of spiders in the family Xenoctenidae, containing 27 species occurring in Central and South America, and Australia.

Wulfila is a genus of ghost spiders first described by O. Pickard-Cambridge in 1895. They are easily recognized by their pale white elongated legs.

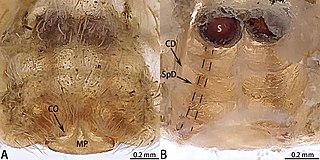

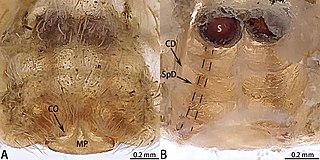

Deinopis spinosa, known generally as the ogrefaced spider or net-casting spider, is a species of ogrefaced spider in the family Deinopidae. It is found in the United States, St. Vincent, and Venezuela. This spider is notable for its use of a net to catch prey. It does this by holding a small web stretched across its legs while it is suspended from a sparse web frame. When prey approaches the spider, it lunges forward and captures the insect in its net. In order to capture prey flying above it the spider uses a backward striking motion. When prey is outside its field of vision this spider appears to use a sensory organ located on its front legs to sense to prey. This sensory organ is known as the metatarsal organ. During the day, the spider is immobile and camouflages itself on its host palm plant. At night, the spider hunts.

Xenoctenidae is a family of araneomorph spiders separated from Miturgidae in 2017.

Asianopis is a genus of Asian net-casting spiders first described by Y. J. Lin, L. Shao and A. Hänggi in 2020.