Formation of Stereotypes

The Mafia

Beginning in the 1880s, Italian immigrants began arriving in the United States, mostly in the Mid-Atlantic region. From 1880 to 1915, almost 15 million Italians would immigrate to the United States, the largest mass migration in modern history. Many immigrants came from the troubled island of Sicily, where crime and disorder were rampant. The large-scale immigration of Italian to North America brought with it elements of the Sicilian Mafia. While these criminal elements were ultimately a minority within the large Italian immigrant community, the influence of yellow journalism tied Italian immigrants with criminality. [2]

Organized crime in the United States is referred to as La Cosa Nostra (Italian for "our thing"). Traditions of organized crime in the United States trace their roots to similar organizations in Sicily and southern Italy during the late 19th century. As Italian Americans normally lived in ethnic neighborhoods, often known as "Little Italy," many traditions and customs from Italy continued over generations. Anti-Italian sentiment was linked to the Mafia, as in the infamous lynchings of 11 Italian Americans in New Orleans on March 14, 1891. Accused of murdering a New Orleans police chief, the suspected Mafia soldiers were assaulted and lynched while in prison awaiting sentencing. The news coverage from the event helped publicize the term "Mafia" in the United States, and from 1891 on, Italian Americans would be associated with the Mafia in the media. [3]

Anarchism

Militant anarchism was considered a significant danger to the United States in the late 19th century and early 20th century. Although the anarchist who assassinated President William McKinley in 1901 was Polish, anarchism was often associated with Italian immigrants and Italian Americans. Italian anarchists were generally immigrants, fueling the anti immigrant feelings of many Americans. Italian American anarchist Luigi Galleani was responsible for multiple assassination attempts on powerful American figures during the Prohibition Era. However, by the 1930s, the association of Italian immigrants with anarchists faded as militant activities became less frequent. [4]

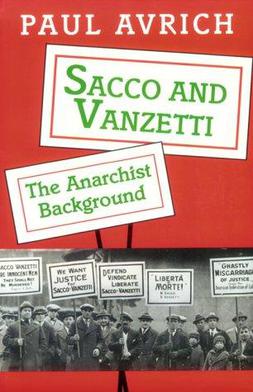

The Sacco and Vanzetti Case

On July 14, 1921, known Italian anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti were tried and convicted for the 1920 murder of two people during an armed robbery. The two Italian immigrants were convicted based on circumstantial evidence, and there were allegations of anti-Italianism among the jury and the presiding judge. Multiple appeals for clemency were denied, and on August 23, 1927 were executed by electric chair, along with the confessed culprit to the crime, Celestino Medeiros. The case of Sacco and Vanzetti is considered an example of anti-Italianism, including prejudice because of their anarchist political beliefs. The press reported extensively on the case, and reports were given of the anti-Italian bias of Judge Thayer. Later newspaper reports were almost entirely silent on the Medeiros confession. [5]

The Sacco and Vanzetti Case is considered a miscarriage of justice, in that the defendants were found guilty over circumstantial evidence, and that the jury held strong biases against the defendants. Many Italian Americans resented the decision and felt that the media unfairly. portrayed them as violent criminals.

Papism and anti-Catholicism

The majority of Italian immigrants to the United States were Catholic, and subject to widespread anti-Catholic discrimination. Nativist movements in the United States in the 1840s opposed Irish immigration mainly on religious grounds, as Nativists were overwhelmingly Protestant. Anti-Catholic movements, notably the Ku-Klux-Klan, opposed Catholics out of fear of papal political control in the United States. Catholics in the United States were often referred to as "Papists," a term which connoted political allegiance to the Pope first, and the United States second. Anti-Catholicism did not factor in the Sacco and Vanzetti Case, as the two defendants were self-professed atheists. [6]