An anapsid is an amniote whose skull lacks one or more skull openings near the temples. Traditionally, the Anapsida are considered the most primitive subclass of amniotes, the ancestral stock from which Synapsida and Diapsida evolved, making anapsids paraphyletic. It is, however, doubtful that all anapsids lack temporal fenestra as a primitive trait, and that all the groups traditionally seen as anapsids truly lacked fenestra.

Synapsida is one of the two major clades of vertebrate animals in the group Amniota, the other being the Sauropsida. The synapsids were the dominant land animals in the late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic, but the only group that survived into the Cenozoic are mammals. Unlike other amniotes, synapsids have a single temporal fenestra, an opening low in the skull roof behind each eye orbit, leaving a bony arch beneath each; this accounts for their name. The distinctive temporal fenestra developed about 318 million years ago during the Late Carboniferous period, when synapsids and sauropsids diverged, but was subsequently merged with the orbit in early mammals.

Amniotes are tetrapod vertebrate animals belonging to the clade Amniota, a large group that comprises the vast majority of living terrestrial and semiaquatic vertebrates. Amniotes evolved from amphibian ancestors during the Carboniferous period and further diverged into two groups, namely the sauropsids and synapsids. They are distinguished from the other living tetrapod clade — the non-amniote lissamphibians — by the development of three extraembryonic membranes, thicker and keratinized skin, and costal respiration.

Sauria is the clade containing the most recent common ancestor of Archosauria and Lepidosauria, and all its descendants. Since most molecular phylogenies recover turtles as more closely related to archosaurs than to lepidosaurs as part of Archelosauria, Sauria can be considered the crown group of diapsids, or reptiles in general. Depending on the systematics, Sauria includes all modern reptiles or most of them as well as various extinct groups.

Sauropsida is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the class Reptilia, though typically used in a broader sense to also include extinct stem-group relatives of modern reptiles and birds. The most popular definition states that Sauropsida is the sibling taxon to Synapsida, the other clade of amniotes which includes mammals as its only modern representatives. Although early synapsids have historically been referred to as "mammal-like reptiles", all synapsids are more closely related to mammals than to any modern reptile. Sauropsids, on the other hand, include all amniotes more closely related to modern reptiles than to mammals. This includes Aves (birds), which are recognized as a subgroup of archosaurian reptiles despite originally being named as a separate class in Linnaean taxonomy.

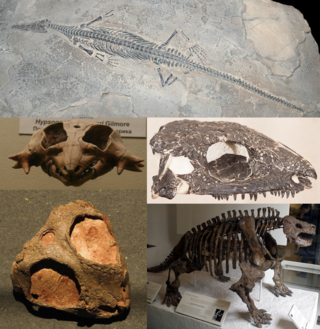

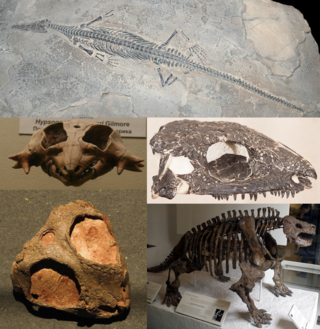

Mesosaurs were a group of small aquatic reptiles that lived during the early Permian period (Cisuralian), roughly 299 to 270 million years ago. Mesosaurs were the first known aquatic reptiles, having apparently returned to an aquatic lifestyle from more terrestrial ancestors. It is uncertain which and how many terrestrial traits these ancestors displayed; recent research cannot establish with confidence if the first amniotes were fully terrestrial, or only amphibious. Most authors consider mesosaurs to have been aquatic, although adult animals may have been amphibious, rather than completely aquatic, as indicated by their moderate skeletal adaptations to a semiaquatic lifestyle. Similarly, their affinities are uncertain; they may have been among the most basal sauropsids or among the most basal parareptiles.

Neodiapsida is a clade, or major branch, of the reptilian family tree, typically defined as including all diapsids apart from some early primitive types known as the araeoscelidians. Modern reptiles and birds belong to the neodiapsid subclade Sauria.

Eureptilia is one of the two major subgroups of the clade Sauropsida, the other one being Parareptilia. Eureptilia includes Diapsida, as well as a number of primitive Permo-Carboniferous forms previously classified under Anapsida, in the old order "Cotylosauria".

Euryapsida is a polyphyletic group of sauropsids that are distinguished by a single temporal fenestra, an opening behind the orbit, under which the post-orbital and squamosal bones articulate. They are different from Synapsida, which also have a single opening behind the orbit, by the placement of the fenestra. In synapsids, this opening is below the articulation of the post-orbital and squamosal bones. It is now commonly believed that euryapsids are in fact diapsids that lost the lower temporal fenestra. Euryapsids are usually considered entirely extinct, although turtles might be part of the sauropterygian clade while other authors disagree. Euryapsida may also be a synonym of Sauropterygia sensu lato.

Eupelycosauria is a large clade of animals characterized by the unique shape of their skull, encompassing all mammals and their closest extinct relatives. They first appeared 308 million years ago during the Early Pennsylvanian epoch, with the fossils of Echinerpeton and perhaps an even earlier genus, Protoclepsydrops, representing just one of the many stages in the evolution of mammals, in contrast to their earlier amniote ancestors.

Varanopidae is an extinct family of amniotes that resembled monitor lizards and may have filled a similar niche, hence the name. Typically, they are considered synapsids that evolved from an Archaeothyris-like synapsid in the Late Carboniferous. Although some studies from the late 2010s have recovered them being taxonomically closer to diapsid reptiles, recent studies from the early 2020s support their traditional placement as synapsids on the basis of high degree of bone labyrinth ossification, maxillary canal morphology and phylogenetic analyses. A varanopid from the latest Middle Permian Pristerognathus Assemblage Zone is the youngest known varanopid and the last member of the "pelycosaur" group of synapsids.

Parareptilia ("near-reptiles") is an extinct subclass or clade of basal sauropsids/reptiles, typically considered the sister taxon to Eureptilia. Parareptiles first arose near the end of the Carboniferous period and achieved their highest diversity during the Permian period. Several ecological innovations were first accomplished by parareptiles among reptiles. These include the first reptiles to return to marine ecosystems (mesosaurs), the first bipedal reptiles, the first reptiles with advanced hearing systems, and the first large herbivorous reptiles. The only parareptiles to survive into the Triassic period were the procolophonoids, a group of small generalists, omnivores, and herbivores. The largest family of procolophonoids, the procolophonids, rediversified in the Triassic, but subsequently declined and became extinct by the end of the period.

Procolophonia is an extinct suborder (clade) of herbivorous reptiles that lived from the Middle Permian till the end of the Triassic period. They were originally included as a suborder of the Cotylosauria but are now considered a clade of Parareptilia. They are closely related to other generally lizard-like Permian reptiles such as the Millerettidae, Bolosauridae, Acleistorhinidae, and Lanthanosuchidae, all of which are included under the Anapsida or "Parareptiles".

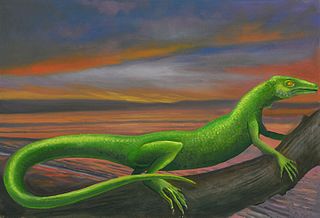

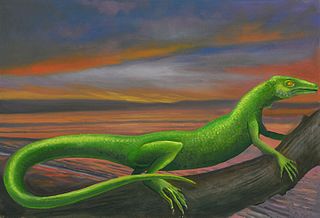

Araeoscelidia or Araeoscelida is a clade of extinct diapsid reptiles superficially resembling lizards, extending from the Late Carboniferous to the Early Permian. The group contains the genera Araeoscelis, Petrolacosaurus, the possibly aquatic Spinoaequalis, and less well-known genera such as Kadaliosaurus and Zarcasaurus. This clade is usually considered to be the sister group to all later diapsids.

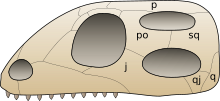

Temporal fenestrae are openings in the temporal region of the skull of some amniotes, behind the orbit. These openings have historically been used to track the evolution and affinities of reptiles. Temporal fenestrae are commonly seen in the fossilized skulls of dinosaurs and other sauropsids. The major reptile group Diapsida, for example, is defined by the presence of two temporal fenestrae on each side of the skull. The infratemporal fenestra, also called the lateral temporal fenestra or lower temporal fenestra, is the lower of the two and is exposed primarily in lateral (side) view.

Eunotosaurus is an extinct genus of amniote, possibly a close relative of turtles. Eunotosaurus lived in the late Middle Permian and fossils can be found in the Karoo Supergroup of South Africa. Eunotosaurus resided in the swamps of what is now southern Africa. Its ribs were wide and flat, forming broad plates similar to a primitive turtle shell, and the vertebrae were nearly identical to those of some turtles. Accordingly, it is often considered as a possible transitional fossil between turtles and their prehistoric ancestors. However, it is possible that these turtle-like features evolved independently of the same features in turtles, since other anatomical studies and phylogenetic analyses suggest that Eunotosaurus may instead have been a parareptile, an early-diverging neodiapsid unrelated to turtles, or a synapsid.

Reptiles arose about 320 million years ago during the Carboniferous period. Reptiles, in the traditional sense of the term, are defined as animals that have scales or scutes, lay land-based hard-shelled eggs, and possess ectothermic metabolisms. So defined, the group is paraphyletic, excluding endothermic animals like birds that are descended from early traditionally-defined reptiles. A definition in accordance with phylogenetic nomenclature, which rejects paraphyletic groups, includes birds while excluding mammals and their synapsid ancestors. So defined, Reptilia is identical to Sauropsida.

Younginidae is an extinct family of diapsid reptiles from the Late Permian and Early Triassic. In a phylogenetic context, younginids are near the base of the clade Neodiapsida. Younginidae includes the species Youngina capensis from the Late Permian of South Africa and Thadeosaurus colcanapi from the Late Permian and Early Triassic of Madagascar. Heleosuchus griesbachi from the Late Permian of South Africa may also be a member of the family.

Pantestudines or Pan-Testudines is the proposed group of all reptiles more closely related to turtles than to any other living animal. It includes both modern turtles and all of their extinct relatives. Pantestudines with a complete shell are placed in the clade Testudinata.

Pappochelys is an extinct genus of diapsid reptile possibly related to turtles. The genus contains only one species, Pappochelys rosinae, from the Middle Triassic of Germany, which was named by paleontologists Rainer Schoch and Hans-Dieter Sues in 2015. The discovery of Pappochelys provides strong support for the placement of turtles within Diapsida, a hypothesis that has long been suggested by molecular data, but never previously by the fossil record. It is morphologically intermediate between the definite stem-turtle Odontochelys from the Late Triassic of China and Eunotosaurus, a reptile from the Middle Permian of South Africa.