Indirect fire is aiming and firing a projectile without relying on a direct line of sight between the gun and its target, as in the case of direct fire. Aiming is performed by calculating azimuth and inclination, and may include correcting aim by observing the fall of shot and calculating new angles.

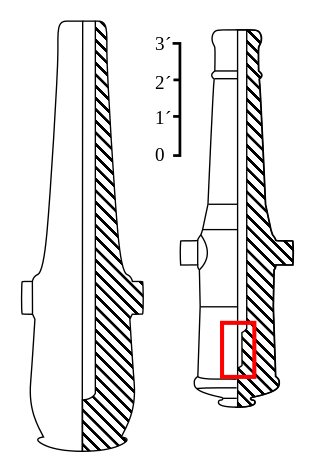

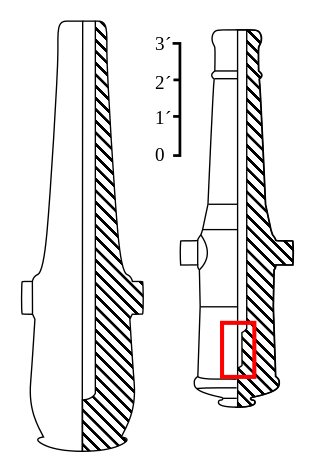

The Roadman gun is any of a series of American Civil War–era columbiads designed by Union artilleryman Thomas Jackson Rodman (1815–1871). The guns were designed to fire both shot and shell. These heavy guns were intended to be mounted in seacoast fortifications. They were built in 8-inch, 10-inch, 13-inch, 15-inch, and 20-inch bore. Other than size, the guns were all nearly identical in design, with a curving bottle shape, large flat cascabels with ratchets or sockets for the elevating mechanism. Roadman guns were true guns that did not have a howitzer-like powder chamber, as did many earlier columbiads. Roadman guns differed from all previous artillery because they were hollow cast, a new technology that Roadman developed that resulted in cast-iron guns that were much stronger than their predecessors.

Fort Monroe is a former military installation in Hampton, Virginia, at Old Point Comfort, the southern tip of the Virginia Peninsula, United States. It is currently managed by partnership between the Fort Monroe Authority for the Commonwealth of Virginia, the National Park Service, and the city of Hampton as the Fort Monroe National Monument. Along with Fort Wool, Fort Monroe originally guarded the navigation channel between the Chesapeake Bay and Hampton Roads—the natural roadstead at the confluence of the Elizabeth, the Nansemond and the James rivers.

A fire-control system (FCS) is a number of components working together, usually a gun data computer, a director and radar, which is designed to assist a ranged weapon system to target, track, and hit a target. It performs the same task as a human gunner firing a weapon, but attempts to do so faster and more accurately.

Coastal artillery is the branch of the armed forces concerned with operating anti-ship artillery or fixed gun batteries in coastal fortifications.

A limber is a two-wheeled cart designed to support the trail of an artillery piece, or the stock of a field carriage such as a caisson or traveling forge, allowing it to be towed. The trail is the hinder end of the stock of a gun-carriage, which rests or slides on the ground when the carriage is unlimbered.

Gun laying is the process of aiming an artillery piece or turret, such as a gun, howitzer, or mortar, on land, in air, or at sea, against surface or aerial targets. It may be laying for direct fire, where the gun is aimed similarly to a rifle, or indirect fire, where firing data is calculated and applied to the sights. The term includes automated aiming using, for example, radar-derived target data and computer-controlled guns.

Montauk Air Force Station was a US military base at Montauk Point on the eastern tip of Long Island, New York. It was decommissioned in 1981 and is now owned by the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation as Camp Hero State Park.

Base end stations were used by the United States Army Coast Artillery Corps as part of fire control systems for locating the positions of attacking ships and controlling the firing of seacoast guns, mortars, or mines to defend against them. A British equivalent was the position finding cell.

A fire control tower is a structure located near the coastline, used to detect and locate enemy vessels offshore, direct fire upon them from coastal batteries, or adjust the aim of guns by spotting shell splashes. Fire control towers came into general use in coastal defence systems in the late 19th century, as rapid development significantly increased the range of both naval guns and coastal artillery. This made fire control more complex. These towers were used in a number of countries' coastal defence systems through 1945, much later in a few cases such as Sweden. The Atlantic Wall in German-occupied Europe during World War II included fire control towers.

A director, also called an auxiliary predictor, is a mechanical or electronic computer that continuously calculates trigonometric firing solutions for use against a moving target, and transmits targeting data to direct the weapon firing crew.

Siege artillery is heavy artillery primarily used in military attacks on fortified positions. At the time of the American Civil War, the U.S. Army classified its artillery into three types, depending on the gun's weight and intended use. Field artillery were light pieces that often traveled with the armies. Siege and garrison artillery were heavy pieces that could be used either in attacking or defending fortified places. Seacoast artillery were the heaviest pieces and were intended to be used in permanent fortifications along the seaboard. They were primarily designed to fire on attacking warships. The distinctions are somewhat arbitrary, as field, siege and garrison, and seacoast artillery were all used in various attacks and defenses of fortifications. This article will focus on the use of heavy artillery in the attack of fortified places during the American Civil War.

East Point Military Reservation was a World War I and World War II coastal defense site located in Nahant, Massachusetts. In 1955–62 it was a Nike missile launch site. In 1967 the site was converted into the Marine Science Center of Northeastern University.

A plotting board was a mechanical device used by the U.S. Army Coast Artillery Corps as part of their fire control system to track the observed course of a target, project its future position, and derive the uncorrected data on azimuth and range needed to direct the fire of the guns of a battery to hit that target. Plotting boards of this sort were first employed by the Coast Artillery around 1905, and were the primary means of calculating firing data until WW2. Towards the end of WW2 these boards were largely replaced by radar and electro-mechanical gun data computers, and were relegated to a back-up role.

In the U.S. Army Coast Artillery Corps, the term fire control system was used to refer to the personnel, facilities, technology and procedures that were used to observe designated targets, estimate their positions, calculate firing data for guns directed to hit those targets, and assess the effectiveness of such fire, making corrections where necessary.

Fort Banks was a U.S. Coast Artillery fort located in Winthrop, Massachusetts. It served to defend Boston Harbor from enemy attack from the sea and was built in the 1809 during what is known as the Endicott period, a time in which the coast defenses of the United States were seriously expanded and upgraded with new technology. Today, the fort's mortar battery is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Fort Heath was a US seacoast military installation for defense of the Boston and Winthrop Harbors with an early 20th-century Coast Artillery fort, a 1930s USCG radio station, prewar naval research facilities, World War II batteries, and a Cold War radar station. The fort was part of the Harbor Defenses of Boston and was garrisoned by the United States Army Coast Artillery Corps. The fort's military structures have been replaced by a residential complex, including the luxurious Forth Heath Apartments, and recreation facilities of Small Park, which has both a commemorative wall and an historical marker for Fort Heath.

The 12-inch coast defense mortar was a weapon of 12-inch (305 mm) caliber emplaced during the 1890s and early 20th century to defend US harbors from seaborne attack. In 1886, when the Endicott Board set forth its initial plan for upgrading the coast defenses of the United States, it relied primarily on mortars, not guns, to defend American harbors. Over the years, provision was made for fortifications that would mount some 476 of these weapons, although not all of these tubes were installed. Ninety-one of these weapons were remounted as railway artillery in 1918-1919, but this was too late to see action in World War I. The railway mortars were only deployed in small quantities, and none overseas. The fixed mortars in the Philippines saw action in the Japanese invasion in World War II. All of the fixed mortars in the United States were scrapped by 1944, as new weapons replaced them, and the railway mortars were scrapped after the war. Today, the only remaining mortars of this type in the 50 states are four at Battery Laidley, part of Fort Desoto near St. Petersburg, Florida, but the remains of coast defense mortar emplacements can be seen at many former Coast Artillery forts across the United States and its former territories. Additional 12-inch mortars and other large-caliber weapons remain in the Philippines.

The Harbor Defenses of Boston was a United States Army Coast Artillery Corps harbor defense command. It coordinated the coast defenses of Boston, Massachusetts from 1895 to 1950, beginning with the Endicott program. These included both coast artillery forts and underwater minefields. The command originated circa 1895 as the Boston Artillery District, was renamed Coast Defenses of Boston in 1913, and again renamed Harbor Defenses of Boston in 1925.

The depression range finder (DRF) was a fire control device used to determine the target's position by observing range and bearing and to calculate firing solutions when gun laying in coastal artillery. It was the main component of a vertical base rangefinding system. It was necessitated by the introduction of rifled artillery from the mid-19th century onwards, which had much greater ranges than the old smoothbore weapons and were consequently more difficult to aim accurately. The DRF was invented by Captain H.S.S. Watkin of the Royal Artillery in the 1870s and was adopted in 1881. It could provide both range and bearing information on a target. The device's inventor also developed a family of similar devices, among them the position finder, which used two telescopes as a horizontal base rangefinding system, around the same time; some of these were called electric position finders. Some position finders retained a depression range finding capability; some of these were called depression position finders. Watkin's family of devices were deployed in position finding cells, a type of fire control tower, often in configurations that allowed both horizontal base and vertical base rangefinding. Watkin's system included automatic electrical updating of range and bearing dials near the guns as the position finders were manipulated, and a system of remotely firing the guns electrically from the position finding cell. The improved system was trialled in 1885 and widely deployed in the 1890s. Functionally equivalent devices were developed for the United States Army Coast Artillery Corps and its predecessors, called depression position finders or azimuth instruments depending on function, adopted in 1896 and deployed widely beginning in the early 1900s as the Endicott program of modern coastal defences was built. These devices were also used by both countries to control submarine (underwater) minefields.