History

Plato quotes Socrates in The Apology as saying that he had a divine or spiritual sign that began when he was a child. It was a voice that turned him away from something he was about to do, although it never encouraged him to do anything. Apuleius later suggested the voice was of a friendly demon [2] and that Socrates deserved this help as he was the most perfect of human beings.

The early Christian philosopher Augustine (354–430) also emphasised the role of divine illumination in our thought, saying that "The mind needs to be enlightened by light from outside itself, so that it can participate in truth, because it is not itself the nature of truth. You will light my lamp, Lord," [3] and "You hear nothing true from me which you have not first told me." [4] According to Augustine, God does not give us certain information, but rather gives us insight into the truth of the information we received for ourselves.

- If we both see that what you say is true, and we both see that what I say is true, then where do we see that? Not I in you, nor you in me, but both of us in that unalterable truth that is above our minds. [5]

Augustine's theory was defended by Christian philosophers of the later Middle Ages, particularly Franciscans such as Bonaventure and Matthew of Aquasparta. According to Bonaventure:

- Things have existence in the mind, in their own nature (proprio genere), and in the eternal art. So the truth of things as they are in the mind or in their own nature – given that both are changeable – is sufficient for the soul to have certain knowledge only if the soul somehow reaches things as they are in the eternal art. [6]

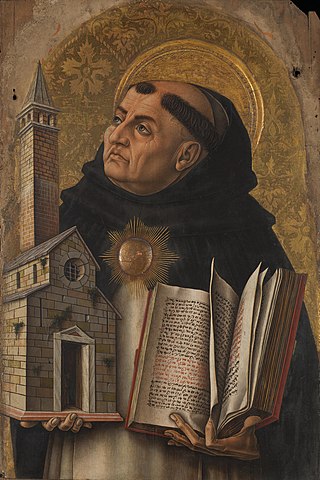

The doctrine was criticised by John Pecham and Roger Marston. Thomas Aquinas is often seen as a harsh critiс of this doctrine; but his position is more nuanced. As Robert Pasnau observes, "Thomas Aquinas is often thought of as the figure most responsible for putting an end to the theory of divine illumination. Although there is some truth to this view, as we will see, it seems more accurate to regard Aquinas as one of the last defenders of the theory, as a proponent of innate Aristotelian illumination." [1] Undoubtedly, Aquinas denied that in this life we have divine ideas as an object of thought, and that divine illumination is sufficient on its own, without the senses, for natural knowledge. He also denied that there is a special continuing divine influence on human thought. People have sufficient capacity for thought on their own, without needing "new illumination added onto their natural illumination." [7] But this natural illumination, which Aquinas distinguishes from the supernatural illumination required for knowledge of intelligible things above human strengths (it is the case of faith and of prophecy), [8] is, nevertheless, divine illumination, according to Aquinas; indeed, he writes that "The material sun sheds its light outside us; but the intelligible Sun, Who is God, shines within us. Hence the natural light bestowed upon the soul is God's enlightenment, whereby we are enlightened to see what pertains to natural knowledge; and for this there is required no further knowledge, but only for such things as surpass natural knowledge." [9] Aquinas asserted also that "the intellectual light that is in us is nothing other than a certain likeness of the uncreated light, obtained through participation, in which the eternal reasons are contained." [10] For this reason, he concluded that, in this life, we know things in the divine ideas as in the principle of knowledge. He also claimed that his position was the right interpretation of Augustine's doctrine on divine illumination; [11] some scholars, as Lydia Schumacher, maintain that his claim is right. [12]

On the other hand, Henry of Ghent defended a different version of the theory, which, according to Henry himself and to various scholars, would be closer to the Augustinian one. Henry argued against Aquinas that Aristotle's theory of abstraction is not enough to explain how we can acquire infallible knowledge of the truth, and must be supplemented by divine illumination. A thing has two exemplars against which it can be compared. The first is a created exemplar which exists in the soul through abstraction. The second is an exemplar which exists outside the soul, and which is uncreated and eternal. But no comparison to a created exemplar can give us infallible truth. Since the dignity of man requires that we can acquire such truth, it follows that we have access to the exemplar in the divine mind. [13]

Henry's defence of divine illumination was strongly criticised by the Franciscan theologian Duns Scotus, who argued that Henry's version of the theory led to scepticism and presented his own version, according to which there are "four senses in which the human intellect sees infallible truths in the divine light. In each sense, the divine light acts not on us but on the objects of our understanding." [1]