The EnglishGreyhound, or simply the Greyhound, is a breed of dog, a sighthound which has been bred for coursing, greyhound racing and hunting. Since the rise in large-scale adoption of retired racing Greyhounds, the breed has seen a resurgence in popularity as a family pet.

A dog breed is a particular type of dog that was purposefully bred by humans to perform specific tasks, such as herding, hunting, and guarding. Dogs are the most variable mammal on Earth, with artificial selection producing upward of 360 globally recognized breeds. These breeds possess distinct traits related to morphology, which include body size, skull shape, tail phenotype, fur type, body shape, and coat colour. However, there is only one species of dog. Their behavioral traits include guarding, herding, and hunting, and personality traits such as hyper-social behavior, boldness, and aggression. Most breeds were derived from small numbers of founders within the last 200 years. As a result of their adaptability to many environments and breedability for human needs, today dogs are the most abundant carnivore species and are dispersed around the world.

The Great Dane is a German breed of large mastiff-sighthound, which descends from hunting dogs of the Middle Ages used to hunt bears, wild boar, and deer. They were also used as guardian dogs of German nobility. It is one of the two largest dog breeds in the world, along with the Irish Wolfhound.

The Boerboel is a South African breed of large dog of mastiff type, used as a family guard dog. It is large, with a short coat, strong bone structure and well-developed muscles.

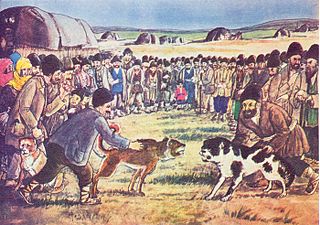

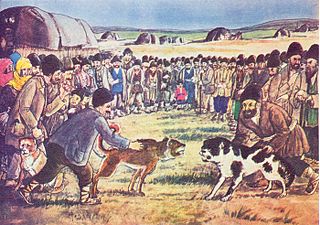

Dog fighting is a type of blood sport that turns game and fighting dogs against each other in a physical fight, often to the death, for the purposes of gambling or entertainment to the spectators. In rural areas, fights are often staged in barns or outdoor pits; in urban areas, fights are often staged in garages, basements, warehouses, alleyways, abandoned buildings, neighborhood playgrounds, or in the streets. Dog fights usually last until one dog is declared a winner, which occurs when one dog fails to scratch, dies, or jumps out of the pit. Sometimes dog fights end without declaring a winner; for instance, the dog's owner may call the fight.

The American bulldog is a large, muscular breed of mastiff-type dog. Their ancestors were brought to the British North American colonies where they worked on small farms and ranches.

A mastiff is a large and powerful type of dog. Mastiffs are among the largest dogs, and typically have a short coat, a long low-set tail and large feet; the skull is large and bulky, the muzzle broad and short (brachycephalic) and the ears drooping and pendant-shaped. European and Asian records dating back 3,000 years show dogs of the mastiff type. Mastiffs have historically been guard dogs, protecting homes and property, although throughout history they have been used as hunting dogs, war dogs and for blood sports, such as fighting each other and other animals, including bulls, bears and even lions.

The Tibetan Mastiff is a large size Tibetan dog breed. Its double coat is medium to long, subject to climate, and found in a wide variety of colors, including solid black, black and tan, various shades of red and bluish-gray, and sometimes with white markings around neck, chest and legs.

The English Mastiff, or simply the Mastiff, is a British dog breed of very large size. It is likely descended from the ancient Alaunt and Pugnaces Britanniae, with a significant input from the Alpine Mastiff in the 19th century. Distinguished by its enormous size, massive head, short coat in a limited range of colours, and always displaying a black mask, the Mastiff is noted for its gentle and loving nature. The lineage of modern dogs can be traced back to the early 19th century, but the modern type was stabilised in the 1880s and refined since. Following a period of sharp decline, the Mastiff has increased its worldwide popularity. Throughout its history the Mastiff has contributed to the development of a number of dog breeds, some generally known as mastiff-type dogs or, confusingly, just as "mastiffs". It is the largest living canine, outweighing the wolf by up to 50 kg (110 lbs) on average.

The Alaunt is an extinct type of dog which came in different forms, with the original possibly having existed in North Caucasus, Central Asia and Europe from ancient times.

The Spanish Mastiff or Mastín Español is a breed of dog from Spain, originally bred to be a guard dog and whose specialized purpose is to be a livestock guardian dog protecting flocks and/or herds from wolves and other predators.

The Dogue de Bordeaux, also known as the Bordeaux Mastiff, French Mastiff or Bordeauxdog, is a large French mastiff breed. A typical brachycephalic mastiff breed, the Bordeaux is a very powerful dog, with a very muscular body.

The Bully Kutta is a type of large dog that originated in the Indian subcontinent, dating back to the 16th century. The Bully Kutta is a working dog used for hunting and guarding. The type is popular in the Punjab region of India and Pakistan, including Haryana and Delhi, as well as in Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu.

The Molossus, also known as the Molossian hound and Epirus mastiff, is an extinct dog breed from Ancient Greece.

Bull and terrier was a common name for crossbreeds between bulldogs and terriers in the early 1800s. Other names included half-and-halfs and half-breds. It was a time in history when, for thousands of years, dogs were classified by use or function, unlike the modern pets of today that were bred to be conformation show dogs and family pets. Bull and terrier crosses were originally bred to function as fighting dogs for bull- and bear-baiting, and other popular blood sports during the Victorian era. The sport of bull baiting required a dog with attributes such as tenacity and courage, a wide frame with heavy bone, and a muscular, protruding jaw. By crossing bulldogs with various terriers from Ireland and Great Britain, breeders introduced "gameness and agility" into the hybrid mix.

Procurator Gynaecii is an official Roman title recorded in the document Notitia Dignitatum, a list of Imperial civil and military officials in the late 4th or early 5th century.

Dog types are broad categories of domestic dogs based on form, function, or style of work, lineage, or appearance. Some may be locally adapted dog types that may have the visual characteristics of a modern purebred dog. In contrast, modern dog breeds strictly adhere to long-established breed standards,[note 1] that began with documented foundation breeding stock sharing a common set of inheritable characteristics, developed by long-established, reputable kennel clubs that recognize the dog as a purebred.

The Alpine mastiff was a type of molosser, or "flock-guardian phenotype" with the same or similar ancestral origins as the Saint Bernard. However, unlike the Saint Bernard, the Alpine mastiff was never a bona fide breed. It is believed to be the progenitor of the modern English Mastiff, as well as other breeds that derive from these types of dogs or that are closely related. M. B. Wynn wrote, "In 1829 a vast light brindle dog of the old Alpine mastiff breed, named L'Ami, was brought from the convent of Great St. Bernard area, and exhibited in London and Liverpool as the largest dog in England." William Cavendish, 5th Duke of Devonshire, is believed to have bred Alpine mastiffs at Chatsworth House. It was earlier thought that ears of the Alpine mastiffs were cut to prevent them becoming frost bitten.

Cultural depictions of dogs in art has become more elaborate as individual breeds evolved and the relationships between human and canine developed. Hunting scenes were popular in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Dogs were depicted to symbolize guidance, protection, loyalty, fidelity, faithfulness, alertness, and love.

Britannia is an annual peer-reviewed academic journal published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies. It was established in 1970 and the first editor-in-chief was Sheppard Frere. The journal covers research on the province of Roman Britain, Iron Age and post-Roman Britain, and western provincial archaeology, as well as excavation reports. It was established because of the large increase in archaeological excavations, increased publication costs, and in order to establish coherence to the field of Roman Britain.