Related Research Articles

Antipsychotics, previously known as neuroleptics and major tranquilizers, are a class of psychotropic medication primarily used to manage psychosis, principally in schizophrenia but also in a range of other psychotic disorders. They are also the mainstay, together with mood stabilizers, in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Moreover, they are also used as adjuncts in the treatment of treatment-resistant major depressive disorder.

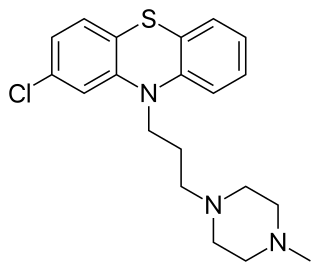

Chlorpromazine (CPZ), marketed under the brand names Thorazine and Largactil among others, is an antipsychotic medication. It is primarily used to treat psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia. Other uses include the treatment of bipolar disorder, severe behavioral problems in children including those with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, nausea and vomiting, anxiety before surgery, and hiccups that do not improve following other measures. It can be given orally, by intramuscular injection, or intravenously.

Haloperidol, sold under the brand name Haldol among others, is a typical antipsychotic medication. Haloperidol is used in the treatment of schizophrenia, tics in Tourette syndrome, mania in bipolar disorder, delirium, agitation, acute psychosis, and hallucinations from alcohol withdrawal. It may be used by mouth or injection into a muscle or a vein. Haloperidol typically works within 30 to 60 minutes. A long-acting formulation may be used as an injection every four weeks by people with schizophrenia or related illnesses, who either forget or refuse to take the medication by mouth.

Fluphenazine, sold under the brand name Prolixin among others, is a high-potency typical antipsychotic medication. It is used in the treatment of chronic psychoses such as schizophrenia, and appears to be about equal in effectiveness to low-potency antipsychotics like chlorpromazine. It is given by mouth, injection into a muscle, or just under the skin. There is also a long acting injectable version that may last for up to four weeks. Fluphenazine decanoate, the depot injection form of fluphenazine, should not be used by people with severe depression.

Typical antipsychotics are a class of antipsychotic drugs first developed in the 1950s and used to treat psychosis. Typical antipsychotics may also be used for the treatment of acute mania, agitation, and other conditions. The first typical antipsychotics to come into medical use were the phenothiazines, namely chlorpromazine which was discovered serendipitously. Another prominent grouping of antipsychotics are the butyrophenones, an example of which is haloperidol. The newer, second-generation antipsychotics, also known as atypical antipsychotics, have largely supplanted the use of typical antipsychotics as first-line agents due to the higher risk of movement disorders in the latter.

The atypical antipsychotics (AAP), also known as second generation antipsychotics (SGAs) and serotonin–dopamine antagonists (SDAs), are a group of antipsychotic drugs largely introduced after the 1970s and used to treat psychiatric conditions. Some atypical antipsychotics have received regulatory approval for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, irritability in autism, and as an adjunct in major depressive disorder.

Quetiapine, sold under the brand name Seroquel among others, is an atypical antipsychotic medication used for the treatment of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. Despite being widely used as a sleep aid due to its sedating effect, the benefits of such use may not outweigh its undesirable side effects. It is taken orally.

Perphenazine is a typical antipsychotic drug. Chemically, it is classified as a piperazinyl phenothiazine. Originally marketed in the United States as Trilafon, it has been in clinical use for decades.

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) is a disorder that results in involuntary repetitive body movements, which may include grimacing, sticking out the tongue or smacking the lips. Additionally, there may be chorea or slow writhing movements. In about 20% of people with TD, the disorder interferes with daily functioning. If TD is present in the setting of a long-term drug therapy, reversibility can be determined primarily by severity of symptoms and how long symptoms have been present before the long-term drug has been stopped.

The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia or the dopamine hypothesis of psychosis is a model that attributes the positive symptoms of schizophrenia to a disturbed and hyperactive dopaminergic signal transduction. The model draws evidence from the observation that a large number of antipsychotics have dopamine-receptor antagonistic effects. The theory, however, does not posit dopamine overabundance as a complete explanation for schizophrenia. Rather, the overactivation of D2 receptors, specifically, is one effect of the global chemical synaptic dysregulation observed in this disorder.

A dopamine antagonist, also known as an anti-dopaminergic and a dopamine receptor antagonist (DRA), is a type of drug which blocks dopamine receptors by receptor antagonism. Most antipsychotics are dopamine antagonists, and as such they have found use in treating schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and stimulant psychosis. Several other dopamine antagonists are antiemetics used in the treatment of nausea and vomiting.

Prochlorperazine, formerly sold under the brand name Compazine among others, is a medication used to treat nausea, migraines, schizophrenia, psychosis and anxiety. It is a less preferred medication for anxiety. It may be taken by mouth, rectally, injection into a vein, or injection into a muscle.

Amisulpride is an antiemetic and antipsychotic medication used at lower doses intravenously to prevent and treat postoperative nausea and vomiting; and at higher doses by mouth to treat schizophrenia and acute psychotic episodes. It is sold under the brand names Barhemsys and Solian, Socian, Deniban and others. At very low doses it is also used to treat dysthymia.

Extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) are symptoms that are archetypically associated with the extrapyramidal system of the brain's cerebral cortex. When such symptoms are caused by medications or other drugs, they are also known as extrapyramidal side effects (EPSE). The symptoms can be acute (short-term) or chronic (long-term). They include movement dysfunction such as dystonia, akathisia, parkinsonism characteristic symptoms such as rigidity, bradykinesia, tremor, and tardive dyskinesia. Extrapyramidal symptoms are a reason why subjects drop out of clinical trials of antipsychotics; of the 213 (14.6%) subjects that dropped out of one of the largest clinical trials of antipsychotics, 58 (27.2%) of those discontinuations were due to EPS.

Asenapine, sold under the brand name Saphris among others, is an atypical antipsychotic medication used to treat schizophrenia and acute mania associated with bipolar disorder as well as the medium to long-term management of bipolar disorder.

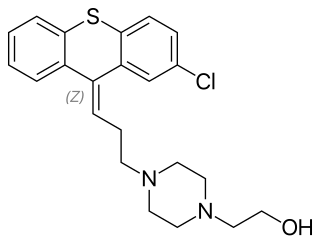

Zuclopenthixol, also known as zuclopentixol, is a medication used to treat schizophrenia and other psychoses. It is classed, pharmacologically, as a typical antipsychotic. Chemically it is a thioxanthene. It is the cis-isomer of clopenthixol. Clopenthixol was introduced in 1961, while zuclopenthixol was introduced in 1978.

Perospirone (Lullan) is an atypical antipsychotic of the azapirone family. It was introduced in Japan by Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma in 2001 for the treatment of schizophrenia and acute cases of bipolar mania.

Tardive psychosis is a term for a hypothetical form of psychosis caused by long-term use of neuroleptics. It was first proposed in 1978 but was questioned by the late 1980s. It was hypothesized that psychosis could arise as neuroleptic medication become decreasingly effective, requiring higher doses, or when not responding to higher doses.

Aripiprazole lauroxil, sold under the brand name Aristada, is a long-acting injectable atypical antipsychotic that was developed by Alkermes. It is an N-acyloxymethyl prodrug of aripiprazole that is administered via intramuscular injection once every four to eight weeks for the treatment of schizophrenia. Aripiprazole lauroxil was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on 5 October 2015.

Antipsychotic switching refers to the process of switching out one antipsychotic for another antipsychotic. There are multiple indications for switching antipsychotics, including inadequate efficacy and drug intolerance. There are several strategies that have been theorized for antipsychotic switching, based upon the timing of discontinuation and tapering of the original antipsychotic and the timing of initiation and titration of the new antipsychotic. Major adverse effects from antipsychotic switching may include supersensitivity syndromes, withdrawal, and rebound syndromes.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Nakata, Y; Kanahara, N; Iyo, M (December 2017). "Dopamine supersensitivity psychosis in schizophrenia: Concepts and implications in clinical practice". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 31 (12): 1511–1518. doi:10.1177/0269881117728428. PMID 28925317. S2CID 1957881.

- 1 2 3 Yin, John; Barr, Alasdair; Ramos-Miguel, Alfredo; Procyshyn, Ric (14 December 2016). "Antipsychotic Induced Dopamine Supersensitivity Psychosis: A Comprehensive Review". Current Neuropharmacology. 15 (1): 174–183. doi:10.2174/1570159X14666160606093602. PMC 5327459 . PMID 27264948.

- 1 2 Seeman, Philip (April 2011). "All Roads to Schizophrenia Lead to Dopamine Supersensitivity and Elevated Dopamine D2High Receptors". CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 17 (2): 118–132. doi:10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00162.x. PMC 6493870 . PMID 20560996.

- 1 2 Brisch, Ralf; Saniotis, Arthur; Wolf, Rainer; Bielau, Hendrik; Bernstein, Hans-Gert; Steiner, Johann; Bogerts, Bernhard; Braun, Anna Katharina; Jankowski, Zbigniew; Kumaritlake, Jaliya; Henneberg, Maciej; Gos, Tomasz (19 May 2014). "The Role of Dopamine in Schizophrenia from a Neurobiological and Evolutionary Perspective: Old Fashioned, but Still in Vogue". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 5: 47. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00047 . PMC 4032934 . PMID 24904434.

- ↑ Katzung, BG; Kruidering-Hall, M; Trevor, AJ (eds.). "Chapter 29: Antipsychotic Agents & Lithium". Katzung & Trevor's Pharmacology: Examination & Board Review (12 ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ Karaş, Hakan; Güdük, Mehmet; Saatcioğlu, Ömer (June 2016). "Withdrawal-Emergent Dyskinesia and Supersensitivity Psychosis Due to Olanzapine Use". Noro Psikiyatri Arsivi. 53 (2): 178–180. doi:10.5152/npa.2015.10122. ISSN 1300-0667. PMC 5353025 . PMID 28360793.

- ↑ Chouinard G, Jones BD, Annable L (1978). "Neuroleptic-induced supersensitivity psychosis". Am J Psychiatry. 135 (11): 1409–10. doi:10.1176/ajp.135.11.1409. PMID 30291.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 4 Palmstierna, T; Wistedt, B (1988). "Tardive psychosis: Does it exist?". Psychopharmacology. 94 (1): 144–5. doi:10.1007/BF00735897. PMID 2894699. S2CID 29048614.

- ↑ Kirkpatrick B, Alphs L, Buchanan RW (1992). "The concept of supersensitivity psychosis". J Nerv Ment Dis. 180 (4): 265–70. doi:10.1097/00005053-199204000-00009. PMID 1348269. S2CID 29597822.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Chouinard G (1991). "Severe cases of neuroleptic-induced supersensitivity psychosis. Diagnostic criteria for the disorder and its treatment". Schizophr Res. 5 (1): 21–33. doi:10.1016/0920-9964(91)90050-2. PMID 1677263. S2CID 38211914.

- ↑ Whitaker, Robert (2015). Anatomy of an epidemic: magic bullets, psychiatric drugs, and the astonishing rise of mental illness in America (1st ed.). Crown Publishers. pp. 105–107. ISBN 9780307452429.

- ↑ Fitzpatrick, Laura (3 May 2010). "Book review: Anatomy of an Epidemic by Robert Whitaker". Time .

- ↑ "Are Psychiatric Medications Making Us Sicker?". Scientific American .

- ↑ Angell, Marcia. "The Epidemic of Mental Illness: Why?". New York Review of Books .

- ↑ Fallon, P; Dursun, S; Deakin, B (February 2012). "Drug-induced supersensitivity psychosis revisited: characteristics of relapse in treatment-compliant patients". Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology. 2 (1): 13–22. doi: 10.1177/2045125311431105 . PMC 3736929 . PMID 23983951.