Chess is a board game for two players, called White and Black, each controlling an army of chess pieces, with the objective to checkmate the opponent's king. It is sometimes called international chess or Western chess to distinguish it from related games such as xiangqi and shogi. The recorded history of chess goes back at least to the emergence of a similar game, chaturanga, in seventh century India. The rules of chess as they are known today emerged in Europe at the end of the 15th century, with standardization and universal acceptance by the end of the 19th century. Today, chess is one of the world's most popular games, and is played by millions of people worldwide.

The rules of chess govern the play of the game of chess. Chess is a two-player abstract strategy board game. Each player controls sixteen pieces of six types on a chessboard. Each type of piece moves in a distinct way. The object of the game is to checkmate the opponent's king; checkmate occurs when a king is threatened with capture and has no escape. A game can end in various ways besides checkmate: a player can resign, and there are several ways a game can end in a draw.

This glossary of chess explains commonly used terms in chess, in alphabetical order. Some of these terms have their own pages, like fork and pin. For a list of unorthodox chess pieces, see Fairy chess piece; for a list of terms specific to chess problems, see Glossary of chess problems; for a list of named opening lines, see List of chess openings; for a list of chess-related games, see List of chess variants; for a list of terms general to board games, see Glossary of board games.

In the game of chess, perpetual check is a situation in which one player can force a draw by an unending series of checks. This typically arises when the player who is checking cannot deliver checkmate, and failing to continue the series of checks gives the opponent at least a chance to win. A draw by perpetual check is no longer one of the rules of chess; however, such a situation will eventually allow a draw claim by either threefold repetition or the fifty-move rule. Players usually agree to a draw long before that, however.

The fifty-move rule in chess states that a player can claim a draw if no capture has been made and no pawn has been moved in the last fifty moves. The purpose of this rule is to prevent a player with no chance of winning from obstinately continuing to play indefinitely or seeking to win by tiring the opponent.

Stalemate is a situation in chess where the player whose turn it is to move is not in check and has no legal move. Stalemate results in a draw. During the endgame, stalemate is a resource that can enable the player with the inferior position to draw the game rather than lose. In more complex positions, stalemate is much rarer, usually taking the form of a swindle that succeeds only if the superior side is inattentive. Stalemate is also a common theme in endgame studies and other chess problems.

Peter Leko is a Hungarian chess player and commentator. He became the world's youngest grandmaster in 1994. He narrowly missed winning the Classical World Chess Championship 2004: the match was drawn 7–7 and so Vladimir Kramnik retained the title. He also came fifth in the FIDE World Chess Championship 2005 and fourth in the World Chess Championship 2007.

Checkmate is any game position in chess and other chess-like games in which a player's king is in check and there is no possible escape. Checkmating the opponent wins the game.

In chess, the threefold repetition rule states that a player may claim a draw if the same position occurs three times during the game. The rule is also known as repetition of position and, in the USCF rules, as triple occurrence of position. Two positions are by definition "the same" if the same types of pieces occupy the same squares, the same player has the move, the remaining castling rights are the same and the possibility to capture en passant is the same. The repeated positions need not occur in succession. The reasoning behind the rule is that if the position occurs three times, no real progress is being made and the game could hypothetically continue indefinitely.

A game of chess can end in a draw by agreement. A player may offer a draw at any stage of a game; if the opponent accepts, the game is a draw. In some competitions, draws by agreement are restricted; for example draw offers may be subject to the discretion of the arbiter, or may be forbidden before move 30 or 40, or even forbidden altogether. The majority of draws in chess are by agreement.

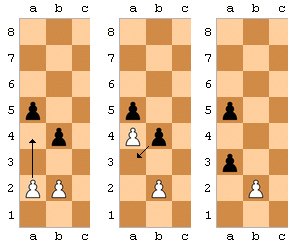

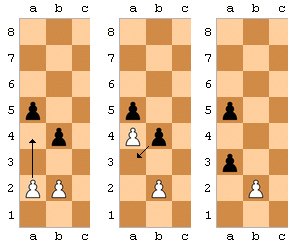

In chess, en passant describes the capture by a pawn of an enemy pawn on the same rank and an adjacent file that has just made an initial two-square advance. The capturing pawn moves to the square that the enemy pawn passed over, as if the enemy pawn had advanced only one square. The rule ensures that a pawn cannot use its two-square move to safely skip past an enemy pawn.

Kriegspiel is a chess variant invented by Henry Michael Temple in 1899 and based upon the original Kriegsspiel developed by Georg von Reiswitz in 1812. In this game, each player can see their own pieces but not those of their opponent. For this reason, it is necessary to have a third person act as an umpire, with full information about the progress of the game. Players attempt to move on their turns, and the umpire declares their attempts 'legal' or 'illegal'. If the move is illegal, the player tries again; if it is legal, that move stands. Each player is given information about checks and captures. They may also ask the umpire if there are any legal captures with a pawn. Since the position of the opponent's pieces is unknown, Kriegspiel is a game of imperfect information.

In chess, promotion is the replacement of a pawn with a new piece when the pawn is moved to its last rank. The player replaces the pawn immediately with a queen, rook, bishop, or knight of the same color. The new piece does not have to be a previously captured piece. Promotion is mandatory when moving to the last rank; the pawn cannot remain as a pawn.

In chess, a blunder is a critically bad move or decision. A blunder severely worsens the player's situation by allowing a loss of material, checkmate, or anything similar. It is usually caused by some tactical oversight, whether due to time trouble, overconfidence, or carelessness. Although blunders are most common in beginner games, all human players make them, even at the world championship level. Creating opportunities for the opponent to blunder is an important skill in over-the-board chess.

The World Chess Championship 2006 was a match between Classical World Chess Champion Vladimir Kramnik and FIDE World Chess Champion Veselin Topalov. The title of World Chess Champion had been split for 13 years. This match, played between September 23 and October 13, 2006, in Elista, Kalmykia, Russia, was to reunite the two World Chess Champion titles and produce an undisputed World Champion.

The Classical World Chess Championship 2004 was held from September 25, 2004, to October 18, 2004, in Brissago, Switzerland. Vladimir Kramnik, the defending champion, played Peter Leko, the challenger, in a fourteen-game match.

Ivan Cheparinov is a Bulgarian chess grandmaster. He is a four-time Bulgarian champion. Cheparinov competed in the FIDE World Cup in 2005, 2007, 2009, 2015 and 2017. He switched his affiliation from Bulgaria to FIDE in 2017, then to Georgia in 2018, and back to Bulgaria in 2020.

In chess, an exchange or trade of chess pieces is a series of closely related moves, typically sequential, in which the two players capture each other's pieces. Any type of pieces except the kings may possibly be exchanged, i.e. captured in an exchange, although a king can capture an opponent's piece. Either the player of the white or the black pieces may make the first capture of the other player's piece in an exchange, followed by the other player capturing a piece of the first player, often referred to as a recapture. Commonly, the word "exchange" is used when the pieces exchanged are of the same type or of about equal value, which is an even exchange. According to chess tactics, a bishop and a knight are usually of about equal value. If the values of the pieces exchanged are not equal, then the player who captures the higher-valued piece can be said to be up the exchange or wins the exchange, while the opponent who captures the lower-valued piece is down the exchange or loses the exchange. Exchanges occur very frequently in chess, in almost every game and usually multiple times per game. Exchanges are often related to the tactics or strategy in a chess game, but often simply occur over the course of a game.

In chess, there is a consensus among players and theorists that the player who makes the first move (White) has an inherent advantage, albeit not one large enough to win under perfect play. This view has been the consensus since at least 1889, when the first World Chess Champion, Wilhelm Steinitz, addressed the issue, although chess has not been solved.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to chess: