The economy of Cuba is a mixed command economy dominated by state-run enterprises. Most of the labor force is employed by the state. In the 1990s, the ruling Communist Party of Cuba encouraged the formation of worker co-operatives and self-employment. In the late 2010s, private property and free-market rights along with foreign direct investment were granted by the 2018 Cuban constitution. Foreign direct investment in various Cuban economic sectors increased before 2018. As of 2000, public-sector employment was 76%, and private-sector employment was 23%, compared to the 1981 ratio of 91% to 8%. Investment is restricted and requires approval by the government. In 2019, Cuba ranked 70th out of 189 countries on the Human Development Index in the high human development category. As of 2012, the country's public debt comprised 35.3% of GDP, inflation (CDP) was 5.5%, and GDP growth was 3%. Housing and transportation costs are low. Cubans receive government-subsidized education, healthcare, and food subsidies.

Transportation in Cuba is the system of railways, roads, airports, waterways, ports and harbours in Cuba:

A currency is a standardization of money in any form, in use or circulation as a medium of exchange, for example banknotes and coins. A more general definition is that a currency is a system of money in common use within a specific environment over time, especially for people in a nation state. Under this definition, the British Pound Sterling (£), euros (€), Japanese yen (¥), and U.S. dollars (US$) are examples of (government-issued) fiat currencies. Currencies may act as stores of value and be traded between nations in foreign exchange markets, which determine the relative values of the different currencies. Currencies in this sense are either chosen by users or decreed by governments, and each type has limited boundaries of acceptance; i.e., legal tender laws may require a particular unit of account for payments to government agencies.

Dollar is the name of more than 20 currencies. The United States dollar, named after the international currency known as the Spanish dollar, was established in 1792 and is the first so named that still survives. Others include the Australian dollar, Brunei dollar, Canadian dollar, Eastern Caribbean dollar, Hong Kong dollar, Jamaican dollar, Liberian dollar, Namibian dollar, New Taiwan dollar, New Zealand dollar, Singapore dollar, Trinidad and Tobago Dollar and several others. The symbol for most of those currencies is the dollar sign $ in the same way as many countries using peso currencies. The name "dollar" originates from Bohemia and a 29 g silver-coin called the Joachimsthaler.

The peso is the currency of Argentina, identified by the symbol $ preceding the amount in the same way as many countries using peso or dollar currencies. It is subdivided into 100 centavos. Its ISO 4217 code is ARS.

In public finance, a currency board is a monetary authority which is required to maintain a fixed exchange rate with a foreign currency. This policy objective requires the conventional objectives of a central bank to be subordinated to the exchange rate target. In colonial administration, currency boards were popular because of the advantages of printing appropriate denominations for local conditions, and it also benefited the colony with the seigniorage revenue. However, after World War II many independent countries preferred to have central banks and independent currencies.

In macroeconomics and modern monetary policy, a devaluation is an official lowering of the value of a country's currency within a fixed exchange-rate system, in which a monetary authority formally sets a lower exchange rate of the national currency in relation to a foreign reference currency or currency basket. The opposite of devaluation, a change in the exchange rate making the domestic currency more expensive, is called a revaluation. A monetary authority maintains a fixed value of its currency by being ready to buy or sell foreign currency with the domestic currency at a stated rate; a devaluation is an indication that the monetary authority will buy and sell foreign currency at a lower rate.

The Argentine Great Depression was an economic depression in Argentina, which began in the third quarter of 1998 and lasted until the second quarter of 2002. It followed the fifteen years stagnation and a brief period of free-market reforms.

The Cuban peso also known as moneda nacional, is the official currency of Cuba.

The convertible peso was one of two official currencies in Cuba, the other being the Cuban peso. It had been in limited use since 1994, when its value was pegged 1:1 to the United States dollar. The convertible peso functioned as foreign exchange certificates.

Convertibility is the quality that allows money or other financial instruments to be converted into other liquid stores of value. Convertibility is an important factor in international trade, where instruments valued in different currencies must be exchanged.

The Convertibility plan was a plan by the Argentine Currency Board that pegged the Argentine peso to the U.S. dollar between 1991 and 2002 in an attempt to eliminate hyperinflation and stimulate economic growth. While it initially met with considerable success, the board's actions ultimately failed. The peso was only pegged to the dollar until 2002.

The Patacón was a bond issued by the government of the province of Buenos Aires, Argentina, during 2001. The patacones were used to pay government bills, including state employees' salaries during a period when the economic crisis caused regular currency to be scarce. Patacones then circulated in the economy in much the same way as pesos.

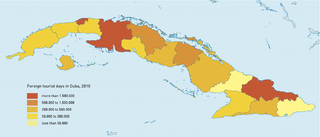

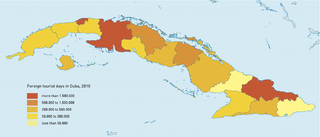

Tourism in Cuba is an industry that generates over 4.7 million arrivals as of 2018, and is one of the main sources of revenue for the island. With its favorable climate, beaches, colonial architecture and distinct cultural history, Cuba has long been an attractive destination for tourists. "Cuba treasures 253 protected areas, 257 national monuments, 7 UNESCO World Heritage Sites, 7 Natural Biosphere Reserves and 13 Fauna Refuge among other non-tourist zones."

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbean Sea, Gulf of Mexico, and Atlantic Ocean meet. Cuba is located east of the Yucatán Peninsula (Mexico), south of both the American state of Florida and the Bahamas, west of Hispaniola, and north of both Jamaica and the Cayman Islands. Havana is the largest city and capital; other major cities include Santiago de Cuba and Camagüey. The official area of the Republic of Cuba is 109,884 km2 (42,426 sq mi) but a total of 350,730 km2 (135,420 sq mi) including the exclusive economic zone. Cuba is the second-most populous country in the Caribbean after Haiti, with over 11 million inhabitants.

Prostitution in Cuba is not officially illegal; however, there is legislation against pimps, sexual exploitation of minors, and pornography. Sex tourism has existed in the country, both before and after the 1959 Cuban Revolution. Many Cubans do not consider the practice immoral. In Cuban slang, female prostitutes are called Jineteras, and gay male prostitutes are called Jineteros or Pingueros. The terms literally mean "jockey" or "rider", and colloquially "sexual jockey", and connotes sexual control during intercourse. The terms also have the broader meaning of "hustler", and are related to jineterismo, a range of illegal or semi-legal economic activities related to tourism in Cuba. Stereotypically a jinetera is represented as a working-class Afro-Cuban woman. Black and mixed-race prostitutes are generally preferred by foreign tourists seeking to buy sex on the island. UNAIDS estimate there are 89,000 prostitutes in the country.

The internet in Cuba covers telecommunications in Cuba including the Cuban grassroots wireless community network and Internet censorship in Cuba.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Cuba:

The dollarization of Cuba refer to macroeconomic policies implemented with the aim at stabilising the Cuban economy after 1993. They were initially enacted to offset the economic imbalances which was a result of the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. The main aspect of these reforms was to legalize the then illegal U.S. Dollar and regulate its usage in the island's economy.