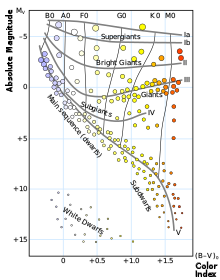

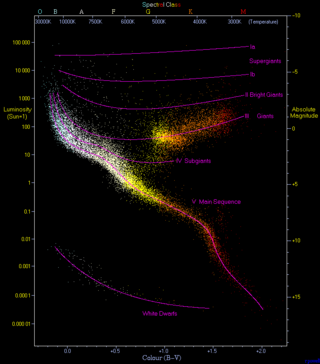

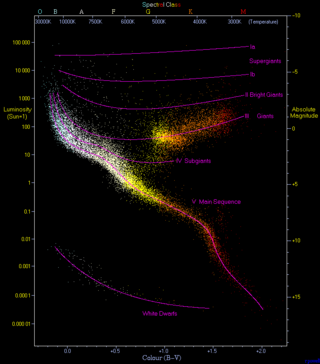

In astronomy, the main sequence is a classification of stars which appear on plots of stellar color versus brightness as a continuous and distinctive band. Stars on this band are known as main-sequence stars or dwarf stars, and positions of stars on and off the band are believed to indicate their physical properties, as well as their progress through several types of star life-cycles. These are the most numerous true stars in the universe and include the Sun. Color-magnitude plots are known as Hertzsprung–Russell diagrams after Ejnar Hertzsprung and Henry Norris Russell.

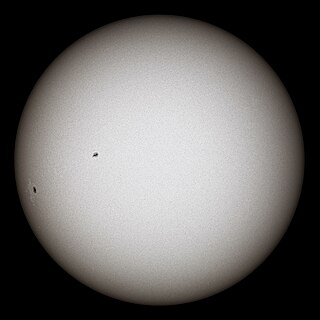

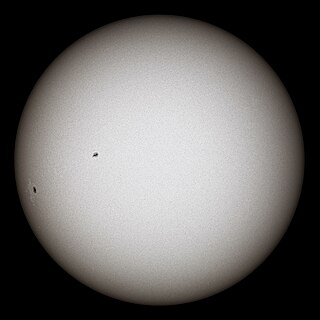

A star is a luminous spheroid of plasma held together by self-gravity. The nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked eye at night; their immense distances from Earth make them appear as fixed points of light. The most prominent stars have been categorised into constellations and asterisms, and many of the brightest stars have proper names. Astronomers have assembled star catalogues that identify the known stars and provide standardized stellar designations. The observable universe contains an estimated 1022 to 1024 stars. Only about 4,000 of these stars are visible to the naked eye—all within the Milky Way galaxy.

Stellar evolution is the process by which a star changes over the course of time. Depending on the mass of the star, its lifetime can range from a few million years for the most massive to trillions of years for the least massive, which is considerably longer than the current age of the universe. The table shows the lifetimes of stars as a function of their masses. All stars are formed from collapsing clouds of gas and dust, often called nebulae or molecular clouds. Over the course of millions of years, these protostars settle down into a state of equilibrium, becoming what is known as a main-sequence star.

In astronomy, stellar classification is the classification of stars based on their spectral characteristics. Electromagnetic radiation from the star is analyzed by splitting it with a prism or diffraction grating into a spectrum exhibiting the rainbow of colors interspersed with spectral lines. Each line indicates a particular chemical element or molecule, with the line strength indicating the abundance of that element. The strengths of the different spectral lines vary mainly due to the temperature of the photosphere, although in some cases there are true abundance differences. The spectral class of a star is a short code primarily summarizing the ionization state, giving an objective measure of the photosphere's temperature.

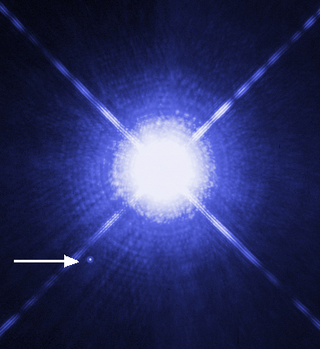

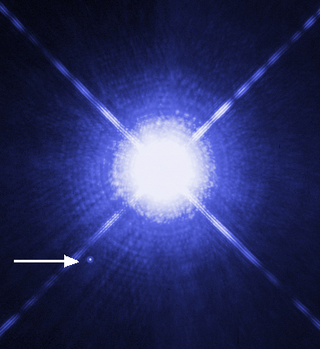

A white dwarf is a stellar core remnant composed mostly of electron-degenerate matter. A white dwarf is very dense: its mass is comparable to the Sun's, while its volume is comparable to Earth's. A white dwarf's low luminosity comes from the emission of residual thermal energy; no fusion takes place in a white dwarf. The nearest known white dwarf is Sirius B, at 8.6 light years, the smaller component of the Sirius binary star. There are currently thought to be eight white dwarfs among the hundred star systems nearest the Sun. The unusual faintness of white dwarfs was first recognized in 1910. The name white dwarf was coined by Willem Luyten in 1922.

A red dwarf is the smallest kind of star on the main sequence. Red dwarfs are by far the most common type of star in the Milky Way, at least in the neighborhood of the Sun. However, due to their low luminosity, individual red dwarfs cannot be easily observed. From Earth, not one star that fits the stricter definitions of a red dwarf is visible to the naked eye. Proxima Centauri, the star nearest to the Sun, is a red dwarf, as are fifty of the sixty nearest stars. According to some estimates, red dwarfs make up three-quarters of the stars in the Milky Way.

Supergiants are among the most massive and most luminous stars. Supergiant stars occupy the top region of the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram with absolute visual magnitudes between about −3 and −8. The temperature range of supergiant stars spans from about 3,400 K to over 20,000 K.

Red supergiants (RSGs) are stars with a supergiant luminosity class of spectral type K or M. They are the largest stars in the universe in terms of volume, although they are not the most massive or luminous. Betelgeuse and Antares A are the brightest and best known red supergiants (RSGs), indeed the only first magnitude red supergiant stars.

In astronomy, a blue giant is a hot star with a luminosity class of III (giant) or II. In the standard Hertzsprung–Russell diagram, these stars lie above and to the right of the main sequence.

A blue supergiant (BSG) is a hot, luminous star, often referred to as an OB supergiant. They have luminosity class I and spectral class B9 or earlier.

A giant star, also simply a giant, is a star with substantially larger radius and luminosity than a main-sequence star of the same surface temperature. They lie above the main sequence on the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram and correspond to luminosity classes II and III. The terms giant and dwarf were coined for stars of quite different luminosity despite similar temperature or spectral type by Ejnar Hertzsprung about 1905.

The red-giant branch (RGB), sometimes called the first giant branch, is the portion of the giant branch before helium ignition occurs in the course of stellar evolution. It is a stage that follows the main sequence for low- to intermediate-mass stars. Red-giant-branch stars have an inert helium core surrounded by a shell of hydrogen fusing via the CNO cycle. They are K- and M-class stars much larger and more luminous than main-sequence stars of the same temperature.

A subgiant is a star that is brighter than a normal main-sequence star of the same spectral class, but not as bright as giant stars. The term subgiant is applied both to a particular spectral luminosity class and to a stage in the evolution of a star.

A blue dwarf is a predicted class of star that develops from a red dwarf after it has exhausted much of its hydrogen fuel supply. Because red dwarfs fuse their hydrogen slowly and are fully convective, they are predicted to have lifespans of trillions of years; the Universe is currently not old enough for any blue dwarfs to have formed yet. Their future existence is predicted based on theoretical models.

An O-type main-sequence star is a main-sequence star of spectral type O and luminosity class V. These stars have between 15 and 90 times the mass of the Sun and surface temperatures between 30,000 and 50,000 K. They are between 40,000 and 1,000,000 times as luminous as the Sun.

A yellow supergiant (YSG) is a star, generally of spectral type F or G, having a supergiant luminosity class. They are stars that have evolved away from the main sequence, expanding and becoming more luminous.

A red giant is a luminous giant star of low or intermediate mass in a late phase of stellar evolution. The outer atmosphere is inflated and tenuous, making the radius large and the surface temperature around 5,000 K or lower. The appearance of the red giant is from yellow-white to reddish-orange, including the spectral types K and M, sometimes G, but also class S stars and most carbon stars.

A stellar core is the extremely hot, dense region at the center of a star. For an ordinary main sequence star, the core region is the volume where the temperature and pressure conditions allow for energy production through thermonuclear fusion of hydrogen into helium. This energy in turn counterbalances the mass of the star pressing inward; a process that self-maintains the conditions in thermal and hydrostatic equilibrium. The minimum temperature required for stellar hydrogen fusion exceeds 107 K (10 MK), while the density at the core of the Sun is over 100 g/cm3. The core is surrounded by the stellar envelope, which transports energy from the core to the stellar atmosphere where it is radiated away into space.

An O-type star is a hot, blue-white star of spectral type O in the Yerkes classification system employed by astronomers. They have temperatures in excess of 30,000 kelvins (K). Stars of this type have strong absorption lines of ionised helium, strong lines of other ionised elements, and hydrogen and neutral helium lines weaker than spectral type B.

In the field of stellar evolution, a blue loop is a stage in the life of an evolved star where it changes from a cool star to a hotter one before cooling again. The name derives from the shape of the evolutionary track on a Hertzsprung–Russell diagram which forms a loop towards the blue side of the diagram.