A guild is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular territory. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradespeople belonging to a professional association. They sometimes depended on grants of letters patent from a monarch or other ruler to enforce the flow of trade to their self-employed members, and to retain ownership of tools and the supply of materials, but most were regulated by the city government. Guild members found guilty of cheating the public would be fined or banned from the guild. A lasting legacy of traditional guilds are the guildhalls constructed and used as guild meeting-places.

A merchant is a person who trades in commodities produced by other people, especially one who trades with foreign countries. Historically, a merchant is anyone who is involved in business or trade. Merchants have operated for as long as industry, commerce, and trade have existed. In 16th-century Europe, two different terms for merchants emerged: meerseniers referred to local traders and koopman referred to merchants who operated on a global stage, importing and exporting goods over vast distances and offering added-value services such as credit and finance.

A market town is a settlement most common in Europe that obtained by custom or royal charter, in the Middle Ages, a market right, which allowed it to host a regular market; this distinguished it from a village or city. In Britain, small rural towns with a hinterland of villages are still commonly called market towns, as sometimes reflected in their names.

England in the Middle Ages concerns the history of England during the medieval period, from the end of the 5th century through to the start of the Early Modern period in 1485. When England emerged from the collapse of the Roman Empire, the economy was in tatters and many of the towns abandoned. After several centuries of Germanic immigration, new identities and cultures began to emerge, developing into kingdoms that competed for power. A rich artistic culture flourished under the Anglo-Saxons, producing epic poems such as Beowulf and sophisticated metalwork. The Anglo-Saxons converted to Christianity in the 7th century and a network of monasteries and convents were built across England. In the 8th and 9th centuries England faced fierce Viking attacks, and the fighting lasted for many decades, eventually establishing Wessex as the most powerful kingdom and promoting the growth of an English identity. Despite repeated crises of succession and a Danish seizure of power at the start of the 11th century, it can also be argued that by the 1060s England was a powerful, centralised state with a strong military and successful economy.

It is believed that the first Jews in England arrived during the Norman Conquest of the country by William the Conqueror in 1066. The first written record of Jewish settlement in England dates from 1070. They suffered massacres in 1189–90. In 1290, all Jews were expelled from England by the Edict of Expulsion.

Sir Michael Moissey Postan FBA was a British historian. He was known informally as Munia Postan.

Mercery (from French mercerie, meaning "habderdashery" or "haberdashery" initially referred to silk, linen and fustian textiles among various other piece goods imported to England in the 12th century. Eventually, the term evolved to refer to a merchant or trader of textile goods, especially imported textile goods, particularly in England. A merchant would be known as a mercer, and the profession as mercery.

The Treaty of Utrecht was signed in 1474 after the Anglo-Hanseatic War between England and the Hanseatic League.

England in the High Middle Ages includes the history of England between the Norman Conquest in 1066 and the death of King John, considered by some to be the last of the Angevin kings of England, in 1216. A disputed succession and victory at the Battle of Hastings led to the conquest of England by William of Normandy in 1066. This linked the crown of England with possessions in France and brought a new aristocracy to the country that dominated landholding, government and the church. They brought with them the French language and maintained their rule through a system of castles and the introduction of a feudal system of landholding. By the time of William's death in 1087, England formed the largest part of an Anglo-Norman empire, ruled by nobles with landholdings across England, Normandy and Wales. William's sons disputed succession to his lands, with William II emerging as ruler of England and much of Normandy. On his death in 1100 his younger brother claimed the throne as Henry I and defeated his brother Robert to reunite England and Normandy. Henry was a ruthless yet effective king, but after the death of his only male heir William Adelin in the White Ship tragedy, he persuaded his barons to recognise his daughter Matilda as heir. When Henry died in 1135 her cousin Stephen of Blois had himself proclaimed king, leading to a civil war known as The Anarchy. Eventually Stephen recognised Matilda's son Henry as his heir and when Stephen died in 1154, he succeeded as Henry II.

The history of England during the Late Middle Ages covers from the thirteenth century, the end of the Angevins, and the accession of Henry III – considered by many to mark the start of the Plantagenet dynasty – until the accession to the throne of the Tudor dynasty in 1485, which is often taken as the most convenient marker for the end of the Middle Ages and the start of the English Renaissance and early modern Britain.

The Champagne fairs were an annual cycle of trade fairs which flourished in different towns of the County of Champagne in Northeastern France in the 12th and 13th centuries, originating in local agricultural and stock fairs. Each fair lasted about 2 to 3 weeks. The Champagne fairs, sited on ancient land routes and largely self-regulated through the development of the Lex mercatoria, became an important engine in the reviving economic history of medieval Europe, "veritable nerve centers" serving as a premier market for textiles, leather, fur, and spices. At their height, in the late 12th and the 13th century, the fairs linked the cloth-producing cities of the Low Countries with the Italian dyeing and exporting centers, with Genoa in the lead, dominating the commercial and banking relations operating at the frontier region between the north and the Mediterranean. The Champagne fairs were one of the earliest manifestations of a linked European economy, a characteristic of the High Middle Ages.

This article covers the Economic history of Europe from about 1000 AD to the present. For the context, see History of Europe.

A charter fair in England is a street fair or market which was established by Royal Charter. Many charter fairs date back to the Middle Ages, with their heyday occurring during the 13th century. Originally, most charter fairs started as street markets but since the 19th century the trading aspect has been superseded by entertainment; many charter fairs are now the venue for travelling funfairs run by showmen.

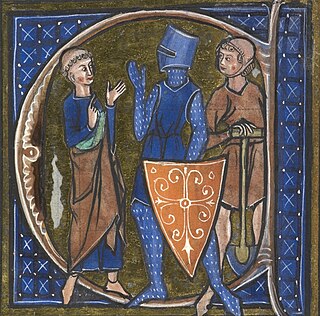

The medieval English saw their economy as comprising three groups – the clergy, who prayed; the knights, who fought; and the peasants, who worked the landtowns involved in international trade. Over the five centuries of the Middle Ages, the English economy would at first grow and then suffer an acute crisis, resulting in significant political and economic change. Despite economic dislocation in urban and extraction economies, including shifts in the holders of wealth and the location of these economies, the economic output of towns and mines developed and intensified over the period. By the end of the period, England had a weak government, by later standards, overseeing an economy dominated by rented farms controlled by gentry, and a thriving community of indigenous English merchants and corporations.

The economics of English agriculture in the Middle Ages is the economic history of English agriculture from the Norman invasion in 1066, to the death of Henry VII in 1509. England's economy was fundamentally agricultural throughout the period, though even before the invasion the market economy was important to producers. Norman institutions, including serfdom, were superimposed on an existing system of open fields.

The Economics of English Mining in the Middle Ages is the economic history of English mining from the Norman invasion in 1066, to the death of Henry VII in 1509. England's economy was fundamentally agricultural throughout the period, but the mining of iron, tin, lead and silver, and later coal, played an important part within the English medieval economy.

The Great Slump was an economic depression that occurred in England from the 1430s to the 1480s.

The medieval English wool trade was one of the most important factors in the medieval English economy. The medievalist John Munro notes that "[n]o form of manufacturing had a greater impact upon the economy and society of medieval Britain than did those industries producing cloths from various kinds of wool." The trade's liveliest period, 1250–1350, was 'an era when trade in wool had been the backbone and driving force in the English medieval economy'.

The Shrewsbury Drapers Company was a trade organisation founded in 1462 in the town of Shrewsbury, Shropshire, England. The members were wholesale dealers in wool and later woollen cloth. The Company dominated the trade in Welsh cloth and in 1566 was given a regional monopoly in the Welsh Wool trade. In the seventeenth century the trade had difficulties particularly during the English Civil war and then further declined in the eighteenth century with the industrialisation of cloth production and the improvement of transport infrastructure. This made it practical for merchants from Liverpool and elsewhere to travel into Wales and purchase cloth directly from the producers. The Reform Acts of the early nineteenth century took away the power of the trade guilds and the trade ceased. Since that time the Shrewsbury Drapers Company has survived and continues as a charity that runs almshouses in Shrewsbury.

The textile industry in Aachen has a history that dates back to the Middle Ages. The Imperial city of Aachen was the main woolen center of the Rhineland. Certain kind of woolens made there were illustrated as "Aachen fine cloth". These high-quality fine woolens have a plain weave structure using carded merino wool yarns, and a raised surface. The production of high-quality, fine cloth required fine foreign wool and skilled craftsmen and was reserved for town craftsmen. It involved regulated steps including sorting, combing, washing, spinning, fulling, dyeing, shearing, and pressing the wool. The finished products were inspected and authorized with a town trademark before being sold and exported. Fine cloth was a major export in the Middle Ages.