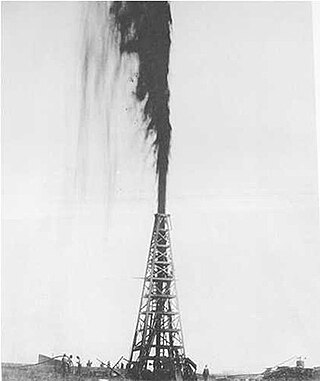

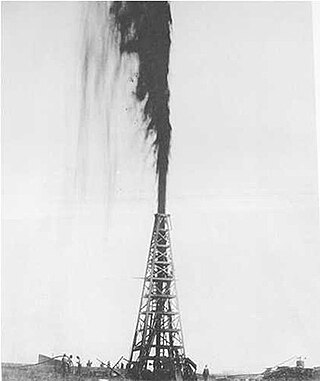

Ixtoc 1 was an exploratory oil well being drilled by the semi-submersible drilling rig Sedco 135 in the Bay of Campeche of the Gulf of Mexico, about 100 km (62 mi) northwest of Ciudad del Carmen, Campeche in waters 50 m (164 ft) deep. On 3 June 1979, the well suffered a blowout resulting in the largest oil spill in history at its time. To-date, it remains the second largest oil spill in history after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

Matthew Roy Simmons was founder and chairman emeritus of Simmons & Company International, and was a prominent figure in the field of peak oil. Simmons was motivated by the 1973 energy crisis to create an investment banking firm catering to oil companies. He served as an energy adviser to U.S. President George W. Bush and was a member of the National Petroleum Council and the Council on Foreign Relations.

A blowout is the uncontrolled release of crude oil and/or natural gas from an oil well or gas well after pressure control systems have failed. Modern wells have blowout preventers intended to prevent such an occurrence. An accidental spark during a blowout can lead to a catastrophic oil or gas fire.

A blowout preventer (BOP) is a specialized valve or similar mechanical device, used to seal, control and monitor oil and gas wells to prevent blowouts, the uncontrolled release of crude oil or natural gas from a well. They are usually installed in stacks of other valves.

Deepwater Horizon was an ultra-deepwater, dynamically positioned, semi-submersible offshore drilling rig owned by Transocean and operated by BP. On 20 April 2010, while drilling at the Macondo Prospect, a blowout caused an explosion on the rig that killed 11 crewmen and ignited a fireball visible from 40 miles (64 km) away. The fire was inextinguishable and, two days later, on 22 April, the Horizon sank, leaving the well gushing at the seabed and turning into the largest marine oil spill in history.

Q4000 is a multi-purpose oil field construction and intervention vessel ordered in 1999 by Cal Dive International, and was built at the Keppel AmFELS shipyard in Brownsville, Texas for $180 million. She was delivered in 2002 and operates under the flag of the United States. She is operated by Helix Energy Solutions Group. The original Q4000 concept was conceived and is owned by SPD/McClure. The design was later modified by Bennett Offshore, which was selected to develop both the basic and detailed design.

The Deepwater Horizon oil spill was an environmental disaster which began on 20 April 2010, off the coast of the United States in the Gulf of Mexico on the BP-operated Macondo Prospect, considered the largest marine oil spill in the history of the petroleum industry and estimated to be 8 to 31 percent larger in volume than the previous largest, the Ixtoc I oil spill, also in the Gulf of Mexico. Caused in the aftermath of a blowout and explosion on the Deepwater Horizon oil platform, the United States federal government estimated the total discharge at 4.9 MMbbl. After several failed efforts to contain the flow, the well was declared sealed on 19 September 2010. Reports in early 2012 indicated that the well site was still leaking. The Deepwater Horizon oil spill is regarded as one of the largest environmental disasters in world history.

The Macondo Prospect is an oil and gas prospect in the United States Exclusive Economic Zone of the Gulf of Mexico, off the coast of Louisiana. The prospect was the site of the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig explosion in April 2010 that led to a major oil spill in the region from the first exploration well, named itself MC252-1, which had been designed to investigate the existence of the prospect.

On April 20, 2010, an explosion and fire occurred on the Deepwater Horizon semi-submersible mobile offshore drilling unit, which was owned and operated by Transocean and drilling for BP in the Macondo Prospect oil field about 40 miles (64 km) southeast off the Louisiana coast. The explosion and subsequent fire resulted in the sinking of the Deepwater Horizon and the deaths of 11 workers; 17 others were injured. The same blowout that caused the explosion also caused an oil well fire and a massive offshore oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, considered the largest accidental marine oil spill in the world, and the largest environmental disaster in United States history.

The following is a timeline of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. It was a massive oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, the largest offshore spill in U.S. history. It was a result of the well blowout that began with the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig explosion on April 20, 2010.

Discoverer Enterprise is a fifth generation deepwater double hulled dynamically positioned drillship owned and operated by Transocean Offshore Deepwater Drilling Inc., capable of operating in moderate environments and water depths up to 3,049 m (10,000 ft) using an 18.75 in (47.6 cm), 15,000 psi blowout preventer (BOP), and a 21 in (53 cm) outside diameter (OD) marine riser. From 1998 to 2005 the vessel was Panama-flagged and currently flies the flag of convenience of the Marshall Islands.

This article covers the effect of the Deepwater Horizon disaster and the resulting oil spill on global and national economies and the energy industry.

Following is a timeline of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill for June 2010.

Following is a timeline of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill for July 2010.

Following is a Timeline of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill for May 2010.

Following is a timeline of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill for August 2010.

The Deepwater Horizon investigation included several investigations and commissions, among others reports by National Incident Commander Thad Allen, United States Coast Guard, National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and Offshore Drilling, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation and Enforcement, National Academy of Engineering, National Research Council, Government Accountability Office, National Oil Spill Commission, and Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board.

The Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill Trust is the $20 billion trust fund established by BP to settle claims arising from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. The fund was established to be used for natural resource damages, state and local response costs and individual compensation. It was established as Gulf Coast Claims Facility (GCCF), announced on 16 June 2010 after a meeting of BP executives with U.S. President Barack Obama. In June 2012, the settlement of claims through the GCCF was replaced by the court supervised settlement program.

The Deepwater Horizon oil spill was discovered on the afternoon of 22 April 2010 when a large oil slick began to spread at the former rig site. According to the Flow Rate Technical Group, the leak amounted to about 4.9 million barrels of oil, exceeding the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill as the largest ever to originate in U.S.-controlled waters and the 1979 Ixtoc I oil spill as the largest spill in the Gulf of Mexico. BP has challenged this calculation saying that it is overestimated as it includes over 810,000 barrels of oil which was collected before it could enter the Gulf waters.

The Deepwater Horizon oil spill occurred between 10 April and 19 September 2010 in the Gulf of Mexico. A variety of techniques were used to address fundamental strategies for addressing the spilled oil, which were: to contain oil on the surface, dispersal, and removal. While most of the oil drilled off Louisiana is a lighter crude, the leaking oil was of a heavier blend which contained asphalt-like substances. According to Ed Overton, who heads a federal chemical hazard assessment team for oil spills, this type of oil emulsifies well. Once it becomes emulsified, it no longer evaporates as quickly as regular oil, does not rinse off as easily, cannot be broken down by microbes as easily, and does not burn as well. "That type of mixture essentially removes all the best oil clean-up weapons", Overton said.