Related Research Articles

Caenorhabditis elegans is a free-living transparent nematode about 1 mm in length that lives in temperate soil environments. It is the type species of its genus. The name is a blend of the Greek caeno- (recent), rhabditis (rod-like) and Latin elegans (elegant). In 1900, Maupas initially named it Rhabditides elegans. Osche placed it in the subgenus Caenorhabditis in 1952, and in 1955, Dougherty raised Caenorhabditis to the status of genus.

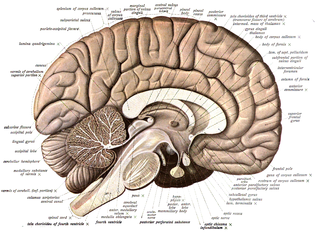

Neuroanatomy is the study of the structure and organization of the nervous system. In contrast to animals with radial symmetry, whose nervous system consists of a distributed network of cells, animals with bilateral symmetry have segregated, defined nervous systems. Their neuroanatomy is therefore better understood. In vertebrates, the nervous system is segregated into the internal structure of the brain and spinal cord and the series of nerves that connect the CNS to the rest of the body. Breaking down and identifying specific parts of the nervous system has been crucial for figuring out how it operates. For example, much of what neuroscientists have learned comes from observing how damage or "lesions" to specific brain areas affects behavior or other neural functions.

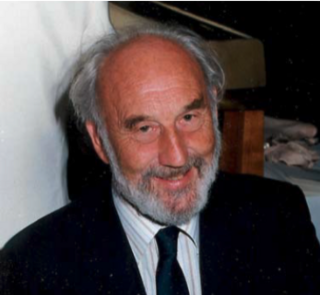

Sydney Brenner was a South African biologist. In 2002, he shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with H. Robert Horvitz and Sir John E. Sulston. Brenner made significant contributions to work on the genetic code, and other areas of molecular biology while working in the Medical Research Council (MRC) Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, England. He established the roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans as a model organism for the investigation of developmental biology, and founded the Molecular Sciences Institute in Berkeley, California, United States.

Sir John Cowdery Kendrew, was an English biochemist, crystallographer, and science administrator. Kendrew shared the 1962 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Max Perutz, for their work at the Cavendish Laboratory to investigate the structure of haem-containing proteins.

Howard Robert Horvitz ForMemRS NAS AAA&S APS NAM is an American biologist best known for his research on the nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans, for which he was awarded the 2002 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, together with Sydney Brenner and John E. Sulston, whose "seminal discoveries concerning the genetic regulation of organ development and programmed cell death" were "important for medical research and have shed new light on the pathogenesis of many diseases".

Sir John Edward Sulston was a British biologist and academic who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on the cell lineage and genome of the worm Caenorhabditis elegans in 2002 with his colleagues Sydney Brenner and Robert Horvitz at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology. He was a leader in human genome research and Chair of the Institute for Science, Ethics and Innovation at the University of Manchester. Sulston was in favour of science in the public interest, such as free public access of scientific information and against the patenting of genes and the privatisation of genetic technologies.

The Medical Research Council (MRC) Laboratory of Molecular Biology (LMB) is a research institute in Cambridge, England, involved in the revolution in molecular biology which occurred in the 1950–60s. Since then it has remained a major medical research laboratory at the forefront of scientific discovery, dedicated to improving the understanding of key biological processes at atomic, molecular and cellular levels using multidisciplinary methods, with a focus on using this knowledge to address key issues in human health.

Apoptosis is the process of programmed cell death. From its early conceptual beginnings in the 1950s, it has exploded as an area of research within the life sciences community. As well as its implication in many diseases, it is an integral part of biological development.

John Graham White is an Emeritus Professor of Anatomy and Molecular Biology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. His research interests are in the biology of the model organism Caenorhabditis elegans and laser microscopy.

Most animal testing involves invertebrates, especially Drosophila melanogaster, a fruit fly, and Caenorhabditis elegans, a nematode. These animals offer scientists many advantages over vertebrates, including their short life cycle, simple anatomy and the ease with which large numbers of individuals may be studied. Invertebrates are often cost-effective, as thousands of flies or nematodes can be housed in a single room.

Barbara J. Meyer is a biologist and genetist, noted for her pioneering research on lambda phage, a virus that infects bacteria; discovery of the master control gene involved in sex determination; and studies of gene regulation, particularly dosage compensation. Meyer's work has revealed mechanisms of sex determination and dosage compensation—that balance X-chromosome gene expression between the sexes in Caenorhabditis elegans that continue to serve as the foundation of diverse areas of study on chromosome structure and function today.

The nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans was first studied in the laboratory by Victor Nigon and Ellsworth Dougherty in the 1940s, but came to prominence after being adopted by Sydney Brenner in 1963 as a model organism for the study of developmental biology using genetics. In 1974, Brenner published the results of his first genetic screen, which isolated hundreds of mutants with morphological and functional phenotypes, such as being uncoordinated. In the 1980s, John Sulston and co-workers identified the lineage of all 959 cells in the adult hermaphrodite, the first genes were cloned, and the physical map began to be constructed. In 1998, the worm became the first multi-cellular organism to have its genome sequenced. Notable research using C. elegans includes the discoveries of caspases, RNA interference, and microRNAs. Six scientists have won the Nobel prize for their work on C. elegans.

Robert Hugh "Bob" Waterston, is an American biologist. He is best known for his work on the Human Genome Project, for which he was a pioneer along with John Sulston.

Neuroheuristics studies the dynamic relations within neuroscientific knowledge, using a transdisciplinary studies approach. It was proposed by Alessandro Villa in 2000.

OpenWorm is an international open science project for the purpose of simulating the roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans at the cellular level. Although the long-term goal is to model all 959 cells of the C. elegans, the first stage is to model the worm's locomotion by simulating the 302 neurons and 95 muscle cells. This bottom up simulation is being pursued by the OpenWorm community.

Julie Ann Ahringer is an American/British Professor of Genetics and Genomics, Director of the Gurdon Institute and a member of the Department of Genetics at the University of Cambridge. She leads a research lab investigating the control of gene expression.

Caenorhabditis elegans- microbe interactions are defined as any interaction that encompasses the association with microbes that temporarily or permanently live in or on the nematode C. elegans. The microbes can engage in a commensal, mutualistic or pathogenic interaction with the host. These include bacterial, viral, unicellular eukaryotic, and fungal interactions. In nature C. elegans harbours a diverse set of microbes. In contrast, C. elegans strains that are cultivated in laboratories for research purposes have lost the natural associated microbial communities and are commonly maintained on a single bacterial strain, Escherichia coli OP50. However, E. coli OP50 does not allow for reverse genetic screens because RNAi libraries have only been generated in strain HT115. This limits the ability to study bacterial effects on host phenotypes. The host microbe interactions of C. elegans are closely studied because of their orthologs in humans. Therefore, the better we understand the host interactions of C. elegans the better we can understand the host interactions within the human body.

Neural circuit reconstruction is the reconstruction of the detailed circuitry of the nervous system of an animal. It is sometimes called EM reconstruction since the main method used is the electron microscope (EM). This field is a close relative of reverse engineering of human-made devices, and is part of the field of connectomics, which in turn is a sub-field of neuroanatomy.

Worm bagging is a form of vivipary observed in nematodes, namely Caenorhabditis elegans. The process is characterized by eggs hatching within the parent and the larvae proceeding to consume and emerge from the parent.

Warwick Llewellyn Nicholas (1926–2010) was an Australian zoologist known as a pioneer in the field of nematology. He was a foundational member of the Australian Society for Parasitology (ASP) and in 1964, he organised the first ASP meeting. He became President of the Society in 1978, before being an elected Fellow from 1979.

References

- 1 2 Emmons, Scott W. (2015-04-19). "The beginning of connectomics: a commentary on White et al. (1986) 'The structure of the nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans'". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 370 (1666): 20140309. doi:10.1098/rstb.2014.0309. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 4360118 . PMID 25750233.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ankeny, Rachel A. (June 2001). "The natural history of Caenorhabditis elegans research". Nature Reviews Genetics. 2 (6): 474–479. doi:10.1038/35076538. ISSN 1471-0064. PMID 11389464. S2CID 10015950.

- 1 2 3 Brown, Andrew, 1955- (2004). In the beginning was the worm : finding the secrets of life in a tiny hermaphrodite. Pocket. ISBN 0-7434-1598-1. OCLC 53388833.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 Finch, John (2013-11-11). A Nobel Fellow on Every Floor: A History of the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology. Icon Books. ISBN 978-1-84831-670-6.

- ↑ Kirk, Rebecca (August 2014). "The first of its kind". Nature. 511 (7509): 13. doi: 10.1038/nature13360 . ISSN 1476-4687.

- 1 2 3 "Getting into the mind of a worm—a personal view". www.wormbook.org. Retrieved 2020-02-14.

- ↑ White, John Graham; Southgate, Eileen; Thomson, J. N.; Brenner, Sydney (1986-11-12). "The structure of the nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. B, Biological Sciences. 314 (1165): 1–340. doi:10.1098/rstb.1986.0056. PMID 22462104.

- ↑ Lewin, R. (1984-07-13). "The continuing tale of a small worm". Science. 225 (4658): 153–156. doi:10.1126/science.6729473. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 6729473.