The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is the UN process for negotiating an agreement to limit dangerous climate change. It is an international treaty among countries to combat "dangerous human interference with the climate system". The main way to do this is limiting the increase in greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. It was signed in 1992 by 154 states at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), informally known as the Earth Summit, held in Rio de Janeiro. The treaty entered into force on 21 March 1994. "UNFCCC" is also the name of the Secretariat charged with supporting the operation of the convention, with offices on the UN Campus in Bonn, Germany.

Just transition is a framework developed by the trade union movement to encompass a range of social interventions needed to secure workers' rights and livelihoods when economies are shifting to sustainable production, primarily combating climate change and protecting biodiversity. In Europe, advocates for a just transition want to unite social and climate justice, for example, for coal workers in coal-dependent developing regions who lack employment opportunities beyond coal.

The 2010 United Nations Climate Change Conference was held in Cancún, Mexico, from 29 November to 10 December 2010. The conference is officially referred to as the 16th session of the Conference of the Parties (COP 16) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the 6th session of the Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties (CMP 6) to the Kyoto Protocol. In addition, the two permanent subsidiary bodies of the UNFCCC — the Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA) and the Subsidiary Body for Implementation (SBI) — held their 33rd sessions. The 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference extended the mandates of the two temporary subsidiary bodies, the Ad Hoc Working Group on Further Commitments for Annex I Parties under the Kyoto Protocol (AWG-KP) and the Ad Hoc Working Group on Long-term Cooperative Action under the Convention (AWG-LCA), and they met as well.

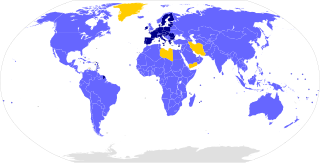

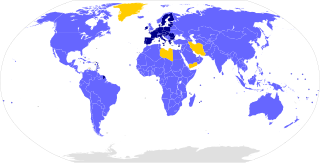

The Paris Agreement is an international treaty on climate change that was adopted in 2015. The treaty covers climate change mitigation, adaptation, and finance. The Paris Agreement was negotiated by 196 parties at the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference near Paris, France. As of February 2023, 195 members of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) are parties to the agreement. Of the three UNFCCC member states which have not ratified the agreement, the only major emitter is Iran. The United States withdrew from the agreement in 2020, but rejoined in 2021.

The Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI) is a scoring system designed by the German environmental and development organisation Germanwatch e.V. to enhance transparency in international climate politics. On the basis of standardised criteria, the index evaluates and compares the climate protection performance of 63 countries and the European Union (EU), which are together responsible for more than 90% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

The United Nations Climate Change Conferences are yearly conferences held in the framework of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). They serve as the formal meeting of the UNFCCC parties – the Conference of the Parties (COP) – to assess progress in dealing with climate change, and beginning in the mid-1990s, to negotiate the Kyoto Protocol to establish legally binding obligations for developed countries to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. Starting in 2005 the conferences have also served as the "Conference of the Parties Serving as the Meeting of Parties to the Kyoto Protocol" (CMP); also parties to the convention that are not parties to the protocol can participate in protocol-related meetings as observers. From 2011 to 2015 the meetings were used to negotiate the Paris Agreement as part of the Durban platform, which created a general path towards climate action. Any final text of a COP must be agreed by consensus.

The nationally determined contributions (NDCs) are commitments that countries make to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions as part of climate change mitigation. The plans that countries make also include policies and measures that they plan to implement as a contribution to achieve the global targets set out in the Paris Agreement. NDCs play a central role in guiding countries toward achieving these temperature targets.

The 2016 United Nations Climate Change Conference was an international meeting of political leaders and activists to discuss environmental issues. It was held in Marrakech, Morocco, on 7–18 November 2016. The conference incorporated the twenty-second Conference of the Parties (COP22), the twelfth meeting of the parties to the Kyoto Protocol (CMP12), and the first meeting of the parties to the Paris Agreement (CMA1). The purpose of the conference was to discuss and implement plans about combatting climate change and to "[demonstrate] to the world that the implementation of the Paris Agreement is underway". Participants work together to come up with global solutions to climate change.

Action for Climate Empowerment (ACE) is a term adopted by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). It refers to Article 6 of the Convention's original text (1992), focusing on six priority areas: education, training, public awareness, public participation, public access to information, and international cooperation on these issues. The implementation of all six areas has been identified as the pivotal factor for everyone to understand and participate in solving the complex challenges presented by climate change. The importance of ACE is reflected in other international frameworks such as the Sustainable Development Goals ; the Global Action Programme for Education for Sustainable Development ; the Aarhus Convention (2011); the Escazú Agreement (2018) and the Bali Guidelines (2010).

The 2017 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP23) was an international meeting of political leaders, non-state actors and activists to discuss environmental issues. It was held at UN Campus in Bonn, Germany, during 6–17 November 2017. The conference incorporated the 23rd Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the thirteenth meeting of the parties for the Kyoto Protocol (CMP13), and the second session of the first meeting of the parties for the Paris Agreement.

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement on climate change enables Parties to cooperate in implementing their nationally determined contributions (NDCs). Among other things, this means that emission reductions can be transferred between countries and counted towards NDCs. Agreement on the provisions of Article 6 was reached after intensive negotiations lasting several years.

The Talanoa Dialogue was a process designed to help countries implement and enhance their Nationally Determined Contributions by 2020. The Dialogue was mandated by the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention for Climate Change to take stock of the collective global efforts to reduce the emissions of greenhouse gases, in line with the goals of the Paris Agreement, which is to limit the rise in average global temperature to 2°C (3.6°F) above pre-industrial levels, and to pursue efforts to limit the increase to 1.5°C (2.7°F).

The 2018 United Nations Climate Change Conference, more commonly referred to as the Katowice Climate Change Conference or COP24, was the 24th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. It was held between 2 and 15 December 2018 in Katowice, Poland. The conference was held in the International Congress Centre. The president of COP24 was Michał Kurtyka. The conference also incorporated the fourteenth meeting of the parties for the Kyoto Protocol (CMP14), and the third session of the first meeting of the parties for the Paris Agreement which agreed on rules to implement the Agreement. The conference's objective was to have a full implementation of the Paris agreement.

The 2019 United Nations Climate Change Conference, also known as COP25, was the 25th United Nations Climate Change conference. It was held in Madrid, Spain, from 2 to 13 December 2019 under the presidency of the Chilean government. The conference incorporated the 25th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the 15th meeting of the parties to the Kyoto Protocol (CMP15), and the second meeting of the parties to the Paris Agreement (CMA2).

The Global Stocktake is a fundamental component of the Paris Agreement which is used to monitor its implementation and evaluate the collective progress made in achieving the agreed goals. The Global Stocktake thus links implementation of nationally determined contributions (NDCs) with the overarching goals of the Paris Agreement, and has the ultimate aim of raising climate ambition.

Sustainable Development Goal 13 is to limit and adapt to climate change. It is one of 17 Sustainable Development Goals established by the United Nations General Assembly in 2015. The official mission statement of this goal is to "Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts". SDG 13 and SDG 7 on clean energy are closely related and complementary.

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the Paris Agreement, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) are connected through their common goals of addressing global challenges and promoting sustainable development through policies and international cooperation.

Pledge and review is a method for facilitating international action against climate change. It involves nations each making a self-determined pledge relating to actions they expect to take in response to global warming, which they submit to the United Nations. Some time after the pledges have been submitted, there is a review process where nations assess each other's progress towards meeting the pledges. Then a further round of enhanced pledges can be made, and the process can further iterate.

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) is an outcome of the 2022 United Nations Biodiversity Conference. Its tentative title had been the "Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework". The GBF was adopted by the 15th Conference of Parties (COP15) to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) on 19 December 2022. It has been promoted as a "Paris Agreement for Nature". It is one of a handful of agreements under the auspices of the CBD, and it is the most significant to date. It has been hailed as a "huge, historic moment" and a "major win for our planet and for all of humanity."