Entamoeba is a genus of Amoebozoa found as internal parasites or commensals of animals. In 1875, Fedor Lösch described the first proven case of amoebic dysentery in St. Petersburg, Russia. He referred to the amoeba he observed microscopically as Amoeba coli; however, it is not clear whether he was using this as a descriptive term or intended it as a formal taxonomic name. The genus Entamoeba was defined by Casagrandi and Barbagallo for the species Entamoeba coli, which is known to be a commensal organism. Lösch's organism was renamed Entamoeba histolytica by Fritz Schaudinn in 1903; he later died, in 1906, from a self-inflicted infection when studying this amoeba. For a time during the first half of the 20th century the entire genus Entamoeba was transferred to Endamoeba, a genus of amoebas infecting invertebrates about which little is known. This move was reversed by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature in the late 1950s, and Entamoeba has stayed 'stable' ever since.

Dysentery, historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications may include dehydration.

Entamoeba histolytica is an anaerobic parasitic amoebozoan, part of the genus Entamoeba. Predominantly infecting humans and other primates causing amoebiasis, E. histolytica is estimated to infect about 35-50 million people worldwide. E. histolytica infection is estimated to kill more than 55,000 people each year. Previously, it was thought that 10% of the world population was infected, but these figures predate the recognition that at least 90% of these infections were due to a second species, E. dispar. Mammals such as dogs and cats can become infected transiently, but are not thought to contribute significantly to transmission.

Isosporiasis, also known as cystoisosporiasis, is a human intestinal disease caused by the parasite Cystoisospora belli. It is found worldwide, especially in tropical and subtropical areas. Infection often occurs in immuno-compromised individuals, notably AIDS patients, and outbreaks have been reported in institutionalized groups in the United States. The first documented case was in 1915. It is usually spread indirectly, normally through contaminated food or water (CDC.gov).

Giardiasis is a parasitic disease caused by Giardia duodenalis. Infected individuals who experience symptoms may have diarrhoea, abdominal pain, and weight loss. Less common symptoms include vomiting and blood in the stool. Symptoms usually begin one to three weeks after exposure and, without treatment, may last two to six weeks or longer.

Amoebozoa is a major taxonomic group containing about 2,400 described species of amoeboid protists, often possessing blunt, fingerlike, lobose pseudopods and tubular mitochondrial cristae. In traditional classification schemes, Amoebozoa is usually ranked as a phylum within either the kingdom Protista or the kingdom Protozoa. In the classification favored by the International Society of Protistologists, it is retained as an unranked "supergroup" within Eukaryota. Molecular genetic analysis supports Amoebozoa as a monophyletic clade. Modern studies of eukaryotic phylogenetic trees identify it as the sister group to Opisthokonta, another major clade which contains both fungi and animals as well as several other clades comprising some 300 species of unicellular eukaryotes. Amoebozoa and Opisthokonta are sometimes grouped together in a high-level taxon, variously named Unikonta, Amorphea or Opimoda.

A trophozoite is the activated, feeding stage in the life cycle of certain protozoa such as malaria-causing Plasmodium falciparum and those of the Giardia group. The complementary form of the trophozoite state is the thick-walled cyst form. They are often different from the cyst stage, which is a protective, dormant form of the protozoa. Trophozoites are often found in the host's body fluids and tissues and in many cases, they are the form of the protozoan that causes disease in the host. In the protozoan, Entamoeba histolytica it invades the intestinal mucosa of its host, causing dysentery, which aid in the trophozoites traveling to the liver and leading to the production of hepatic abscesses.

Balantidiasis is a protozoan infection caused by infection with Balantidium coli.

Dientamoebiasis is a medical condition caused by infection with Dientamoeba fragilis, a single-cell parasite that infects the lower gastrointestinal tract of humans. It is an important cause of traveler's diarrhea, chronic abdominal pain, chronic fatigue, and failure to thrive in children.

Blastocystosis refers to a medical condition caused by infection with Blastocystis. Blastocystis is a protozoal, single-celled parasite that inhabits the gastrointestinal tracts of humans and other animals. Many different types of Blastocystis exist, and they can infect humans, farm animals, birds, rodents, amphibians, reptiles, fish, and even cockroaches. Blastocystosis has been found to be a possible risk factor for development of irritable bowel syndrome.

Protozoan infections are parasitic diseases caused by organisms formerly classified in the kingdom Protozoa. These organisms are now classified in the supergroups Excavata, Amoebozoa, Harosa, and Archaeplastida. They are usually contracted by either an insect vector or by contact with an infected substance or surface.

Amoebiasis, or amoebic dysentery, is an infection of the intestines caused by a parasitic amoeba Entamoeba histolytica. Amoebiasis can be present with no, mild, or severe symptoms. Symptoms may include lethargy, loss of weight, colonic ulcerations, abdominal pain, diarrhea, or bloody diarrhea. Complications can include inflammation and ulceration of the colon with tissue death or perforation, which may result in peritonitis. Anemia may develop due to prolonged gastric bleeding.

A amoebic liver abscess is a type of liver abscess caused by amebiasis. It is the involvement of liver tissue by trophozoites of the organism Entamoeba histolytica and of its abscess due to necrosis.

Amoebic brain abscess is an affliction caused by the anaerobic parasitic protist Entamoeba histolytica. It is extremely rare; the first case being reported in 1849. Brain abscesses resulting from Entamoeba histolytica are difficult to diagnose and very few case reports suggest complete recovery even after the administration of appropriate treatment regimen.

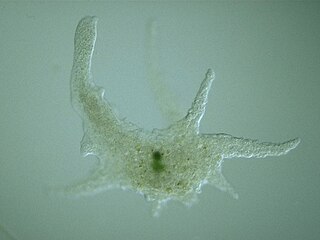

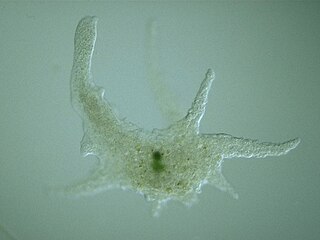

Sappinia is a genus of heterotrophic, lobose amoebae within the family Thecamoebidae. A defining feature of Sappinia, which separates it from its sister genus Thecamoeba, is the presence of two closely apposed nuclei with a central, flattened connection. Sappinia species have two life cycle stages: a trophozoite and a cyst. Up until 2015, only two species had been discovered, Sappinia pedata and Sappinia diploidea. Sequencing of the small subunit rRNA of a particular isolate from a sycamore tree revealed a new species, Sappinia platani.Sappinia species were once thought to be coprozoic, as the first strains were isolated from animal dung. More research has shown that they are typical free-living amoebae, and can be found worldwide in soil, plant litter, and standing decaying plants, as well as freshwater ponds. In 2001, the first and only case of human pathogenesis in Sappinia was confirmed. The patient was a non-immunocompromised 38-year-old male who presented signs of amoebic encephalitis and who patient made a full recovery after treatment with several antimicrobials. The CDC initially classified the causative agent as S. diploidea based on morphological characteristics, but in 2009, Qvarnstrom et al. used molecular data to confirm that the true causative agent was S. pedata.

Entamoeba polecki is an intestinal parasite of the genus Entamoeba. E. polecki is found primarily in pigs and monkeys and is largely considered non-pathogenic in humans, although there have been some reports regarding symptomatic infections of humans. Prevalence is concentrated in New Guinea, with distribution also recorded in areas of southeast Asia, France, and the United States.

Dientamoeba fragilis is a species of single-celled excavates found in the gastrointestinal tract of some humans, pigs and gorillas. It causes gastrointestinal upset in some people, but not in others. It is an important cause of traveller's diarrhoea, chronic diarrhoea, fatigue and, in children, failure to thrive. Despite this, its role as a "commensal, pathobiont, or pathogen" is still debated. D. fragilis is one of the smaller parasites that are able to live in the human intestine. Dientamoeba fragilis cells are able to survive and move in fresh feces but are sensitive to aerobic environments. They dissociate when in contact or placed in saline, tap water or distilled water.

Entamoeba moshkovskii is part of the genus Entamoeba. It is found in areas with polluted water sources, and is prevalent in places such as Malaysia, India, and Bangladesh, but more recently has made its way to Turkey, Australia, and North America. This amoeba is said to rarely infect humans, but recently this has changed. It is in question as to whether it is pathogenic or not. Despite some sources stating this is a free living amoeba, various studies worldwide have shown it contains the ability to infect humans, with some cases of pathogenic potential being reported. Some of the symptoms that often occur are diarrhea, weight loss, bloody stool, and abdominal pain. The first known human infection also known as the "Laredo strain" of Entamoebic mushkovskii was in Laredo, Texas in 1991, although it was first described by a man named Tshalaia in 1941 in Moscow, Russia. It is known to affect people of all ages and genders.

Entamoeba invadens is an amoebozoa parasite of reptiles, within the genus Entamoeba. It is closely related to the human parasite Entamoeba histolytica, causing similar invasive disease in reptiles, in addition to a similar morphology and lifecycle.

Naegleria fowleri, also known as the brain-eating amoeba, is a species of the genus Naegleria. It belongs to the phylum Percolozoa and is technically classified as an amoeboflagellate excavate, rather than a true amoeba. This free-living microorganism primarily feeds on bacteria but can become pathogenic in humans, causing an extremely rare, sudden, severe, and usually fatal brain infection known as naegleriasis or primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM).