Cloning is the process of producing individual organisms with identical genomes, either by natural or artificial means. In nature, some organisms produce clones through asexual reproduction; this reproduction of an organism by itself without a mate is known as parthenogenesis. In the field of biotechnology, cloning is the process of creating cloned organisms of cells and of DNA fragments.

Human cloning is the creation of a genetically identical copy of a human. The term is generally used to refer to artificial human cloning, which is the reproduction of human cells and tissue. It does not refer to the natural conception and delivery of identical twins. The possibilities of human cloning have raised controversies. These ethical concerns have prompted several nations to pass laws regarding human cloning.

A genetic chimerism or chimera is a single organism composed of cells with more than one distinct genotype. In animals and human chimeras, this means an individual derived from two or more zygotes, which can include possessing blood cells of different blood types, and subtle variations in form (phenotype). Animal chimeras are produced by the merger of two embryos. In plant chimeras, however, the distinct types of tissue may originate from the same zygote, and the difference is often due to mutation during ordinary cell division. Normally, genetic chimerism is not visible on casual inspection; however, it has been detected in the course of proving parentage. In contrast, an individual where each cell contains genetic material from two organisms of different breeds, varieties, species or genera is called a hybrid.

Clonaid is an American-based human cloning organization, registered as a company in the Bahamas. Founded in 1997, it has philosophical ties with the UFO religion Raëlism, which sees cloning as the first step in achieving immortality. On December 27, 2002, Clonaid's chief executive, Brigitte Boisselier, claimed that a baby clone, named Eve, was born. Media coverage of the claim sparked serious criticism and ethical debate that lasted more than a year. Florida attorney Bernard Siegel tried to appoint a special guardian for Eve and threatened to sue Clonaid, because he was afraid that the child might be treated like a lab rat. Siegel, who heard the company's actual name was not Clonaid, decided that the Clonaid project was a sham. Bioethicist Clara Alto condemned Clonaid for premature human experimentation and noted the high incidence of malformations and thousands of fetal deaths in animal cloning.

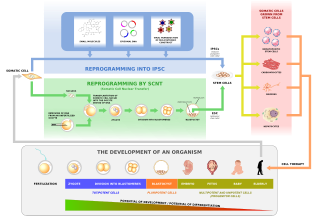

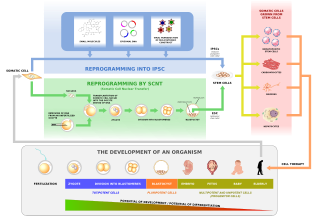

In genetics and developmental biology, somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) is a laboratory strategy for creating a viable embryo from a body cell and an egg cell. The technique consists of taking an denucleated oocyte and implanting a donor nucleus from a somatic (body) cell. It is used in both therapeutic and reproductive cloning. In 1996, Dolly the sheep became famous for being the first successful case of the reproductive cloning of a mammal. In January 2018, a team of scientists in Shanghai announced the successful cloning of two female crab-eating macaques from foetal nuclei.

Xenotransplantation, or heterologous transplant, is the transplantation of living cells, tissues or organs from one species to another. Such cells, tissues or organs are called xenografts or xenotransplants. It is contrasted with allotransplantation, syngeneic transplantation or isotransplantation and autotransplantation. Xenotransplantation is an artificial method of creating an animal-human chimera, that is, a human with a subset of animal cells. In contrast, an individual where each cell contains genetic material from a human and an animal is called a human–animal hybrid.

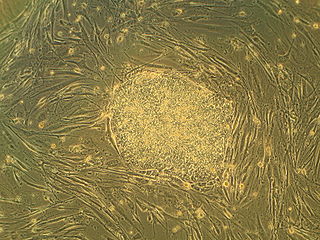

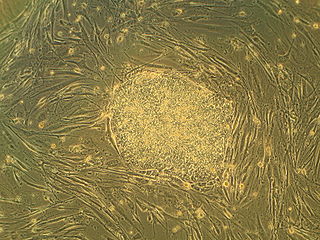

Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are pluripotent stem cells derived from the inner cell mass of a blastocyst, an early-stage pre-implantation embryo. Human embryos reach the blastocyst stage 4–5 days post fertilization, at which time they consist of 50–150 cells. Isolating the inner cell mass (embryoblast) using immunosurgery results in destruction of the blastocyst, a process which raises ethical issues, including whether or not embryos at the pre-implantation stage have the same moral considerations as embryos in the post-implantation stage of development.

Commercial animal cloning is the cloning of animals for commercial purposes, including animal husbandry, medical research, competition camels and horses, pet cloning, and restoring populations of endangered and extinct animals. The practice was first demonstrated in 1996 with Dolly the sheep.

A designer baby is a baby whose genetic makeup has been selected or altered, often to exclude a particular gene or to remove genes associated with disease. This process usually involves analysing a wide range of human embryos to identify genes associated with particular diseases and characteristics, and selecting embryos that have the desired genetic makeup; a process known as preimplantation genetic diagnosis. Screening for single genes is commonly practiced, and polygenic screening is offered by a few companies. Other methods by which a baby's genetic information can be altered involve directly editing the genome before birth, which is not routinely performed and only one instance of this is known to have occurred as of 2019, where Chinese twins Lulu and Nana were edited as embryos, causing widespread criticism.

Christians take multiple positions in the debate on the morality of human cloning. Since Dolly the sheep was successfully cloned on 5 July 1996, and the possibility of cloning humans became a reality, Christian leaders have been pressed to take an ethical stance on its morality. While many Christians tend to disagree with the practice, such as Roman Catholics and a majority of fundamentalist pastors, including Southern Baptists, the views taken by various other Christian denominations are diverse and often conflicting. It is hard to pinpoint any one, definite stance of the Christian religion, since there are so many Christian denominations and so few official statements from each of them concerning the morality of human cloning.

A biopharmaceutical, also known as a biological medical product, or biologic, is any pharmaceutical drug product manufactured in, extracted from, or semisynthesized from biological sources. Different from totally synthesized pharmaceuticals, they include vaccines, whole blood, blood components, allergenics, somatic cells, gene therapies, tissues, recombinant therapeutic protein, and living medicines used in cell therapy. Biologics can be composed of sugars, proteins, nucleic acids, or complex combinations of these substances, or may be living cells or tissues. They are isolated from living sources—human, animal, plant, fungal, or microbial. They can be used in both human and animal medicine.

Axel Kahn was a French scientist and geneticist. He was the brother of the journalist Jean-François Kahn and the chemist Olivier Kahn. He was a member of the French National Consultative Ethics Committee from 1992 to 2004 and worked in gene therapy. He first entered the INSERM with a specialization in biochemistry. He was named in 2002 as a counsellor for biosciences and biotechnologies matters by the European Commission. Head of French laboratories specialized in biomedical sciences between years 1984 and 2007, he was elected President of the Paris Descartes University in December 2007, as the sole candidate.

The stem cell controversy concerns the ethics of research involving the development and use of human embryos. Most commonly, this controversy focuses on embryonic stem cells. Not all stem cell research involves human embryos. For example, adult stem cells, amniotic stem cells, and induced pluripotent stem cells do not involve creating, using, or destroying human embryos, and thus are minimally, if at all, controversial. Many less controversial sources of acquiring stem cells include using cells from the umbilical cord, breast milk, and bone marrow, which are not pluripotent.

Stem cell laws are the law rules, and policy governance concerning the sources, research, and uses in treatment of stem cells in humans. These laws have been the source of much controversy and vary significantly by country. In the European Union, stem cell research using the human embryo is permitted in Sweden, Spain, Finland, Belgium, Greece, Britain, Denmark and the Netherlands; however, it is illegal in Germany, Austria, Ireland, Italy, and Portugal. The issue has similarly divided the United States, with several states enforcing a complete ban and others giving support. Elsewhere, Japan, India, Iran, Israel, South Korea, China, and Australia are supportive. However, New Zealand, most of Africa, and most of South America are restrictive.

Mitochondrial replacement therapy (MRT), sometimes called mitochondrial donation, is the replacement of mitochondria in one or more cells to prevent or ameliorate disease. MRT originated as a special form of in vitro fertilisation in which some or all of the future baby's mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) comes from a third party. This technique is used in cases when mothers carry genes for mitochondrial diseases. The therapy is approved for use in the United Kingdom. A second application is to use autologous mitochondria to replace mitochondria in damaged tissue to restore the tissue to a functional state. This has been used in clinical research in the United States to treat cardiac-compromised newborns.

Cryoconservation of animal genetic resources is a strategy wherein samples of animal genetic materials are preserved cryogenically.

Jan Deckers works in bioethics at Newcastle University. His work revolves mainly around three topics: animal ethics, reproductive ethics and embryo research, and ethics of genetics.

Human germline engineering is the process by which the genome of an individual is edited in such a way that the change is heritable. This is achieved by altering the genes of the germ cells, which then mature into genetically modified eggs and sperm. For safety, ethical, and social reasons, there is broad agreement among the scientific community and the public that germline editing for reproduction is a red line that should not be crossed at this point in time. There are differing public sentiments, however, on whether it may be performed in the future depending on whether the intent would be therapeutic or non-therapeutic.

The He Jiankui affair is a scientific and bioethical controversy concerning the use of genome editing following its first use on humans by Chinese scientist He Jiankui, who edited the genomes of human embryos in 2018. He became widely known on 26 November 2018 after he announced that he had created the first human genetically edited babies. He was listed in the Time's 100 most influential people of 2019. The affair led to ethical and legal controversies, resulting in the indictment of He and two of his collaborators, Zhang Renli and Qin Jinzhou. He eventually received widespread international condemnation.

The Hwang affair, or Hwang scandal, or Hwanggate, is a case of scientific misconduct and ethical issues surrounding a South Korean biologist, Hwang Woo-suk, who claimed to have created the first human embryonic stem cells by cloning in 2004. Hwang and his research team at the Seoul National University reported in the journal Science that they successfully developed a somatic cell nuclear transfer method with which they made the stem cells. In 2005, they published again in Science the successful cloning of 11 person-specific stem cells using 185 human eggs. The research was hailed as "a ground-breaking paper" in science. Hwang was elevated as "the pride of Korea", "national hero" [of Korea], and a "supreme scientist", to international praise and fame. Recognitions and honours immediately followed, including South Korea's Presidential Award in Science and Technology, and Time magazine listing him among the "People Who Mattered 2004" and the most influential people "The 2004 Time 100".