Electronic Facial Identification Technique is a computer-based method of producing facial composites of wanted criminals, based on eyewitness descriptions.

A facial recognition system is a technology potentially capable of matching a human face from a digital image or a video frame against a database of faces. Such a system is typically employed to authenticate users through ID verification services, and works by pinpointing and measuring facial features from a given image.

Computer forensics is a branch of digital forensic science pertaining to evidence found in computers and digital storage media. The goal of computer forensics is to examine digital media in a forensically sound manner with the aim of identifying, preserving, recovering, analyzing and presenting facts and opinions about the digital information.

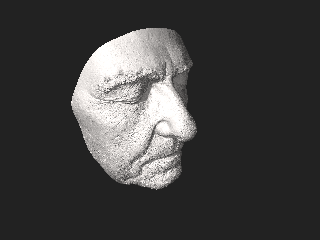

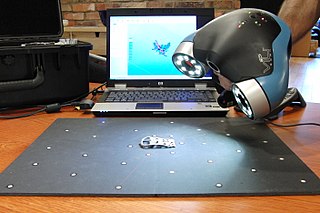

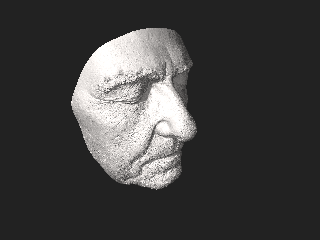

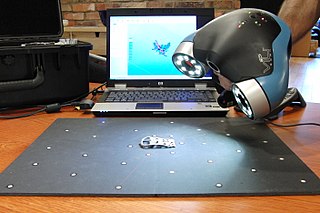

Three-dimensional face recognition is a modality of facial recognition methods in which the three-dimensional geometry of the human face is used. It has been shown that 3D face recognition methods can achieve significantly higher accuracy than their 2D counterparts, rivaling fingerprint recognition.

3D scanning is the process of analyzing a real-world object or environment to collect three dimensional data of its shape and possibly its appearance. The collected data can then be used to construct digital 3D models.

Software visualization or software visualisation refers to the visualization of information of and related to software systems—either the architecture of its source code or metrics of their runtime behavior—and their development process by means of static, interactive or animated 2-D or 3-D visual representations of their structure, execution, behavior, and evolution.

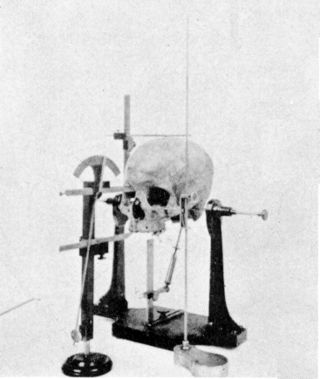

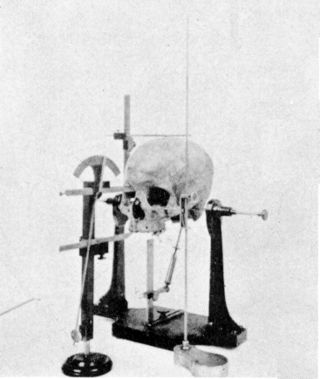

Forensic facial reconstruction is the process of recreating the face of an individual from their skeletal remains through an amalgamation of artistry, anthropology, osteology, and anatomy. It is easily the most subjective—as well as one of the most controversial—techniques in the field of forensic anthropology. Despite this controversy, facial reconstruction has proved successful frequently enough that research and methodological developments continue to be advanced.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to forensic science:

Wilhelm His Sr. was a Swiss anatomist and professor who invented the microtome. By treating animal tissue with acids and salts to harden it and then slicing it very thinly with the microtome, scientists were able to further study the organization and function of tissues and cells under a microscope.

Cephalometry is the study and measurement of the head, usually the human head, especially by medical imaging such as radiography. Craniometry, the measurement of the cranium (skull), is a large subset of cephalometry. Cephalometry also has a history in phrenology, which is the study of personality and character as well as physiognomy, which is the study of facial features. Cephalometry as applied in a comparative anatomy context informs biological anthropology. In clinical contexts such as dentistry and oral and maxillofacial surgery, cephalometric analysis helps in treatment and research; cephalometric landmarks guide surgeons in planning and operating.

Myrtis is the name given by archaeologists to an 11-year-old girl from ancient Athens, whose remains were discovered in 1994–95 in a mass grave during work to build the metro station at Kerameikos, Greece. The name was chosen from common ancient Greek names. The analysis showed that Myrtis and two other bodies in the mass grave had died of typhoid fever during the Plague of Athens in 430 BC.

Karen T. Taylor is an American forensic and portrait artist who has worked to help resolve criminal cases for a variety of law enforcement agencies throughout the world. Her primary expertise includes composite imagery, child and adult age progression, postmortem drawing and forensic facial reconstruction. In the mid-1980s, Taylor pioneered the method of 2-dimensional facial reconstruction, by drawing facial features over frontal and lateral skull photographs based on anthropological data. Taylor is also well-established as a forensic art educator, fine art portrait sculptor, and specialist in the human face.

Forensic art is any art used in law enforcement or legal proceedings. Forensic art is used to assist law enforcement with the visual aspects of a case, often using witness descriptions and video footage.

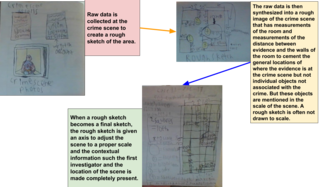

Computational criminology is an interdisciplinary field which uses computing science methods to formally define criminology concepts, improve our understanding of complex phenomena, and generate solutions for related problems.

Caroline M. Wilkinson is a British anthropologist and academic, who specialises in forensic facial reconstruction. She has been a professor at the Liverpool John Moores University's School of Art and Design since 2014. She is best known for her work in forensic facial reconstruction and has been a contributor to many television programmes on the subject, as well as the creator of reconstructed heads of kings Richard III of England in 2013 and Robert the Bruce of Scotland in 2016.

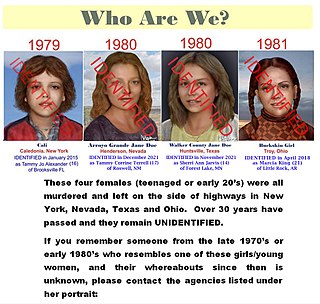

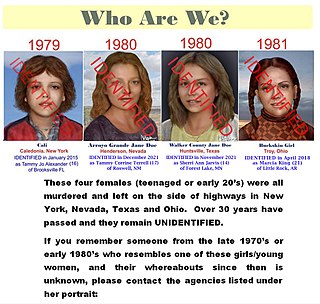

Unidentified decedent, or unidentified person, is a corpse of a person whose identity cannot be established by police and medical examiners. In many cases, it is several years before the identities of some UIDs are found, while in some cases, they are never identified. A UID may remain unidentified due to lack of evidence as well as absence of personal identification such as a driver's license. Where the remains have deteriorated or been mutilated to the point that the body is not easily recognized, a UID's face may be reconstructed to show what they had looked like before death. UIDs are often referred to by the placeholder names "John Doe" or "Jane Doe". In a database maintained by the Ontario Provincial Police of 371 unidentified decedents found between 1964 and 2015, 369 were male and two were female.

DNA phenotyping is the process of predicting an organism's phenotype using only genetic information collected from genotyping or DNA sequencing. This term, also known as molecular photofitting, is primarily used to refer to the prediction of a person's physical appearance and/or biogeographic ancestry for forensic purposes.

Betty Patricia Gatliff was an American pioneer in the field of forensic art and forensic facial reconstruction. Working closely with forensic anthropologist Dr. Clyde Snow, she sculpturally reconstructed faces of individuals including the Pharaoh Tutankhamun, President John F. Kennedy, and the unidentified victims of serial killer John Wayne Gacy.

Identity replacement technology is any technology that is used to cover up all or parts of a person's identity, either in real life or virtually. This can include face masks, face authentication technology, and deepfakes on the Internet that spread fake editing of videos and images. Face replacement and identity masking are used by either criminals or law-abiding citizens. Identity replacement tech, when operated on by criminals, leads to heists or robbery activities. Law-abiding citizens utilize identity replacement technology to prevent government or various entities from tracking private information such as locations, social connections, and daily behaviors.

Mary Huffman Manhein is an American forensic anthropologist. Nicknamed The Bone Lady, she was the founding director of the Forensic Anthropology and Computer Enhancement Services (FACES) laboratory at Louisiana State University (LSU) in 1990, and of the Louisiana Repository for Unidentified and Missing Persons Information Program in 2006. The repository is considered the "most comprehensive statewide database of its kind".