Angels have appeared in works of art since early Christian art, and they have been a popular subject for Byzantine and European paintings and sculpture.

Mary Magdalene was a woman who, according to the four canonical gospels, traveled with Jesus as one of his followers and was a witness to his crucifixion and resurrection. She is mentioned by name twelve times in the canonical gospels, more than most of the apostles and more than any other woman in the gospels, other than Jesus's family. Mary's epithet Magdalene may be a toponymic surname, meaning that she came from the town of Magdala, a fishing town on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee in Roman Judea.

An altarpiece is an artwork such as a painting, sculpture or relief representing a religious subject made for placing at the back of or behind the altar of a Christian church. Though most commonly used for a single work of art such as a painting or sculpture, or a set of them, the word can also be used of the whole ensemble behind an altar, otherwise known as a reredos, including what is often an elaborate frame for the central image or images. Altarpieces were one of the most important products of Christian art especially from the late Middle Ages to the era of the Counter-Reformation.

The Ghent Altarpiece, also called the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, is a very large and complex 15th-century polyptych altarpiece in St Bavo's Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium. It was begun around the mid-1420s and completed by 1432, and it is attributed to the Early Netherlandish painters and brothers Hubert and Jan van Eyck. The altarpiece is considered a masterpiece of European art and one of the world's treasures, it was "the first major oil painting", and it marked the transition from Middle Age to Renaissance art.

Matthias Grünewald was a German Renaissance painter of religious works who ignored Renaissance classicism to continue the style of late medieval Central European art into the 16th century. His first name is also given as Mathis and his surname as Gothart or Neithardt.

The Isenheim Altarpiece is an altarpiece sculpted and painted by, respectively, the Germans Nikolaus of Haguenau and Matthias Grünewald in 1512–1516. It is on display at the Unterlinden Museum at Colmar, Alsace, in France. It is Grünewald's largest work and is regarded as his masterpiece. It was painted for the Monastery of St. Anthony in Issenheim near Colmar, which specialized in hospital work. The Antonine monks of the monastery were noted for their care of plague sufferers as well as for their treatment of skin diseases, such as ergotism. The image of the crucified Christ is pitted with plague-type sores, showing patients that Jesus understood and shared their afflictions. The veracity of the work's depictions of medical conditions was unusual in the history of European art.

The Maestà, or Maestà of Duccio, is an altarpiece composed of many individual paintings commissioned by the city of Siena in 1308 from the artist Duccio di Buoninsegna and is his most famous work. The front panels make up a large enthroned Madonna and Child with saints and angels, and a predella of the Childhood of Christ with prophets. The reverse has the rest of a combined cycle of the Life of the Virgin and the Life of Christ in a total of forty-three small scenes; several panels are now dispersed or lost. The base of the panel has an inscription that reads : "Holy Mother of God, be thou the cause of peace for Siena and life to Duccio because he painted thee thus." Though it took a generation for its effect to be truly felt, Duccio's Maestà set Italian painting on a course leading away from the hieratic representations of Byzantine art towards more direct presentations of reality.

The Beaune Altarpiece is a large polyptych c. 1445–1450 altarpiece by the Early Netherlandish artist Rogier van der Weyden, painted in oil on oak panels with parts later transferred to canvas. It consists of fifteen paintings on nine panels, of which six are painted on both sides. Unusually for the period, it retains some of its original frames.

The Coronation of the Virgin or Coronation of Mary is a subject in Christian art, especially popular in Italy in the 13th to 15th centuries, but continuing in popularity until the 18th century and beyond. Christ, sometimes accompanied by God the Father and the Holy Spirit in the form of a dove, places a crown on the head of Mary as Queen of Heaven. In early versions the setting is a Heaven imagined as an earthly court, staffed by saints and angels; in later versions Heaven is more often seen as in the sky, with the figures seated on clouds. The subject is also notable as one where the whole Christian Trinity is often shown together, sometimes in unusual ways. Crowned Virgins are also seen in Eastern Orthodox Christian icons, specifically in the Russian Orthodox church after the 18th century. Mary is sometimes shown, in both Eastern and Western Christian art, being crowned by one or two angels, but this is considered a different subject.

Damià Forment was a Valencian Spanish architect and sculptor, considered the most important Spanish sculptor of the 16th century.

Margaret Leonard Starbird is the author of seven books arguing for the existence of a secret Christian tradition that held Jesus was married to Mary Magdalene, calling it the "Grail heresy", after having set out to discredit the bloodline hypothesis contained in The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail.

The St. Cecilia Altarpiece is an oil painting by the Italian High Renaissance master Raphael. Completed in his later years, in around 1516–17, the painting depicts Saint Cecilia, the patron saint of musicians and Church music, listening to a choir of angels in the company of St. Paul, St. John the Evangelist, St. Augustine and Mary Magdalene. Commissioned for a church in Bologna, the painting now hangs in that city's Pinacoteca Nazionale. According to Giorgio Vasari the musical instruments strewn about Cecilia's feet were not painted by Raphael but by his student, Giovanni da Udine.

The Magdalen Reading is one of three surviving fragments of a large mid-15th-century oil-on-panel altarpiece by the Early Netherlandish painter Rogier van der Weyden. The panel, originally oak, was completed some time between 1435 and 1438 and has been in the National Gallery, London since 1860. It shows a woman with the pale skin, high cheek bones and oval eyelids typical of the idealised portraits of noble women of the period. She is identifiable as the Magdalen from the jar of ointment placed in the foreground, which is her traditional attribute in Christian art. She is presented as completely absorbed in her reading, a model of the contemplative life, repentant and absolved of past sins. In Catholic tradition the Magdalen was conflated with both Mary of Bethany who anointed the feet of Jesus with oil and the unnamed "sinner" of Luke 7:36–50. Iconography of the Magdalen commonly shows her with a book, in a moment of reflection, in tears, or with eyes averted.

The Annunciation has been one of the most frequent subjects of Christian art. Depictions of the Annunciation go back to early Christianity, with the Priscilla catacomb in Rome including the oldest known fresco of the Annunciation, dating to the 4th century.

The Penitent Magdalene is a painting of saint Mary Magdalene by Titian dating to around 1531, signed 'TITIANUS' on the ointment jar to the left. It is now in the Sala di Apollo of the Palazzo Pitti in Florence, Italy.

The Abbey of Santa Giustina is a 10th-century Benedictine abbey complex located in front of the Prato della Valle in central Padua, region of Veneto, Italy. Adjacent to the former monastery is the basilica church of Santa Giustina, initially built in the 6th century, but whose present form derives from a 17th-century reconstruction.

Archangel Michael may be depicted in Christian art alone or with other angels such as Gabriel or saints. Some depictions with Gabriel date back to the 8th century, e.g. the stone casket at Notre Dame de Mortain church in France. He is very often present in scenes of the Last Judgement, but few other specific scenes, so most images including him are devotional rather than narrative. The angel who rescues Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego from the "fiery furnace" in the Book of Daniel Chapter 3 is usually regarded in Christian tradition as Michael; this is sometimes represented in Early Christian art and Eastern Orthodox icons, but rarely in later art of the Western church.

The Saint-Thégonnec Parish close is located at Saint-Thégonnec in the arrondissement of Morlaix in Brittany in north-western France. The enclos paroissial comprises the parish church of Notre-Dame, a triumphal arch and enclosure wall, an ossuary and the famous calvary. It is a listed historical monument. There is a second calvary set into the enclosure wall and the war memorial dedicated to those lost in the 1914-1918 war is also set into another section of the wall.

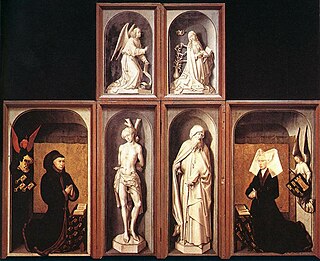

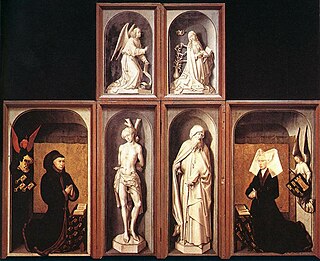

A winged altarpiece or winged retable is a special form of altarpiece, common in Northern and Central Europe, in which the central image, either a painting or relief sculpture can be hidden by hinged wings. It is called a triptych if there are two wings, a pentaptych if there are four, or a polyptych if there are four or more. The technical terms are derived from Ancient Greek: τρίς: trís or "triple"; πέντε: pénte or "five"; πολύς: polýs or "many"; and πτυχή: ptychē or "fold, layer".

The enclos paroissial or Parish close of Locronan comprises the parish church with adjoining chapel and a calvary. The article will also cover the nearby chapelle Notre-Dame-de-Bonne-Nouvelle. Locronan is a member of the Les Plus Beaux Villages de France association. The village's name means the "hermitage of Ronan", from the Breton lok which means hermitage, and after the founder Saint Ronan. It has previously been known as Saint-René-du-Bois. Saint Ronan is greatly venerated in Brittany. He was an Irish Christian missionary of the 6th century who came to the region to teach Christianity. As a consequence of Saint Ronan's close association with Locronan some of his relics are kept in the parish church. Locronan is located in the Châteaulin arrondissement of Finistère.