A central bank, reserve bank, or monetary authority is an institution that manages the currency, money supply, and interest rates of a state or formal monetary union, and oversees their commercial banking system. In contrast to a commercial bank, a central bank possesses a monopoly on increasing the monetary base in a financial crisis. Most central banks also have supervisory and regulatory powers to ensure the stability of member institutions, to prevent bank runs, and to discourage reckless or fraudulent behavior by member banks.

The Federal Reserve System is the central banking system of the United States of America. It was created on December 23, 1913, with the enactment of the Federal Reserve Act, after a series of financial panics led to the desire for central control of the monetary system in order to alleviate financial crises. Over the years, events such as the Great Depression in the 1930s and the Great Recession during the 2000s have led to the expansion of the roles and responsibilities of the Federal Reserve System.

Monetary policy concerns the actions of a central bank or other regulatory authorities that determine the size and rate of growth of the money supply. For example, in the United States, the Federal Reserve is in charge of monetary policy, and implements it primarily by performing operations that influence short-term interest rates.

The money supply is the total value of money available in an economy at a point of time. There are several ways to define "money", but standard measures usually include currency in circulation and demand deposits. The central bank of each country may use a definition of what constitutes money for its purposes.

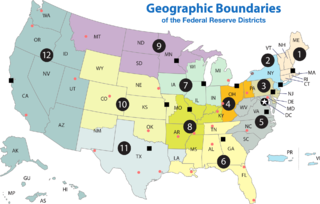

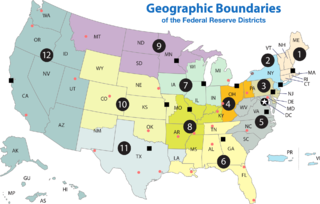

A Federal Reserve Bank is a regional bank of the Federal Reserve System, the central banking system of the United States. There are twelve in total, one for each of the twelve Federal Reserve Districts that were created by the Federal Reserve Act of 1913. The banks are jointly responsible for implementing the monetary policy set forth by the Federal Open Market Committee, and are divided as follows:

Federal Reserve Notes, also United States banknotes, are the banknotes currently used in the United States of America. Denominated in United States dollars, Federal Reserve Notes are printed by the United States Bureau of Engraving and Printing on paper made by Crane & Co. of Dalton, Massachusetts. Federal Reserve Notes are the only type of U.S. banknote currently produced. Federal Reserve Notes are authorized by Section 16 of the Federal Reserve Act of 1913 and are issued to the Federal Reserve Banks at the discretion of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The notes are then put into circulation by the Federal Reserve Banks, at which point they become liabilities of the Federal Reserve Banks and obligations of the United States.

Fractional-reserve banking is the most common form of banking practised by commercial banks worldwide. It involves banks accepting deposits from customers and making loans to borrowers, while holding in reserve an amount equal to only a fraction of the bank's deposit liabilities. Bank reserves are held as cash in the bank or as balances in the bank's account at the central bank. The minimum amount that banks are required to hold in liquid assets is determined by the country's central bank, and is called the reserve requirement or reserve ratio. Banks usually hold more than this minimum amount, keeping excess reserves.

Full-reserve banking is a proposed alternative to fractional-reserve banking in which banks would be required to keep the full amount of each depositor's funds in cash, ready for immediate withdrawal on demand. Funds deposited by customers in demand deposit accounts would not be loaned out by the bank because it would be legally required to retain the full deposit to satisfy potential demand for payments. Proposals for such systems generally do not place such restrictions on deposits that are not payable on demand, for example time deposits.

An open market operation (OMO) is an activity by a central bank to give liquidity in its currency to a bank or a group of banks. The central bank can either buy or sell government bonds in the open market or, in what is now mostly the preferred solution, enter into a repo or secured lending transaction with a commercial bank: the central bank gives the money as a deposit for a defined period and synchronously takes an eligible asset as collateral. A central bank uses OMO as the primary means of implementing monetary policy. The usual aim of open market operations is—aside from supplying commercial banks with liquidity and sometimes taking surplus liquidity from commercial banks—to manipulate the short-term interest rate and the supply of base money in an economy, and thus indirectly control the total money supply, in effect expanding money or contracting the money supply. This involves meeting the demand of base money at the target interest rate by buying and selling government securities, or other financial instruments. Monetary targets, such as inflation, interest rates, or exchange rates, are used to guide this implementation.

Foreign exchange reserves are cash and other reserve assets held by a central bank or other monetary authority that are primarily available to balance payments of the country, influence the foreign exchange rate of its currency, and to maintain confidence in financial markets. Reserves are held in one or more reserve currencies, nowadays mostly the United States dollar and to a lesser extent the euro.

Money creation, or money issuance, is the process by which the money supply of a country, or of an economic or monetary region, is increased. In most modern economies, most of the money supply is in the form of bank deposits. Central banks monitor the amount of money in the economy by measuring the so-called monetary aggregates.

Excess reserves are bank reserves held by a bank in excess of a reserve requirement for it set by a central bank.

The Independent Treasury was the system for managing the money supply of the United States federal government through the U.S. Treasury and its sub-treasuries, independently of the national banking and financial systems. It was created on August 6, 1846 by the 29th Congress, with the enactment of the Independent Treasury Act of 1846, and it functioned until the early 20th century, when the Federal Reserve System replaced it. During this time, the Treasury took over an ever-larger number of functions of a central bank and the U.S. Treasury Department came to be the major force in the U.S. money market.

Quantitative easing (QE) is a monetary policy whereby a central bank buys government bonds or other financial assets in order to inject money into the economy to expand economic activity. An unconventional form of monetary policy, it is usually used when inflation is very low or negative, and standard expansionary monetary policy has become ineffective. A central bank implements quantitative easing by buying financial assets from commercial banks and other financial institutions, thus raising the prices of those financial assets and lowering their yield, while simultaneously increasing the money supply. This differs from the more usual policy of buying or selling short-term government bonds to keep interbank interest rates at a specified target value.

Flow of funds accounts are a system of interrelated balance sheets for a nation, calculated periodically. There are two types of balance sheets: those showing

The United States dollar is the official currency of the United States and its territories per the Coinage Act of 1792. One dollar is divided into 100 cents, or into 1000 mills for accounting and taxing purposes. The Coinage Act of 1792 created a decimal currency by creating the dime, nickel, and penny coins, as well as the dollar, half dollar, and quarter dollar coins, all of which are still minted in 2020.

The U.S. central banking system, the Federal Reserve, in partnership with central banks around the world, took several steps to address the subprime mortgage crisis. Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke stated in early 2008: "Broadly, the Federal Reserve’s response has followed two tracks: efforts to support market liquidity and functioning and the pursuit of our macroeconomic objectives through monetary policy." A 2011 study by the Government Accountability Office found that "on numerous occasions in 2008 and 2009, the Federal Reserve Board invoked emergency authority under the Federal Reserve Act of 1913 to authorize new broad-based programs and financial assistance to individual institutions to stabilize financial markets. Loans outstanding for the emergency programs peaked at more than $1 trillion in late 2008."

The Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008, often called the "bank bailout of 2008," was proposed by Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson, passed by the 110th United States Congress, and signed into law by President George W. Bush. The act became law as part of Public Law 110-343 on October 3, 2008, in the midst of the financial crisis of 2007–08. The law created the $700 billion Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) to purchase toxic assets from banks. The funds for purchase of distressed assets were mostly redirected to inject capital into banks and other financial institutions while the Treasury continued to examine the usefulness of targeted asset purchases.

The interbank lending market is a market in which banks lend funds to one another for a specified term. Most interbank loans are for maturities of one week or less, the majority being overnight. Such loans are made at the interbank rate. A sharp decline in transaction volume in this market was a major contributing factor to the collapse of several financial institutions during the financial crisis of 2007–2008.

The trillion-dollar coin is a concept that emerged during the United States debt-ceiling crisis in 2011, as a proposed way to bypass any necessity for the United States Congress to raise the country's borrowing limit, through the minting of very high-value platinum coins. The concept gained more mainstream attention by late 2012 during the debates over the United States fiscal cliff negotiations and renewed debt-ceiling discussions. After reaching the headlines during the week of January 7, 2013, use of the trillion dollar coin concept was ultimately rejected by the Federal Reserve and the Treasury..