The Federal Reserve System is the central banking system of the United States. It was created on December 23, 1913, with the enactment of the Federal Reserve Act, after a series of financial panics led to the desire for central control of the monetary system in order to alleviate financial crises. Over the years, events such as the Great Depression in the 1930s and the Great Recession during the 2000s have led to the expansion of the roles and responsibilities of the Federal Reserve System.

The monetary policy of The United States is the set of policies which the Federal Reserve follows to achieve its twin objectives of high employment and stable inflation.

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) is a committee within the Federal Reserve System that is charged under United States law with overseeing the nation's open market operations. This Federal Reserve committee makes key decisions about interest rates and the growth of the United States money supply. Under the terms of the original Federal Reserve Act, each of the Federal Reserve banks was authorized to buy and sell in the open market bonds and short term obligations of the United States Government, bank acceptances, cable transfers, and bills of exchange. Hence, the reserve banks were at times bidding against each other in the open market. In 1922, an informal committee was established to execute purchases and sales. The Banking Act of 1933 formed an official FOMC.

George William Miller was an American businessman and investment banker who served as the 65th United States secretary of the treasury from 1979 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party, he also served as the 11th chairman of the Federal Reserve from 1978 to 1979. Miller was the first person to hold both of those posts.

William McChesney Martin Jr. was an American business executive who served as the 9th chairman of the Federal Reserve from 1951 to 1970, making him the longest holder of that position. He was nominated to the post by President Harry S. Truman and reappointed by four of his successors. Martin, who once considered becoming a Presbyterian minister, was described by a Washington journalist as "the happy Puritan".

In macroeconomics, an open market operation (OMO) is an activity by a central bank to give liquidity in its currency to a bank or a group of banks. The central bank can either buy or sell government bonds in the open market or, in what is now mostly the preferred solution, enter into a repo or secured lending transaction with a commercial bank: the central bank gives the money as a deposit for a defined period and synchronously takes an eligible asset as collateral.

The Federal Reserve System has faced various criticisms since it was authorized in 1913. Nobel laureate economist Milton Friedman and his fellow monetarist Anna Schwartz criticized the Fed's response to the Wall Street Crash of 1929 arguing that it greatly exacerbated the Great Depression. More recent prominent critics include former Congressman Ron Paul.

The discount window is an instrument of monetary policy that allows eligible institutions to borrow money from the central bank, usually on a short-term basis, to meet temporary shortages of liquidity caused by internal or external disruptions.

Excess reserves are bank reserves held by a bank in excess of a reserve requirement for it set by a central bank.

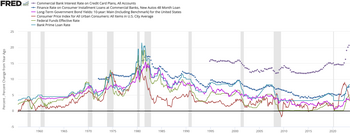

Bank rate, also known as discount rate in American English, is the rate of interest which a central bank charges on its loans and advances to a commercial bank. The bank rate is known by a number of different terms depending on the country, and has changed over time in some countries as the mechanisms used to manage the rate have changed.

Jeffrey M. Lacker is an American economist and was president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond until April 4, 2017. He is now a Distinguished Professor in the Department of Economics at the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Business in Richmond, Virginia.

Quantitative easing (QE) is a monetary policy action where a central bank purchases predetermined amounts of government bonds or other financial assets in order to stimulate economic activity. Quantitative easing is a novel form of monetary policy that came into wide application after the financial crisis of 2007–2008. It is used to mitigate an economic recession when inflation is very low or negative, making standard monetary policy ineffective. Quantitative tightening (QT) does the opposite, where for monetary policy reasons, a central bank sells off some portion of its holdings of government bonds or other financial assets.

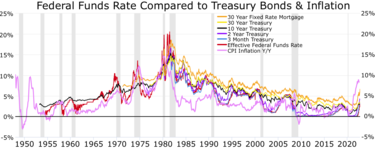

This is a list of historical rate actions by the United States Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). The FOMC controls the supply of credit to banks and the sale of treasury securities. The Federal Open Market Committee meets every two months during the fiscal year. At scheduled meetings, the FOMC meets and makes any changes it sees as necessary, notably to the federal funds rate and the discount rate. The committee may also take actions with a less firm target, such as an increasing liquidity by the sale of a set amount of Treasury bonds, or affecting the price of currencies both foreign and domestic by selling dollar reserves. Jerome Powell is the current chairperson of the Federal Reserve and the FOMC.

James Brian Bullard is the former chief executive officer and 12th president of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, a position he held from 2008 until August 14, 2023. In July 2023, he was named dean of the Mitchell E. Daniels Jr. School of Business at Purdue University.

The U.S. central banking system, the Federal Reserve, in partnership with central banks around the world, took several steps to address the subprime mortgage crisis. Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke stated in early 2008: "Broadly, the Federal Reserve’s response has followed two tracks: efforts to support market liquidity and functioning and the pursuit of our macroeconomic objectives through monetary policy." A 2011 study by the Government Accountability Office found that "on numerous occasions in 2008 and 2009, the Federal Reserve Board invoked emergency authority under the Federal Reserve Act of 1913 to authorize new broad-based programs and financial assistance to individual institutions to stabilize financial markets. Loans outstanding for the emergency programs peaked at more than $1 trillion in late 2008."

The interbank lending market is a market in which banks lend funds to one another for a specified term. Most interbank loans are for maturities of one week or less, the majority being overnight. Such loans are made at the interbank rate. A sharp decline in transaction volume in this market was a major contributing factor to the collapse of several financial institutions during the financial crisis of 2007–2008.

In monetary policy of the United States, the term Fedspeak is what Alan Blinder called "a turgid dialect of English" used by Federal Reserve Board chairs in making wordy, vague, and ambiguous statements. The strategy, which was used most prominently by Alan Greenspan, was used to prevent financial markets from overreacting to the chairman's remarks. The coinage is an intentional parallel to Newspeak.

Marvin Seth Goodfriend was an American economist. He held the Allan H. Meltzer Professorship in economics at Carnegie Mellon University; he was previously the director of research at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. Following his 2017 nomination to the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, the White House decided to forgo renominating Goodfriend at the beginning of the new term.

On September 17, 2019, interest rates on overnight repurchase agreements, which are short-term loans between financial institutions, experienced a sudden and unexpected spike. A measure of the interest rate on overnight repos in the United States, the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR), increased from 2.43 percent on September 16 to 5.25 percent on September 17. During the trading day, interest rates reached as high as 10 percent. The activity also affected the interest rates on unsecured loans between financial institutions, and the Effective Federal Funds Rate (EFFR), which serves as a measure for such interest rates, moved above its target range determined by the Federal Reserve.