The Commonwealth Games is a quadrennial international multi-sport event among athletes from the Commonwealth of Nations, which mostly consists of territories of the former British Empire. The event was first held in 1930 and, with the exception of 1942 and 1946, has successively run every four years since. The event was called the British Empire Games from 1930 to 1950, the British Empire and Commonwealth Games from 1954 to 1966, and British Commonwealth Games from 1970 to 1974. Athletes with a disability are included as full members of their national teams since 2002, making the Commonwealth Games the first fully inclusive international multi-sport event. In 2018, the Games became the first global multi-sport event to feature an equal number of men's and women's medal events, and four years later they became the first global multi-sport event to have more events for women than men.

The Crystal Palace was a cast iron and plate glass structure, originally built in Hyde Park, London, to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. The exhibition took place from 1 May to 15 October 1851, and more than 14,000 exhibitors from around the world gathered in its 990,000 square feet (92,000 m2) exhibition space to display examples of technology developed in the Industrial Revolution. Designed by Joseph Paxton, the Great Exhibition building was 1,851 feet (564 m) long, with an interior height of 128 feet (39 m), and was three times the size of St Paul's Cathedral.

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, also known as the Great Exhibition or the Crystal Palace Exhibition, was an international exhibition that took place in Hyde Park, London, from 1 May to 15 October 1851. It was the first in a series of World's Fairs, exhibitions of culture and industry that became popular in the 19th century. The event was organised by Henry Cole and Prince Albert, husband of Victoria, Queen of the United Kingdom.

The National Sports Centre at Crystal Palace in south London, England is a large sports centre and outdoor athletics stadium. It was opened in 1964 in Crystal Palace Park, close to the site of the former Crystal Palace Exhibition building which had been destroyed by fire in 1936, and is on the same site as the former FA Cup Final venue which was used here between 1895 and 1914.

The Dominion of New Zealand was the historical successor to the Colony of New Zealand. It was a constitutional monarchy with a high level of self-government within the British Empire.

The Franco-British Exhibition was a large public fair held in London between 14 May and 31 October 1908. It was the first in the series of the White City Exhibitions. The exhibition attracted 8 million visitors and celebrated the Entente Cordiale signed in 1904 by the United Kingdom and France. The chief architect of the buildings was John Belcher.

The 1873 Vienna World's Fair was the large world exposition that was held from 1 May to 31 October 1873 in the Austria-Hungarian capital Vienna. Its motto was "Culture and Education".

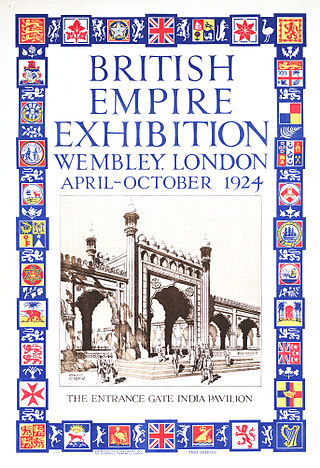

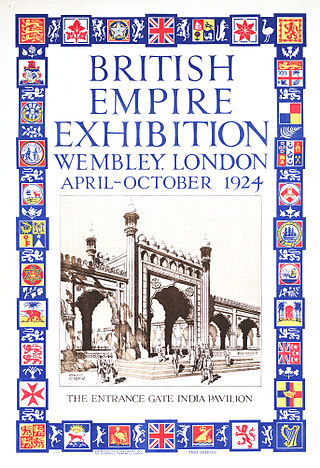

The British Empire Exhibition was a colonial exhibition held at Wembley Park, London England from 23 April to 1 November 1924 and from 9 May to 31 October 1925.

The Golden Jubilee of Elizabeth II was the international celebration held in 2002 marking the 50th anniversary of the accession of Queen Elizabeth II on 6 February 1952. It was intended by the Queen to be both a commemoration of her 50 years as monarch and an opportunity for her to officially and personally thank her people for their loyalty.

The Empire Exhibition was an international Exhibition held at Bellahouston Park in Glasgow, Scotland, from May to December 1938.

The Pageant of Empire was the name given to various historical pageants celebrating the British Empire which were held in Britain during the early twentieth century. For example, there was a small Pageant of Empire at the town of Builth Wells in 1909. In 1911 a giant Pageant of Empire took place at the Festival of Empire at the Crystal Palace in Sydenham, where thousands of amateur performers acted out historical scenes. The most notable was the Pageant of Empire which took place in London in 1924.

At the 1930 British Empire Games, the athletics events were held at the Civic Stadium in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. The programme featured 21 men's events, with all measurements being done in imperial units.

A dominion was any of several largely self-governing countries of the British Empire. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of colonial self-governance increased unevenly over the late 19th century through the 1930s, and some vestiges of empire lasted in some areas into the late 20th century. With the evolution of the British Empire into the Commonwealth of Nations, finalised in 1949, the dominions became independent states, either as commonwealth republics or commonwealth realms.

The International Exhibition of Science, Art and Industry was the first of 4 international exhibitions held in Glasgow, Scotland during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It took place at Kelvingrove Park between May and November 1888. The main aim of the exhibition was to draw international attention to the city's achievements in applied sciences, industry and the arts during the Industrial Revolution. However, it was also hoped the Exhibition would raise enough money for a much-needed museum, art gallery and school of art in the city. The exhibition was opened by the Prince of Wales, as honorary president of the exhibition, on 8 May 1888. It was the greatest exhibition held outside London and the largest ever in Scotland during the 19th century.

Thomas Edward Donne (1860–1945) was a New Zealand civil servant, author, recreational hunter and collector of Māori antiquities and New Zealand fine art.

The Scottish Exhibition of National History, Art and Industry was held in Glasgow in 1911. It was the third of 4 international exhibitions held in Glasgow, Scotland during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Bristol International Exhibition was held on Ashton Meadows in the Bower Ashton area of Bristol, England in 1914. The exhibition which had been planned since 1912 was a commercial venture and not fully supported by the civic dignitaries of the city which caused difficulties raising the funds needed. Most of the construction of the venues was from wooden frames covered by plasterboard and occurred in just 2 months prior to opening. It opened on 28 May 1914 was closed on 6 June. Further funding was raised and the exhibition reopened, but continued to struggle with lower than expected attendance and, following several court hearings, finally closed on 15 August just after the outbreak of World War I.

Philip Francis Sharpley was a New Zealand track and field athlete who represented his country at the 1938 British Empire Games.

The 1895 African Exhibition at The Crystal Palace was an instance of a human zoo in London. The colonial exhibition presented around eighty people brought from Somalia along with two-hundred African animals.

The 1905 Colonial and Indian Exhibition took place at the Crystal Palace in London and is reported to have been larger and more popular than the 1895 African Exhibition and the most direct forerunner of the 1911 Festival of Empire, two other colonial events that took place at the same site.