Related Research Articles

Nutrition is the biochemical and physiological process by which an organism uses food to support its life. It provides organisms with nutrients, which can be metabolized to create energy and chemical structures. Failure to obtain sufficient nutrients causes malnutrition. Nutritional science is the study of nutrition, though it typically emphasizes human nutrition.

A nutrient is a substance used by an organism to survive, grow, and reproduce. The requirement for dietary nutrient intake applies to animals, plants, fungi, and protists. Nutrients can be incorporated into cells for metabolic purposes or excreted by cells to create non-cellular structures, such as hair, scales, feathers, or exoskeletons. Some nutrients can be metabolically converted to smaller molecules in the process of releasing energy, such as for carbohydrates, lipids, proteins, and fermentation products, leading to end-products of water and carbon dioxide. All organisms require water. Essential nutrients for animals are the energy sources, some of the amino acids that are combined to create proteins, a subset of fatty acids, vitamins and certain minerals. Plants require more diverse minerals absorbed through roots, plus carbon dioxide and oxygen absorbed through leaves. Fungi live on dead or living organic matter and meet nutrient needs from their host.

Human nutrition deals with the provision of essential nutrients in food that are necessary to support human life and good health. Poor nutrition is a chronic problem often linked to poverty, food security, or a poor understanding of nutritional requirements. Malnutrition and its consequences are large contributors to deaths, physical deformities, and disabilities worldwide. Good nutrition is necessary for children to grow physically and mentally, and for normal human biological development.

A healthy diet is a diet that maintains or improves overall health. A healthy diet provides the body with essential nutrition: fluid, macronutrients such as protein, micronutrients such as vitamins, and adequate fibre and food energy.

Nutrition and pregnancy refers to the nutrient intake, and dietary planning that is undertaken before, during and after pregnancy. Nutrition of the fetus begins at conception. For this reason, the nutrition of the mother is important from before conception as well as throughout pregnancy and breastfeeding. An ever-increasing number of studies have shown that the nutrition of the mother will have an effect on the child, up to and including the risk for cancer, cardiovascular disease, hypertension and diabetes throughout life.

Stunted growth, also known as stunting or linear growth failure, is defined as impaired growth and development manifested by low height-for-age. It is a primary manifestation of malnutrition and recurrent infections, such as diarrhea and helminthiasis, in early childhood and even before birth, due to malnutrition during fetal development brought on by a malnourished mother. The definition of stunting according to the World Health Organization (WHO) is for the "height-for-age" value to be less than two standard deviations of the median of WHO Child Growth Standards. Stunted growth is usually associated with poverty, unsanitary environmental conditions, maternal undernutrition, frequent illness, and/or inappropriate feeding practice and care during early years of life.

Micronutrient deficiency is defined as the sustained insufficient supply of vitamins and minerals needed for growth and development, as well as to maintain optimal health. Since some of these compounds are considered essentials, micronutrient deficiencies are often the result of an inadequate intake. However, it can also be associated to poor intestinal absorption, presence of certain chronic illnesses and elevated requirements.

Vitamin D deficiency or hypovitaminosis D is a vitamin D level that is below normal. It most commonly occurs in people when they have inadequate exposure to sunlight, particularly sunlight with adequate ultraviolet B rays (UVB). Vitamin D deficiency can also be caused by inadequate nutritional intake of vitamin D; disorders that limit vitamin D absorption; and disorders that impair the conversion of vitamin D to active metabolites, including certain liver, kidney, and hereditary disorders. Deficiency impairs bone mineralization, leading to bone-softening diseases, such as rickets in children. It can also worsen osteomalacia and osteoporosis in adults, increasing the risk of bone fractures. Muscle weakness is also a common symptom of vitamin D deficiency, further increasing the risk of fall and bone fractures in adults. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with the development of schizophrenia.

Prenatal nutrition addresses nutrient recommendations before and during pregnancy. Nutrition and weight management before and during pregnancy has a profound effect on the development of infants. This is a rather critical time for healthy development since infants rely heavily on maternal stores and nutrient for optimal growth and health outcome later in life.

Relatively speaking, the brain consumes an immense amount of energy in comparison to the rest of the body. The mechanisms involved in the transfer of energy from foods to neurons are likely to be fundamental to the control of brain function. Human bodily processes, including the brain, all require both macronutrients, as well as micronutrients.

Developmental Origins of Health and Disease is an approach to medical research factors that can lead to the development of human diseases during early life development. These factors include the role of prenatal and perinatal exposure to environmental factors, such as undernutrition, stress, environmental chemical, etc. This approach includes an emphasis on epigenetic causes of adult chronic non-communicable diseases. As well as physical human disease, the psychopathology of the foetus can also be predicted by epigenetic factors.

Nutrition psychology (NP) is the psychological study of the relationship between dietary intake and different aspects of psychological health. It is an applied field that uses an interdisciplinary approach to examine the influence of diet on mental health. Nutrition psychology seeks to understand the relationship between nutritional behavior and mental health/well-being NP is a sub-field of psychology and more specifically of health psychology. It may be applied to numerous different fields including: psychology, dietetics, nutrition, and marketing. NP is a fairly new field with a brief history that has already started to contribute information and knowledge to psychology. There are two main areas of controversy within nutrition psychology. The first area of controversy is that the topic can be viewed in two different ways. It can be viewed as nutrition affecting psychological functions, or psychological choices and behavior influencing nutrition and health. The second controversy is the defining of what is "healthy" or "normal" as related to nutrition.

Infant feeding is the practice of feeding infants. Breast milk provides the best nutrition when compared to infant formula. Infants are usually introduced to solid foods at around four to six months of age.

Environmental enteropathy is an acquired small intestinal disorder characterized by gut inflammation, reduced absorptive surface area in small intestine, and disruption of intestinal barrier function. EE is most common amongst children living in low-resource settings. Acute symptoms are typically minimal or absent. EE can lead to malnutrition, anemia, stunted growth, impaired brain development, and impaired response to oral vaccinations.

Undernutrition in children, occurs when children do not consume enough calories, protein, or micronutrients to maintain good health. It is common globally and may result in both short and long term irreversible adverse health outcomes. Undernutrition is sometimes used synonymously with malnutrition, however, malnutrition could mean both undernutrition or overnutrition. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that malnutrition accounts for 54 percent of child mortality worldwide, which is about 1 million children. Another estimate, also by WHO, states that childhood underweight is the cause for about 35% of all deaths of children under the age of five worldwide.

As in the human practice of veganism, vegan dog foods are those formulated with the exclusion of ingredients that contain or were processed with any part of an animal, or any animal byproduct. Vegan dog food may incorporate the use of fruits, vegetables, cereals, legumes including soya, nuts, vegetable oils, as well as any other non-animal based foods.

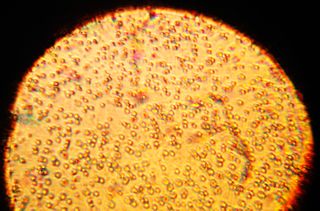

The human milk microbiota, also known as human milk probiotics (HMP), refers to the microbiota (community of microorganisms) residing in the human mammary glands and breast milk. Human breast milk has been traditionally assumed to be sterile, but more recently both microbial culture and culture-independent techniques have confirmed that human milk contains diverse communities of bacteria which are distinct from other microbial communities inhabiting the human body.

Nutritional immunology is a field of immunology that focuses on studying the influence of nutrition on the immune system and its protective functions. Part of nutritional immunology involves studying the possible effects of diet on the prevention and management on developing autoimmune diseases, chronic diseases, allergy, cancer and infectious diseases. Other related topics of nutritional immunology are: malnutrition, malabsorption and nutritional metabolic disorders including the determination of their immune products.

Child development in India is the Indian experience of biological, psychological, and emotional changes which children experience as they grow into adults. Child development has a significant influence on personal health and, at a national level, the health of people in India.

Nutritional epigenetics is a science that studies the effects of nutrition on gene expression and chromatin accessibility. It is a subcategory of nutritional genomics that focuses on the effects of bioactive food components on epigenetic events.

References

- 1 2 Linnér A, Almgren M (2020). "Epigenetic programming-The important first 1000 days". Acta Paediatrica. 109 (3): 443–452. doi:10.1111/apa.15050. PMID 31603247. S2CID 204242659.

- ↑ Brines, Juan; Rigourd, Virginie; Billeaud, Claude (2022). "The First 1000 Days of Infant". Healthcare. 10 (1): 106. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10010106 . ISSN 2227-9032. PMC 8775982 . PMID 35052270.

- 1 2 3 Beluska-Turkan, Katrina; Korczak, Renee; Hartell, Beth; Moskal, Kristin; Maukonen, Johanna; Alexander, Diane E.; Salem, Norman; Harkness, Laura; Ayad, Wafaa; Szaro, Jacalyn; Zhang, Kelly; Siriwardhana, Nalin (2019). "Nutritional Gaps and Supplementation in the First 1000 Days". Nutrients. 11 (12): 2891. doi: 10.3390/nu11122891 . ISSN 2072-6643. PMC 6949907 . PMID 31783636.

- ↑ Mameli C, Mazzantini S, Zuccotti GV (2016). "Nutrition in the First 1000 Days: The Origin of Childhood Obesity". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 13 (9): 838. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13090838 . PMC 5036671 . PMID 27563917.

- ↑ Blake-Lamb TL, Locks LM, Perkins ME, Woo Baidal JA, Cheng ER, Taveras EM (2016). "Interventions for Childhood Obesity in the First 1,000 Days A Systematic Review". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 50 (6): 780–789. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.11.010. PMC 5207495 . PMID 26916260.

- ↑ Woo Baidal JA, Locks LM, Cheng ER, Blake-Lamb TL, Perkins ME, Taveras EM (2016). "Risk Factors for Childhood Obesity in the First 1,000 Days: A Systematic Review". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 50 (6): 761–779. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.11.012. PMID 26916261.

- ↑ Georgiadis A, Penny ME (2017). "Child undernutrition: opportunities beyond the first 1000 days". The Lancet. Public Health. 2 (9): e399. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30154-8 . PMID 29253410.

- ↑ Scott, Jane A. (2020). "The first 1000 days: A critical period of nutritional opportunity and vulnerability". Nutrition & Dietetics. 77 (3): 295–297. doi: 10.1111/1747-0080.12617 . ISSN 1446-6368. PMID 32478460. S2CID 219168825.

- 1 2 3 Robertson RC, Manges AR, Finlay BB, Prendergast AJ (2019). "The Human Microbiome and Child Growth - First 1000 Days and Beyond". Trends in Microbiology. 27 (2): 131–147. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2018.09.008 . PMID 30529020. S2CID 54479497.

- ↑ Billeaud C, Brines J, Belcadi W, Castel B, Rigourd V (2021). "Nutrition of Pregnant and Lactating Women in the First 1000 Days of Infant". Healthcare. 10 (1): 65. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10010065 . PMC 8775626 . PMID 35052229.

- ↑ Aires J (2021). "First 1000 Days of Life: Consequences of Antibiotics on Gut Microbiota". Frontiers in Microbiology. 12: 681427. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.681427 . PMC 8170024 . PMID 34093505.

- ↑ Cukrowska B, Bierła JB, Zakrzewska M, Klukowski M, Maciorkowska E (2020). "The Relationship between the Infant Gut Microbiota and Allergy. The Role of Bifidobacterium breve and Prebiotic Oligosaccharides in the Activation of Anti-Allergic Mechanisms in Early Life". Nutrients. 12 (4): 946. doi: 10.3390/nu12040946 . PMC 7230322 . PMID 32235348.

- 1 2 Esch, Betty C. A. M. van; Porbahaie, Mojtaba; Abbring, Suzanne; Garssen, Johan; Potaczek, Daniel P.; Savelkoul, Huub F. J.; Neerven, R. J. Joost van (2020). "The Impact of Milk and Its Components on Epigenetic Programming of Immune Function in Early Life and Beyond: Implications for Allergy and Asthma". Frontiers in Immunology. 11: 2141. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.02141 . ISSN 1664-3224. PMC 7641638 . PMID 33193294.

- ↑ Bianco-Miotto, T.; Craig, J. M.; Gasser, Y. P.; Dijk, S. J. van; Ozanne, S. E. (2017). "Epigenetics and DOHaD: from basics to birth and beyond". Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease. 8 (5): 513–519. doi:10.1017/S2040174417000733. ISSN 2040-1744. PMID 28889823. S2CID 10545857.

- ↑ Block, Tomasz; El-Osta, Assam (2017). "Epigenetic programming, early life nutrition and the risk of metabolic disease". Atherosclerosis. 266: 31–40. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2017.09.003. ISSN 0021-9150. PMID 28950165.

- ↑ Ong, Thomas P.; Ozanne, Susan E. (2015). "Developmental programming of type 2 diabetes: early nutrition and epigenetic mechanisms". Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care. 18 (4): 354–360. doi:10.1097/MCO.0000000000000177. ISSN 1363-1950. PMID 26049632. S2CID 1682293.

- 1 2 Babenko O, Kovalchuk I, Metz GA (2015). "Stress-induced perinatal and transgenerational epigenetic programming of brain development and mental health". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 48: 70–91. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.11.013. PMID 25464029. S2CID 24803183.

- ↑ Joubert BR, Felix JF, Yousefi P, Bakulski KM, Just AC, Breton C, et al. (2016). "DNA Methylation in Newborns and Maternal Smoking in Pregnancy: Genome-wide Consortium Meta-analysis". American Journal of Human Genetics. 98 (4): 680–696. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.02.019. PMC 4833289 . PMID 27040690.

- ↑ Provenzi L, Guida E, Montirosso R (2018). "Preterm behavioral epigenetics: A systematic review". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 84: 262–271. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.08.020. PMID 28867654. S2CID 22540646.

- ↑ Vaiserman AM (2015). "Epigenetic programming by early-life stress: Evidence from human populations". Developmental Dynamics. 244 (3): 254–265. doi:10.1002/dvdy.24211. PMID 25298004. S2CID 18557835.

- ↑ Likhar, Akanksha; Patil, Manoj S (2022-10-08). "Importance of Maternal Nutrition in the First 1,000 Days of Life and Its Effects on Child Development: A Narrative Review". Cureus. 14 (10): e30083. doi: 10.7759/cureus.30083 . ISSN 2168-8184. PMC 9640361 . PMID 36381799.

- ↑ Beluska-Turkan, Katrina; Korczak, Renee; Hartell, Beth; Moskal, Kristin; Maukonen, Johanna; Alexander, Diane E.; Salem, Norman; Harkness, Laura; Ayad, Wafaa; Szaro, Jacalyn; Zhang, Kelly; Siriwardhana, Nalin (2019-11-27). "Nutritional Gaps and Supplementation in the First 1000 Days". Nutrients. 11 (12): 2891. doi: 10.3390/nu11122891 . ISSN 2072-6643. PMC 6949907 . PMID 31783636.

- ↑ Bragg, Megan G; Prado, Elizabeth L; Stewart, Christine P (2022-03-10). "Choline and docosahexaenoic acid during the first 1000 days and children's health and development in low- and middle-income countries". Nutrition Reviews. 80 (4): 656–676. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuab050. ISSN 0029-6643. PMC 8907485 . PMID 34338760.

- ↑ Burke RM, Leon JS, Suchdev PS (2014). "Identification, prevention and treatment of iron deficiency during the first 1000 days". Nutrients. 6 (10): 4093–4114. doi: 10.3390/nu6104093 . PMC 4210909 . PMID 25310252.

- ↑ Velasco, Inés; Bath, Sarah; Rayman, Margaret (2018-03-01). "Iodine as Essential Nutrient during the First 1000 Days of Life". Nutrients. 10 (3): 290. doi: 10.3390/nu10030290 . ISSN 2072-6643. PMC 5872708 . PMID 29494508.

- ↑ Cusick, Sarah E.; Georgieff, Michael K. (August 2016). "The Role of Nutrition in Brain Development: The Golden Opportunity of the "First 1000 Days"". The Journal of Pediatrics. 175: 16–21. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.05.013. PMC 4981537 . PMID 27266965.

- ↑ Elmadfa I, Meyer AL (2012). "Vitamins for the first 1000 days: preparing for life". International Journal for Vitamin and Nutrition Research. 82 (5): 342–347. doi:10.1024/0300-9831/a000129. PMID 23798053. S2CID 6666227.

- ↑ Schwarzenberg SJ, Georgieff MK (2018). "Advocacy for Improving Nutrition in the First 1000 Days to Support Childhood Development and Adult Health". Pediatrics. 141 (2): e20173716. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3716 . PMID 29358479.

- ↑ Cusick SE, Georgieff MK (2016). "The Role of Nutrition in Brain Development: The Golden Opportunity of the "First 1000 Days"". The Journal of Pediatrics. 175: 16–21. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.05.013. PMC 4981537 . PMID 27266965.

- 1 2 Mameli, Chiara; Mazzantini, Sara; Zuccotti, Gian (2016). "Nutrition in the First 1000 Days: The Origin of Childhood Obesity". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 13 (9): 838. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13090838 . ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 5036671 . PMID 27563917.

- ↑ Thompson, Amanda L. (May 2012). "Developmental origins of obesity: Early feeding environments, infant growth, and the intestinal microbiome". American Journal of Human Biology. 24 (3): 350–360. doi:10.1002/ajhb.22254. PMID 22378322. S2CID 29748011.

- ↑ Mameli, Chiara; Mazzantini, Sara; Zuccotti, Gian (2016). "Nutrition in the First 1000 Days: The Origin of Childhood Obesity". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 13 (9): 838. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13090838 . ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 5036671 . PMID 27563917.

- ↑ Rughani, Ankur; Friedman, Jacob E.; Tryggestad, Jeanie B. (September 2020). "Type 2 Diabetes in Youth: the Role of Early Life Exposures". Current Diabetes Reports. 20 (9): 45. doi:10.1007/s11892-020-01328-6. ISSN 1534-4827. PMID 32767148. S2CID 221019597.