Ibn Sina, commonly known in the West as Avicenna, was a preeminent philosopher and physician of the Muslim world, flourishing during the Islamic Golden Age, serving in the courts of various Iranian rulers. He is often described as the father of early modern medicine. His philosophy was of the Muslim Peripatetic school derived from Aristotelianism.

In many religious and philosophical traditions, the soul is the non-material essence of a person, which includes one's identity, personality, and memories, an immaterial aspect or essence of a living being that is believed to be able to survive physical death. The concept of the soul is generally applied to humans, although it can also be applied to other living or even non-living entities, as in animism.

Ibn Rushd, often Latinized as Averroes, was an Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psychology, mathematics, Islamic jurisprudence and law, and linguistics. The author of more than 100 books and treatises, his philosophical works include numerous commentaries on Aristotle, for which he was known in the Western world as The Commentator and Father of Rationalism.

The Book of Healing is a scientific and philosophical encyclopedia written by Abu Ali ibn Sīna from medieval Persia, near Bukhara in Maverounnahr. He most likely began to compose the book in 1014, completed it around 1020, and published it in 1027.

Islamic philosophy is philosophy that emerges from the Islamic tradition. Two terms traditionally used in the Islamic world are sometimes translated as philosophy—falsafa, which refers to philosophy as well as logic, mathematics, and physics; and Kalam, which refers to a rationalist form of Scholastic Islamic theology which includes the schools of Maturidiyah, Ashaira and Mu'tazila.

Early Islamic philosophy or classical Islamic philosophy is a period of intense philosophical development beginning in the 2nd century AH of the Islamic calendar and lasting until the 6th century AH. The period is known as the Islamic Golden Age, and the achievements of this period had a crucial influence in the development of modern philosophy and science. For Renaissance Europe, "Muslim maritime, agricultural, and technological innovations, as well as much East Asian technology via the Muslim world, made their way to western Europe in one of the largest technology transfers in world history." This period starts with al-Kindi in the 9th century and ends with Averroes at the end of 12th century. The death of Averroes effectively marks the end of a particular discipline of Islamic philosophy usually called the Peripatetic Arabic School, and philosophical activity declined significantly in Western Islamic countries, namely in Islamic Spain and North Africa, though it persisted for much longer in the Eastern countries, in particular Persia and India where several schools of philosophy continued to flourish: Avicennism, Illuminationist philosophy, Mystical philosophy, and Transcendent theosophy.

Tawhid is the concept of monotheism in Islam. Tawhid is the religion's central and single most important concept, upon which a Muslim's entire religious adherence rests. It unequivocally holds that God is indivisibly one (ahad) and single (wahid).

Sensory deprivation or perceptual isolation is the deliberate reduction or removal of stimuli from one or more of the senses. Simple devices such as blindfolds or hoods and earmuffs can cut off sight and hearing, while more complex devices can also cut off the sense of smell, touch, taste, thermoception (heat-sense), and the ability to know which way is down. Sensory deprivation has been used in various alternative medicines and in psychological experiments. When deprived of sensation, the brain attempts to restore sensation in the form of hallucinations.

This article covers the conversations between Islamic philosophy and Jewish philosophy, and mutual influence on each other in response to questions and challenges brought into wide circulation through Aristotelianism, Neo-platonism, and the Kalam, focusing especially on the period from 800–1400 CE.

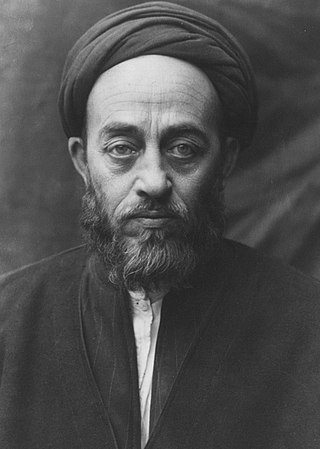

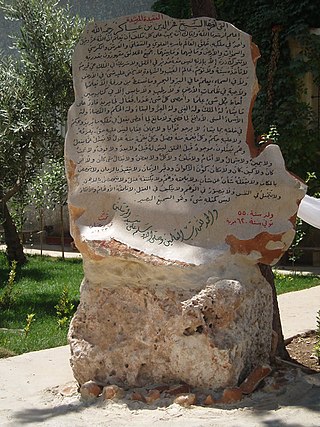

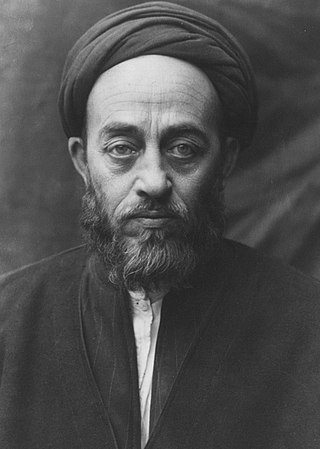

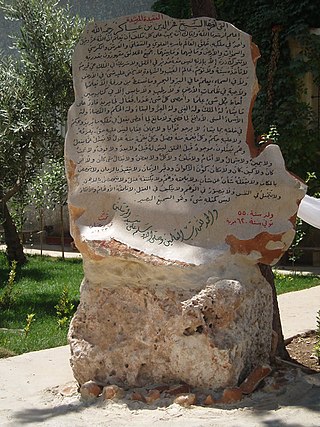

Muhammad Husayn Tabataba'i was an Iranian scholar, theorist, philosopher and one of the most prominent thinkers of modern Shia Islam. He is perhaps best known for his Tafsir al-Mizan, a twenty-seven-volume work of tafsir, which he produced between 1954 and 1972. He is commonly known as Allameh Tabataba'i and the Allameh Tabataba'i University in Tehran is named after him.

The Incoherence of the Philosophers is a landmark 11th-century work by the Muslim polymath al-Ghazali and a student of the Asharite school of Islamic theology criticizing the Avicennian school of early Islamic philosophy. Muslim philosophers such as Ibn Sina (Avicenna) and al-Farabi (Alpharabius) are denounced in this book, as they follow Greek philosophy even when, in the author's perception, it contradicts Islam. The text was dramatically successful, and marked a milestone in the ascendance of the Asharite school within Islamic philosophy and theological discourse.

Transcendent theosophy or al-hikmat al-muta’āliyah, the doctrine and philosophy developed by Persian philosopher Mulla Sadra, is one of two main disciplines of Islamic philosophy that are currently live and active.

Sufi philosophy includes the schools of thought unique to Sufism, the mystical tradition within Islam, also termed as Tasawwuf or Faqr according to its adherents. Sufism and its philosophical tradition may be associated with both Sunni and Shia branches of Islam. It has been suggested that Sufi thought emerged from the Middle East in the eighth century CE, but adherents are now found around the world.

Nikolay Onufriyevich Lossky, also known as N. O. Lossky, was a Russian philosopher, representative of Russian idealism, intuitionist epistemology, personalism, libertarianism, ethics and axiology. He gave his philosophical system the name intuitive-personalism. Born in Latvia, he spent his working life in St. Petersburg, New York, and Paris. He was the father of the influential Christian theologian Vladimir Lossky.

The philosophy of self examines the idea of the self at a conceptual level. Many different ideas on what constitutes self have been proposed, including the self being an activity, the self being independent of the senses, the bundle theory of the self, the self as a narrative center of gravity, and the self as a linguistic or social construct rather than a physical entity. The self is also an important concept in Eastern philosophy, including Buddhist philosophy.

An ontological argument is a philosophical argument, made from an ontological basis, that is advanced in support of the existence of God. Such arguments tend to refer to the state of being or existing. More specifically, ontological arguments are commonly conceived a priori in regard to the organization of the universe, whereby, if such organizational structure is true, God must exist.

Dawud Ibn Umar Al-Antaki also known as Dawud Al-Antaki was a blind Muslim physician and pharmacist active in Cairo. He was born during the XVI in Al-Foah and died around in Mecca in 1597. He lived most of his life in Antioch before made a pilgrimage to Mecca and took advantage of the trip to visited Damascus and Cairo. He will then settle in Mecca.

The Proof of the Truthful is a formal argument for proving the existence of God introduced by the Islamic philosopher Avicenna. Avicenna argued that there must be a "necessary existent", an entity that cannot not exist. The argument says that the entire set of contingent things must have a cause that is not contingent because otherwise it would be included in the set. Furthermore, through a series of arguments, he derived that the necessary existent must have attributes that he identified with God in Islam, including unity, simplicity, immateriality, intellect, power, generosity, and goodness.

The unity of the intellect, a philosophical theory proposed by the medieval Andalusian philosopher Averroes (1126–1198), asserted that all humans share the same intellect. Averroes expounded his theory in his long commentary on Aristotle's On the Soul to explain how universal knowledge is possible within the Aristotelian philosophy of mind. Averroes's theory was influenced by related ideas propounded by previous thinkers such as Aristotle himself, Plotinus, Al-Farabi, Avicenna and Avempace.

Al-Nijat min al-Qarq fi Bahr al-Zalalaat known as Al-Nijat is one of the most famous philosophical works of the Persian sage Avicenna. The general theme of the book is philosophy and includes topics in the fields of logic, physics, mathematics and theology.