Exercise is intentional physical activity to enhance or maintain fitness and overall health.

Kinesiology is the scientific study of human body movement. Kinesiology addresses physiological, anatomical, biomechanical, pathological, neuropsychological principles and mechanisms of movement. Applications of kinesiology to human health include biomechanics and orthopedics; strength and conditioning; sport psychology; motor control; skill acquisition and motor learning; methods of rehabilitation, such as physical and occupational therapy; and sport and exercise physiology. Studies of human and animal motion include measures from motion tracking systems, electrophysiology of muscle and brain activity, various methods for monitoring physiological function, and other behavioral and cognitive research techniques.

Delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) is the pain and stiffness felt in muscles after unaccustomed or strenuous exercise. The soreness is felt most strongly 24 to 72 hours after the exercise. It is thought to be caused by eccentric (lengthening) exercise, which causes small-scale damage (microtrauma) to the muscle fibers. After such exercise, the muscle adapts rapidly to prevent muscle damage, and thereby soreness, if the exercise is repeated.

Stretching is a form of physical exercise in which a specific muscle or tendon is deliberately expanded and flexed in order to improve the muscle's felt elasticity and achieve comfortable muscle tone. The result is a feeling of increased muscle control, flexibility, and range of motion. Stretching is also used therapeutically to alleviate cramps and to improve function in daily activities by increasing range of motion.

Sarcoplasm is the cytoplasm of a muscle cell. It is comparable to the cytoplasm of other cells, but it contains unusually large amounts of glycogen (a polymer of glucose), myoglobin, a red-colored protein necessary for binding oxygen molecules that diffuse into muscle fibers, and mitochondria. The calcium ion concentration in sarcoplasma is also a special element of the muscle fiber; it is the means by which muscle contractions take place and are regulated. The sarcoplasm plays a critical role in muscle contraction as an increase in Ca2+ concentration in the sarcoplasm begins the process of filament sliding. A decrease in Ca2+ in the sarcoplasm subsequently ceases filament sliding. The sarcoplasm also aids in pH and ion balance within muscle cells.

Cryotherapy, sometimes known as cold therapy, is the local or general use of low temperatures in medical therapy. Cryotherapy may be used to treat a variety of tissue lesions. The most prominent use of the term refers to the surgical treatment, specifically known as cryosurgery or cryoablation. Cryosurgery is the application of extremely low temperatures to destroy abnormal or diseased tissue and is used most commonly to treat skin conditions.

Strength training, also known as weight training or resistance training, involves the performance of physical exercises that are designed to improve strength and endurance. It is often associated with the lifting of weights. It can also incorporate a variety of training techniques such as bodyweight exercises, isometrics, and plyometrics.

High-intensity interval training (HIIT) is a training protocol alternating short periods of intense or explosive anaerobic exercise with brief recovery periods until the point of exhaustion. HIIT involves exercises performed in repeated quick bursts at maximum or near maximal effort with periods of rest or low activity between bouts. The very high level of intensity, the interval duration, and number of bouts distinguish it from aerobic (cardiovascular) activity, because the body significantly recruits anaerobic energy systems. The method thereby relies on "the anaerobic energy releasing system almost maximally".

Sarcopenia is a type of muscle loss that occurs with aging and/or immobility. It is characterized by the degenerative loss of skeletal muscle mass, quality, and strength. The rate of muscle loss is dependent on exercise level, co-morbidities, nutrition and other factors. The muscle loss is related to changes in muscle synthesis signalling pathways. It is distinct from cachexia, in which muscle is degraded through cytokine-mediated degradation, although the two conditions may co-exist. Sarcopenia is considered a component of frailty syndrome. Sarcopenia can lead to reduced quality of life, falls, fracture, and disability.

A negative repetition is the repetition of a technique in weight lifting in which the lifter performs the eccentric phase of a lift. Instead of pressing the weight up slowly, in proper form, a spotter generally aids in the concentric, or lifting, portion of the repetition while the lifter slowly performs the eccentric phase for 3–6 seconds.

Myofilaments are the three protein filaments of myofibrils in muscle cells. The main proteins involved are myosin, actin, and titin. Myosin and actin are the contractile proteins and titin is an elastic protein. The myofilaments act together in muscle contraction, and in order of size are a thick one of mostly myosin, a thin one of mostly actin, and a very thin one of mostly titin.

Electrical muscle stimulation (EMS), also known as neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) or electromyostimulation, is the elicitation of muscle contraction using electric impulses. EMS has received an increasing amount of attention in the last few years for many reasons: it can be utilized as a strength training tool for healthy subjects and athletes; it could be used as a rehabilitation and preventive tool for people who are partially or totally immobilized; it could be utilized as a testing tool for evaluating the neural and/or muscular function in vivo. EMS has been proven to be more beneficial before exercise and activity due to early muscle activation. Recent studies have found that electrostimulation has been proven to be ineffective during post exercise recovery and can even lead to an increase in Delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS).

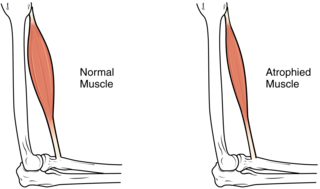

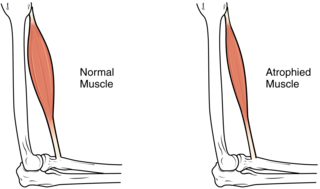

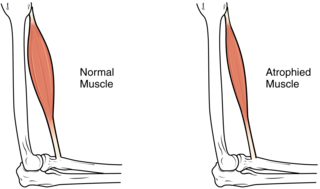

Muscle atrophy is the loss of skeletal muscle mass. It can be caused by immobility, aging, malnutrition, medications, or a wide range of injuries or diseases that impact the musculoskeletal or nervous system. Muscle atrophy leads to muscle weakness and causes disability.

Progressive overload is a method of strength training and hypertrophy training that advocates for the gradual increase of the stress placed upon the musculoskeletal and nervous system. The principle of progressive overload suggests that the continual increase in the total workload during training sessions will stimulate muscle growth and strength gain by muscle hypertrophy. This improvement in overall performance will, in turn, allow the athlete to keep increasing the intensity of their training sessions.

Muscle hypertrophy or muscle building involves a hypertrophy or increase in size of skeletal muscle through a growth in size of its component cells. Two factors contribute to hypertrophy: sarcoplasmic hypertrophy, which focuses more on increased muscle glycogen storage; and myofibrillar hypertrophy, which focuses more on increased myofibril size. It is the primary focus of bodybuilding-related activities.

Eccentric training is a type of strength training that involves using the target muscles to control weight as it moves in a downward motion. This type of training can help build muscle, improve athletic performance, and reduce the risk of injury. An eccentric contraction is the motion of an active muscle while it is lengthening under load. Eccentric training is repetitively doing eccentric muscle contractions. For example, in a biceps curl the action of lowering the dumbbell back down from the lift is the eccentric phase of that exercise – as long as the dumbbell is lowered slowly rather than letting it drop.

A myokine is one of several hundred cytokines or other small proteins and proteoglycan peptides that are produced and released by skeletal muscle cells in response to muscular contractions. They have autocrine, paracrine and/or endocrine effects; their systemic effects occur at picomolar concentrations.

Blood flow restriction training / Occlusion Training or Occlusion Training or KAATSU is an exercise and rehabilitation modality where resistance exercise, aerobic exercise or physical therapy movements are performed while using an Occlusion Cuff which is applied to the proximal aspect of the muscle on either the arms or legs. In this novel training method developed in Japan by Dr. Yoshiaki Sato in 1966, limb venous blood flow is restricted via the occlusion cuff throughout the contraction cycle and rest period. This result is partial restriction of arterial inflow to muscle, but, most significantly, it restricts venous outflow from the muscle. Given the light-load and strengthening capacity of BFR training, it can provide an effective clinical rehabilitation stimulus without the high levels of joint stress and cardiovascular risk associated with heavy-load training.

Velocity based training (VBT) is a modern approach to strength training and power training which utilises velocity tracking technology to provide rich objective data as a means to motivate and support real-time adjustments in an athlete's training plan. Typical strength and power programming and periodisation plans rely on the manipulation of reps, sets and loads as a means to calibrate training stressors in the pursuit of specific adaptations. Since the late 1990s, innovations in bar speed monitoring technology has brought velocity based training closer to the mainstream as the range of hardware and software solutions for measuring exercise velocities have become easier to use and more affordable. Velocity based training has a wide range of use cases and applications in strength and conditioning. These include barbell sports such as powerlifting and Olympic weightlifting and Crossfit, as well as rock climbing.Velocity based training is widely adopted across professional sporting clubs, with the data supporting many periodisation decisions for coaches in the weight room and on the field.

Panagiota "Nota" Klentrou is a professor at Brock University known for her research on sport training in children. She is an elected fellow of the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology.