Julia Agrippina, also referred to as Agrippina the Younger, was a Roman empress.

The Julio-Claudian dynasty comprised the first five Roman emperors: Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, and Nero.

AD 19 (XIX) was a common year starting on Sunday of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Silanus and Balbus. The denomination AD 19 for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for naming years.

Forensic science, also known as criminalistics, is the application of science to criminal and civil laws, mainly—on the criminal side—during criminal investigation, as governed by the legal standards of admissible evidence and criminal procedure.

Pathology is the study of the causes and effects of disease or injury. The word pathology also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when used in the context of modern medical treatment, the term is often used in a narrower fashion to refer to processes and tests which fall within the contemporary medical field of "general pathology", an area which includes a number of distinct but inter-related medical specialties that diagnose disease, mostly through analysis of tissue, cell, and body fluid samples. Idiomatically, "a pathology" may also refer to the predicted or actual progression of particular diseases, and the affix pathy is sometimes used to indicate a state of disease in cases of both physical ailment and psychological conditions. A physician practicing pathology is called a pathologist.

An autopsy is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner of death or to evaluate any disease or injury that may be present for research or educational purposes.. Autopsies are usually performed by a specialized medical doctor called a pathologist. In most cases, a medical examiner or coroner can determine cause of death and only a small portion of deaths require an autopsy.

Claudia Livia Julia was the only daughter of Nero Claudius Drusus and Antonia Minor and sister of the Roman Emperor Claudius and general Germanicus, and thus the paternal aunt of the emperor Caligula and maternal great-aunt of emperor Nero, as well as the niece and daughter-in-law of Tiberius. She was named after her grandmother, Augustus' wife Livia Drusilla, and commonly known by her family nickname Livilla. She was born after Germanicus and before Claudius.

Dissection is the dismembering of the body of a deceased animal or plant to study its anatomical structure. Autopsy is used in pathology and forensic medicine to determine the cause of death in humans. Less extensive dissection of plants and smaller animals preserved in a formaldehyde solution is typically carried out or demonstrated in biology and natural science classes in middle school and high school, while extensive dissections of cadavers of adults and children, both fresh and preserved are carried out by medical students in medical schools as a part of the teaching in subjects such as anatomy, pathology and forensic medicine. Consequently, dissection is typically conducted in a morgue or in an anatomy lab.

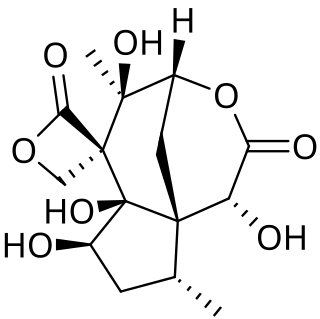

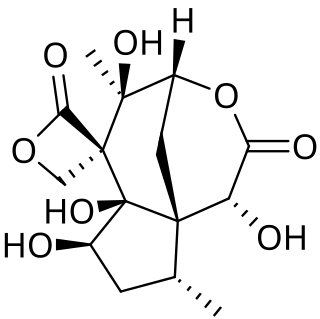

Forensic chemistry is the application of chemistry and its subfield, forensic toxicology, in a legal setting. A forensic chemist can assist in the identification of unknown materials found at a crime scene. Specialists in this field have a wide array of methods and instruments to help identify unknown substances. These include high-performance liquid chromatography, gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, atomic absorption spectroscopy, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, and thin layer chromatography. The range of different methods is important due to the destructive nature of some instruments and the number of possible unknown substances that can be found at a scene. Forensic chemists prefer using nondestructive methods first, to preserve evidence and to determine which destructive methods will produce the best results.

Collected Cases of Injustice Rectified or the Washing Away of Wrongs is a Chinese book written by Song Ci in 1247 during the Song Dynasty (960-1276) as a handbook for coroners. The author combined many historical cases of forensic science with his own experiences and wrote the book with an eye to avoiding injustice. The book was esteemed by generations of officials, and it was eventually translated into English, German, Japanese, French and other languages.

The Julii Caesares were the most illustrious family of the patrician gens Julia. The family first appears in history during the Second Punic War, when Sextus Julius Caesar was praetor in Sicily. His son, Sextus Julius Caesar, obtained the consulship in 157 BC; but the most famous descendant of this stirps is Gaius Julius Caesar, a general who conquered Gaul and became the undisputed master of Rome following the Civil War. Having been granted dictatorial power by the Roman Senate and instituting a number of political and social reforms, he was assassinated in 44 BC. After overcoming several rivals, Caesar's adopted son and heir, Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus, was proclaimed Augustus by the senate, inaugurating what became the Julio-Claudian line of Roman emperors.

Forensic biology is the application of biology to associate a person(s), whether suspect or victim, to a location, an item, another person. It can be utilized to further investigations for both criminal and civil cases. Two of the most important factors to be constantly considered throughout the collection, processing, and analysis of evidence, are the maintenance of chain of custody as well as contamination prevention, especially considering the nature of the majority of biological evidence. Forensic biology is incorporated into and is a significant aspect of numerous forensic disciplines, some of which include forensic anthropology, forensic entomology, forensic odontology, forensic pathology, forensic toxicology. When the phrase "forensic biology" is utilized, it is often regarded as synonymous with DNA analysis of biological evidence.

Criminal investigation is an applied science that involves the study of facts that are then used to inform criminal trials. A complete criminal investigation can include searching, interviews, interrogations, evidence collection and preservation, and various methods of investigation. Modern-day criminal investigations commonly employ many modern scientific techniques known collectively as forensic science.

"Autopsy" is a television series of HBO's America Undercover documentary series. Dr. Michael Baden, a real-life forensic pathologist, is the primary analyst, and has been personally involved in many of the cases that are reviewed.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to forensic science:

Halotus was an eunuch servant to the Roman Emperor Claudius, the fourth member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. He served Claudius as a taster and as a chief steward; it was because of his occupation, which entailed close contact with Claudius, that he is and was a suspect in the murder of the latter by poison. Along with Agrippina the Younger, the wife of Claudius, Halotus was considered one of the most likely to have committed the murder, although speculation by ancient historians suggest that he may have been working under orders of Agrippina.

The history of poison stretches from before 4500 BCE to the present day. Poisons have been used for many purposes across the span of human existence, most commonly as weapons, anti-venoms, and medicines. Poison has allowed much progress in branches, toxicology, and technology, among other sciences.

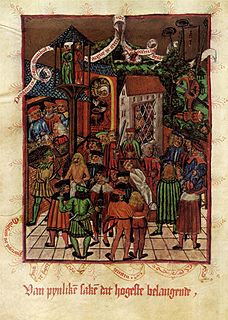

Cruentation was one of the medieval methods of finding proof against a suspected murderer. The common belief was that the body of the victim would spontaneously bleed in the presence of the murderer.

Human identification by forensic scientists can be done by three primary methods; friction ridge Analysis, DNA analysis and comparative dental analysis which is one of the roles of a forensic odontologist. It is the process of identification by a post-mortem dental examination of a deceased individual comparing these findings with the ante-mortem dental records, radiographs, study casts, etc. Believed to be those of the individual implicated assessing the concordance and/or discrepancy of the comparison of results. Teeth are resilient, and along with the highly specific and unique type, location and configuration of restorations, might be the only features used for the identification of bodies found in burnt, decomposed, skeletonised, or macerated condition.