The Creek War, was a regional conflict between opposing Native American factions, European powers, and the United States during the early 19th century. The Creek War began as a conflict within the tribes of the Muscogee, but the United States quickly became involved. British traders and Spanish colonial officials in Florida supplied the Red Sticks with weapons and equipment due to their shared interest in preventing the expansion of the United States into regions under their control.

Red Sticks —the name deriving from the red-painted war clubs of some Native American Creek—refers to an early 19th century traditionalist faction of Muscogee Creek people in the Southeastern United States. Made up mostly of Creek of the Upper Towns that supported traditional leadership and culture, as well as the preservation of communal land for cultivation and hunting, the Red Sticks arose at a time of increasing pressure on Creek territory by European American settlers. Creek of the Lower Towns were closer to the settlers, had more mixed-race families, and had already been forced to make land cessions to the Americans. In this context, the Red Sticks led a resistance movement against European American encroachment and assimilation, tensions that culminated in the outbreak of the Creek War in 1813. Initially a civil war among the Creek, the conflict drew in United States state forces while the nation was already engaged in the War of 1812 against the British.

The Battle of Talladega was fought between the Tennessee Militia and the Red Stick Creek Indians during the Creek War, in the vicinity of the present-day county and city of Talladega, Alabama, in the United States.

The Fort Mims massacre took place on August 30, 1813, at a fortified homestead site 35-40 miles north of Mobile, Alabama, during the Creek War. A large force of Creek Indians belonging to the Red Sticks faction, under the command of headmen Peter McQueen and William Weatherford, stormed the fort and defeated the militia garrison.

Fort Williams was a supply depot built in early 1814 in preparation for the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. It was located in Alabama on the southeast shore where Cedar Creek meets the Coosa River, near Talladega Springs.

James Lauderdale (1768–1814) was an American militia officer who fought in the Creek War and The Battle of New Orleans. In 1813, he joined a unit of cavalry militia under General John Coffee, commissioned as a Lieutenant-Colonel of Volunteers in the Tennessee Militia.

Fort Strother was a stockade fort at Ten Islands in the Mississippi Territory, in what is today St. Clair County, Alabama. It was located on a bluff of the Coosa River, near the modern Neely Henry Dam in Ragland, Alabama. The fort was built by General Andrew Jackson and several thousand militiamen in November 1813, during the Creek War and was named for Captain John Strother, Jackson's chief cartographer.

The Canoe Fight was a skirmish between Mississippi Territory militiamen led by Captain Samuel Dale and Red Stick warriors that took place on November 12, 1813 as part of the Creek War. The skirmish was fought largely from canoes and was a victory for the militiamen, who only had one member wounded. The victory held little military value in the overall Creek War but its participants gained widespread notoriety for their actions during the fight. The fight has been depicted in multiple illustrations, but only a historical marker currently exists near the site of the fight.

Fort Claiborne was a stockade fort built in 1813 in present-day Monroe County, Alabama during the Creek War.

Fort Armstrong was a stockade fort built in present-day Cherokee County, Alabama during the Creek War. The fort was built to protect the surrounding area from attacks by Red Stick warriors but was also used as a staging area and supply depot in preparation for further military action against the Red Sticks.

Fort Carney was a stockade fort built in 1813 in present-day Clarke County, Alabama, during the Creek War.

Chinnabee, also spelled Chinneby or Chinnibee, is an unincorporated community in Talladega County, Alabama, United States.

Fort Dale was a stockade fort built in present-day Butler County, Alabama by Alabama Territory settlers. The fort was constructed in response to Creek Indian attacks on settlers in the surrounding area.

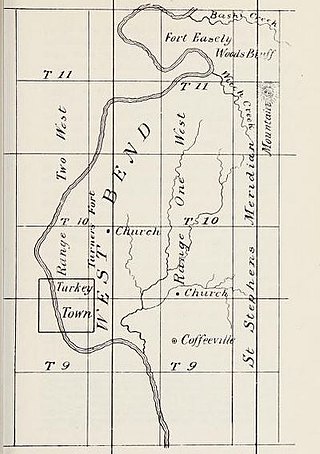

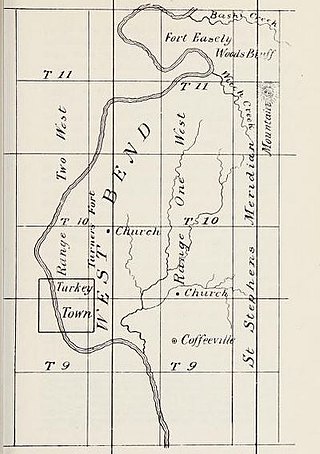

Fort Easley was a stockade fort built in 1813 in present-day Clarke County, Alabama during the Creek War.

Fort Glass was a stockade fort built in July 1813 in present-day Clarke County, Alabama during the Creek War.

Fort Hull was an earthen fort built in present-day Macon County, Alabama in 1814 during the Creek War. After the start of hostilities, the United States decided to mount an attack on Creek territory from three directions. The column advancing west from Georgia built Fort Mitchell and then clashed with the Creeks. After a pause in operations, the column from Georgia continued its march and built Fort Hull. The fort was used as a supply point and was soon abandoned after the end of the Creek War.

Fort Madison was a stockade fort built in August 1813 in present-day Clarke County, Alabama, during the Creek War, which was part of the larger War of 1812. The fort was built by the United States military in response to attacks by Creek warriors on encroaching American settlers. The fort shared many similarities to surrounding stockade forts in its construction but possessed a number of differences in its defenses. The fort housed members of the United States Army and settlers from the surrounding area, and it was used as a staging area for raids on Creek forces and supply point on further military expeditions. Fort Madison was subsequently abandoned at the conclusion of the Creek War and only a historical marker exists at the site today.

Selocta Chinnabby was a Muskogee Creek and Natchez chief from present-day Talladega County, Alabama. He allied himself with the Andrew Jackson in fighting the Red Sticks in the Creek War, which was part of the larger War of 1812.

Fort Montgomery was a stockade fort built in August 1814 in present-day Baldwin County, Alabama, during the Creek War, which was part of the larger War of 1812. The fort was built by the United States military in response to attacks by Creek warriors on encroaching American settlers and in preparation for further military action in the War of 1812. Fort Montgomery continued to be used for military purposes but in less than a decade was abandoned. Nothing exists at the site today.

Fort Pierce, was two separate stockade forts built in 1813 in present-day Baldwin County, Alabama, during the Creek War, which was part of the larger War of 1812. The fort was originally built by settlers in the Mississippi Territory to protect themselves from attacks by Creek warriors. A new fort of the same name was then built by the United States military in preparation for further action in the War of 1812, but the fort was essentially abandoned within a few years. Nothing exists at the site today.