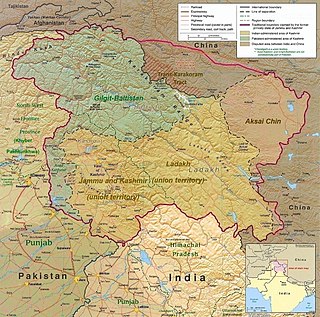

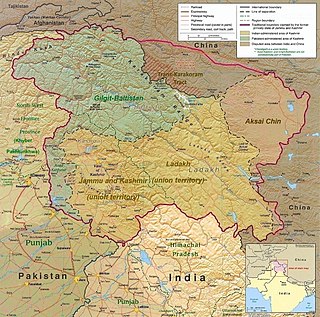

The Sino-Indian War, also known as the China–India War or the Indo-China War, was an armed conflict between China and India that took place from October to November 1962. It was a military escalation of the Sino-Indian border dispute. Fighting occurred along India's border with China, in India's North-East Frontier Agency east of Bhutan, and in Aksai Chin west of Nepal.

The McMahon Line is the boundary between Tibet and British India as agreed in the maps and notes exchanged by the respective plenipotentiaries on 24–25 March 1914 at Delhi, as part of the 1914 Simla Convention. The line delimited the respective spheres of influence of the two countries in the eastern Himalayan region along northeast India and northern Burma (Myanmar), which were earlier undefined. The Republic of China was not a party to the McMahon Line agreement, but the line was part of the overall boundary of Tibet defined in the Simla Convention, initialled by all three parties and later repudiated by the government of China. The Indian part of the Line currently serves as the de facto boundary between China and India, although its legal status is disputed by the People's Republic of China. The Burmese part of the Line was renegotiated by the People's Republic of China and Myanmar.

The Line of Actual Control (LAC), in the context of the Sino-Indian border dispute, is a notional demarcation line that separates Indian-controlled territory from Chinese-controlled territory. The concept was introduced by Chinese premier Zhou Enlai in a 1959 letter to Jawaharlal Nehru as the "line up to which each side exercises actual control", but rejected by Nehru as being incoherent. Subsequently, the term came to refer to the line formed after the 1962 Sino-Indian War.

The Trans-Karakoram Tract, also known as the Shaksgam Tract, is an area of approximately 5,200 km2 (2,000 sq mi) north of the Karakoram watershed, including the Shaksgam valley. The tract is administered by China as part of its Taxkorgan and Yecheng counties in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Although the Shaksgam tract was never under the control of Pakistan since 1947, in the 1963 Sino-Pakistan Agreement, Pakistan recognized Chinese sovereignty over the Shaksgam tract, while China recognized Pakistani sovereignty over the Gilgit Agency, and a border based on actual ground positions was recognized as the international border by China and Pakistan. It, and the entire Kashmir region, is claimed by India.

Gartok is made of twin encampment settlements of Gar Günsa and Gar Yarsa in the Gar County in the Ngari Prefecture of Tibet. Gar Gunsa served as the winter encampment and Gar Yarsa as the summer encampment. But in British nomenclature, the name Gartok was applied only to Gar Yarsa and the practice continues to date.

The Chumbi Valley, called Dromo or Tromo in Tibetan, is a valley in the Himalayas that projects southwards from the Tibetan plateau, intervening between Sikkim and Bhutan. It is coextensive with the administrative unit Yadong County in the Tibet Autonomous Region of China. The Chumbi Valley is connected to Sikkim to the southwest via the mountain passes of Nathu La and Jelep La.

A long series of events triggered the Sino-Indian War in 1962. According to John W. Garver, Chinese perceptions about the Indian designs for Tibet, and the failure to demarcate a common border between China and India were important in China's decision to fight a war with India.

The Sino-Indian border dispute is an ongoing territorial dispute over the sovereignty of two relatively large, and several smaller, separated pieces of territory between China and India. The first of the territories, Aksai Chin, is administered by China as part of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region and Tibet Autonomous Region and claimed by India as part of the union territory of Ladakh; it is mostly uninhabited high-altitude wasteland in the larger regions of Kashmir and Tibet and is crossed by the Xinjiang-Tibet Highway, but with some significant pasture lands at the margins. The other disputed territory is south of the McMahon Line, in the area formerly known as the North-East Frontier Agency and now called Arunachal Pradesh which is administered by India. The McMahon Line was part of the 1914 Simla Convention signed between British India and Tibet, without China's agreement. China disowns the agreement, stating that Tibet was never independent when it signed the Simla Convention.

The Central Institute of Higher Tibetan Studies, formerly called Central University for Tibetan Studies (CUTS), is a Deemed University founded in Sarnath, Varanasi, India, in 1967, as an autonomous organisation under Union Ministry of Culture. The CIHTS was founded by Pt. Jawahar Lal Nehru in consultation with Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama, with the aim of educating Tibetan youths in exile and Himalayan border students as well as with the aim of retranslating lost Indo-Buddhist Sanskrit texts that now existed only in Tibetan, into Sanskrit, to Hindi, and other modern Indian languages.

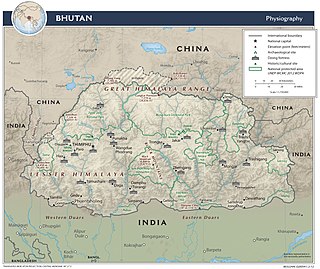

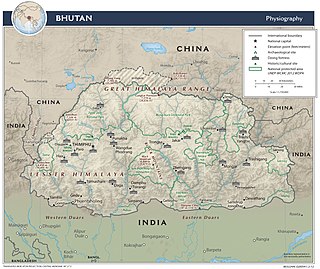

The Kingdom of Bhutan and the People's Republic of China do not maintain official diplomatic relations, and relations are historically tense. The PRC shares a contiguous border of 470 kilometers with Bhutan, and its territorial disputes with Bhutan have been a source of potential conflict. Since 1984, the two governments have conducted regular talks on border and security issues to reduce tensions.

The bilateral relation between Nepal and China is defined by the Sino-Nepalese Treaty of Peace and Friendship signed on April 28, 1960, by the two countries. Though initially unenthusiastic, Nepal has been of late making efforts to increase trade and connectivity with China. Relations between Nepal and China got a boost when both countries solved all border disputes along the China–Nepal border by signing the Sino-Nepal boundary agreement on March 21, 1960, making Nepal the first neighboring country of China to agree to and ratify a border treaty with China. The government of both Nepal and China ratified the border agreement treaty on October 5, 1961. From 1975 onward, Nepal has maintained a policy of balancing the competing influence of China and Nepal's southern neighbor India, the only two neighbors of the Himalayan country after the accession of the Kingdom of Sikkim into India in 1975.

The Dogra–Tibetan War or Sino-Sikh War was fought from May 1841 to August 1842, between the forces of the Dogra nobleman Gulab Singh of Jammu, under the suzerainty of the Sikh Empire, and those of Tibet, under the protectorate of the Qing dynasty. Gulab Singh's commander was the able general Zorawar Singh Kahluria, who, after the conquest of Ladakh, attempted to extend its boundaries in order to control the trade routes into Ladakh. Zorawar Singh's campaign, suffering from the effects of inclement weather, suffered a defeat at Taklakot (Purang) and Singh was killed. The Tibetans then advanced on Ladakh. Gulab Singh sent reinforcements under the command of his nephew Jawahir Singh. A subsequent battle near Chushul in 1842 led to a Tibetan defeat. A treaty was signed in 1842 maintaining the status quo ante bellum.

The Bhutan–China border is the international boundary between Bhutan and Tibet, China, running for 477 km (296 mi) through the Himalayas between the two tripoints with India.

The Convention of Calcutta or Anglo-Chinese Convention of 1890, officially the Convention Between Great Britain and China Relating to Sikkim and Tibet, was a treaty between Britain and Qing China relating to Tibet and the Kingdom of Sikkim. It was signed by Viceroy of India Lord Lansdowne and the Chinese Amban in Tibet, Sheng Tai, on 17 March 1890 in Calcutta, India. The Convention recognized a British protectorate over Sikkim and demarcated the Sikkim–Tibet border.

Doklam, called Donglang by China, is an area in Bhutan with a high plateau and a valley, lying between China's Chumbi Valley to the north, Bhutan's Ha District to the east and India's Sikkim state to the west. It has been depicted as part of Bhutan in the Bhutanese maps since 1961, but it is also claimed by China. The dispute has not been resolved despite several rounds of border negotiations between Bhutan and China. The area is of strategic importance to all three countries.

Tibet–India relations are said to have begun during the spread of Buddhism to Tibet from India during the 6th century AD. In 1959, the Dalai Lama fled to India after the failed 1959 Tibetan uprising. Since then, Tibetans-in-exile have been given asylum in India, with the Indian government accommodating them into 45 residential settlements across 10 states in the country. From around 150,000 Tibetan refugees in 2011, the number fell to 85,000 in 2018, according to government data. Many Tibetans are now leaving India to go back to Tibet and other countries such as United States or Germany. The Government of India, soon after India's independence in 1947, treated Tibet as a de facto independent country. However, more recently India's policy on Tibet has been mindful of Chinese sensibilities, and has recognized Tibet as a part of China.

Dhola Post was a border post set up by the Indian Army in June 1962, at a location called Che Dong, in the Namka Chu river valley area disputed by China and India. The area is now generally accepted to be north of the McMahon Line as drawn on the treaty map of 1914, but it was to the south of the Thagla Ridge, where India held the McMahon Line to lie. On 20 September, the post was attacked by Chinese forces from the Thagla Ridge in the north, and sporadic fighting continued till 20 October when an all-out attack was launched by China leading to the Sino-Indian War. Facing an overwhelming force, the Indian Army evacuated the Dhola Post as well as the entire area of Tawang, retreating to Sela and Bomdila.

The Five Fingers of Tibet is a Chinese foreign policy attributed to Mao Zedong that considers Tibet to be China's right hand palm, with five fingers on its periphery: Ladakh, Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan, and North-East Frontier Agency, that it is China's responsibility to "liberate" these regions.

Chinese irredentism refers to irredentist claims to territories of the former Chinese Empire made by the Republic of China (ROC) and subsequently the People's Republic of China (PRC).

Longju or Longzu is a disputed area in the eastern sector of the China–India border, controlled by China but claimed by India. The village of Longju is located in the Tsari Chu valley 2.5 kilometres (1.6 mi) south of the town of Migyitun, considered the historical border of Tibet. The area of Longju southwards is populated by the Tagin tribe of Arunachal Pradesh.