Glenn Theodore Seaborg was an American chemist whose involvement in the synthesis, discovery and investigation of ten transuranium elements earned him a share of the 1951 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. His work in this area also led to his development of the actinide concept and the arrangement of the actinide series in the periodic table of the elements.

The Manhattan Project was a program of research and development undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project was under the direction of Major General Leslie Groves of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Nuclear physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer was the director of the Los Alamos Laboratory that designed the bombs. The Army program was designated the Manhattan District, as its first headquarters were in Manhattan; the name gradually superseded the official codename, Development of Substitute Materials, for the entire project. The project absorbed its earlier British counterpart, Tube Alloys. The Manhattan Project employed nearly 130,000 people at its peak and cost nearly US$2 billion, over 80 percent of which was for building and operating the plants that produced the fissile material. Research and production took place at more than 30 sites across the US, the UK, and Canada.

The United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was an agency of the United States government established after World War II by the U.S. Congress to foster and control the peacetime development of atomic science and technology. President Harry S. Truman signed the McMahon/Atomic Energy Act on August 1, 1946, transferring the control of atomic energy from military to civilian hands, effective on January 1, 1947. This shift gave the members of the AEC complete control of the plants, laboratories, equipment, and personnel assembled during the war to produce the atomic bomb.

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists is a nonprofit organization concerning science and global security issues resulting from accelerating technological advances that have negative consequences for humanity. The Bulletin publishes content at both a free-access website and a bi-monthly, nontechnical academic journal. The organization has been publishing continuously since 1945, when it was founded by Albert Einstein and former Manhattan Project scientists as the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists of Chicago immediately following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The organization is also the keeper of the symbolic Doomsday Clock, the time of which is announced each January.

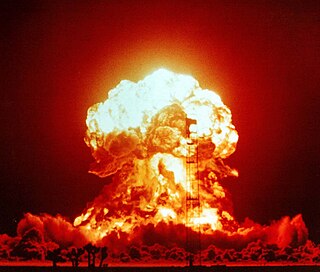

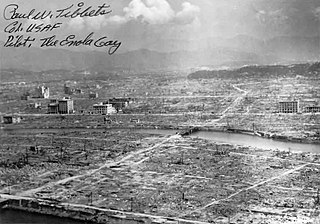

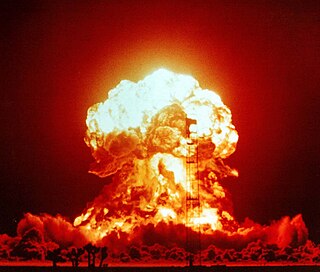

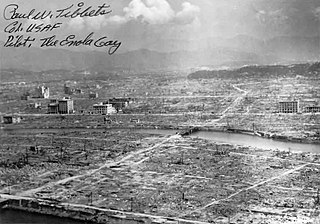

Building on major scientific breakthroughs made during the 1930s, the United Kingdom began the world's first nuclear weapons research project, codenamed Tube Alloys, in 1941, during World War II. The United States, in collaboration with the United Kingdom, initiated the Manhattan Project the following year to build a weapon using nuclear fission. The project also involved Canada. In August 1945, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were conducted by the United States, with British consent, against Japan at the close of that war, standing to date as the only use of nuclear weapons in hostilities.

The Interim Committee was a secret high-level group created in May 1945 by United States Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson at the urging of leaders of the Manhattan Project and with the approval of President Harry S. Truman to advise on matters pertaining to nuclear energy. Composed of prominent political, scientific and industrial figures, the Interim Committee had broad terms of reference which included advising the President on wartime controls and the release of information, and making recommendations on post-war controls and policies related to nuclear energy, including legislation. Its first duty was to advise on the manner in which nuclear weapons should be employed against Japan. Later, it advised on legislation for the control and regulation of nuclear energy. It was named "Interim" in anticipation of a permanent body that would later replace it after the war, where the development of nuclear technology would be placed firmly under civilian control. The Atomic Energy Commission was enacted in 1946 to serve this function.

The nuclear weapons debate refers to the controversies surrounding the threat, use and stockpiling of nuclear weapons. Even before the first nuclear weapons had been developed, scientists involved with the Manhattan Project were divided over the use of the weapon. The only time nuclear weapons have been used in warfare was during the final stages of World War II when USAAF B-29 Superfortress bombers dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in early August 1945. The role of the bombings in Japan's surrender and the U.S.'s ethical justification for them have been the subject of scholarly and popular debate for decades.

The Metallurgical Laboratory was a scientific laboratory at the University of Chicago that was established in February 1942 to study and use the newly discovered chemical element plutonium. It researched plutonium's chemistry and metallurgy, designed the world's first nuclear reactors to produce it, and developed chemical processes to separate it from other elements. In August 1942 the lab's chemical section was the first to chemically separate a weighable sample of plutonium, and on 2 December 1942, the Met Lab produced the first controlled nuclear chain reaction, in the reactor Chicago Pile-1, which was constructed under the stands of the university's old football stadium, Stagg Field.

The Manhattan Project was a research and development project that produced the first atomic bombs during World War II. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project was under the direction of Major General Leslie Groves of the US Army Corps of Engineers. The Army component of the project was designated the Manhattan District; "Manhattan" gradually became the codename for the entire project. Along the way, the project absorbed its earlier British counterpart, Tube Alloys. The Manhattan Project began modestly in 1939, but grew to employ more than 130,000 people and cost nearly US$2 billion. Over 90% of the cost was for building factories and producing the fissionable materials, with less than 10% for development and production of the weapons.

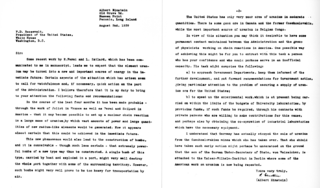

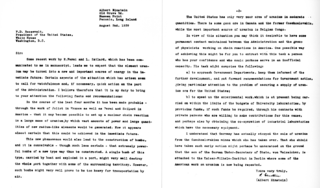

The Einstein–Szilard letter was a letter written by Leo Szilard and signed by Albert Einstein on August 2, 1939, that was sent to President of the United States Franklin D. Roosevelt. Written by Szilard in consultation with fellow Hungarian physicists Edward Teller and Eugene Wigner, the letter warned that Germany might develop atomic bombs and suggested that the United States should start its own nuclear program. It prompted action by Roosevelt, which eventually resulted in the Manhattan Project, the development of the first atomic bombs, and the use of these bombs on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The Szilárd petition, drafted and circulated in July 1945 by scientist Leo Szilard, was signed by 70 scientists working on the Manhattan Project in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and the Metallurgical Laboratory in Chicago, Illinois. It asked President Harry S. Truman to inform Japan of the terms of surrender demanded by the allies, and allow Japan to either accept or refuse these terms, before America used atomic weapons. However, the petition never made it through the chain of command to President Truman. It was not declassified and made public until 1961.

The S-1 Executive Committee laid the groundwork for the Manhattan Project by initiating and coordinating the early research efforts in the United States, and liaising with the Tube Alloys Project in Britain.

Eugene Rabinowitch was a Russian-born American biophysicist who is known for his work in photosynthesis and nuclear energy. He was a co-author of the Franck Report and a co-founder in 1945 of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, a global security and public policy magazine, which he edited until his death.

The Report on the International Control of Atomic Energy was written by a committee chaired by Dean Acheson and David Lilienthal in 1946 and is generally known as the Acheson–Lilienthal Report or Plan. The report was an important American document that appeared just before the intensification of the early Cold War. It proposed the international control of nuclear weapons and the avoidance of future nuclear warfare. A version, the Baruch Plan, was vetoed by the Soviets at the United Nations.

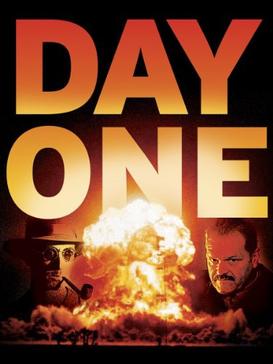

Day One is a made-for-TV docudrama film about The Manhattan Project, the research and development of the atomic bomb during World War II. It is based on the book by Peter Wyden. The film was written by David W. Rintels and directed by Joseph Sargent. It starred Brian Dennehy as General Leslie Groves, David Strathairn as Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer and Michael Tucker as Dr. Leo Szilard. It premiered in the United States on March 5, 1989 on the CBS network. It won the 1989 Emmy award for Outstanding Drama/Comedy Special. The movie received critical acclaim for its historical accuracy despite being a drama.

Lawrence Elgin Glendenin was an American chemist who co-discovered the element promethium.

Charles DuBois Coryell was an American chemist who was one of the discoverers of the element promethium.

"My Trial as a War Criminal" is a 1949 short story by atomic physicist Leo Szilard. Szilard had played a leading role in the Manhattan Project, and in the story he imagines the kind of show trial he might have had if he had been prosecuted in a manner similar to the Nuremberg Trials. Szilard earlier drafted the letter Albert Einstein signed, to Franklin Roosevelt, suggesting the US develop the military uses of nuclear power, and later the petition unsuccessfully advocating against the use of nuclear weapons.

Donald James Hughes was an American nuclear physicist, chiefly notable as one of the signers off the Franck Report in June, 1945, recommending that the United States not use the atomic bomb as a weapon to prompt the surrender of Japan in World War II.

David Lawrence Hill was an American nuclear physicist who worked on the Manhattan Project in World War II and was head of the Federation of American Scientists. He is best known for his 1959 testimony against the nomination of Lewis Strauss as United States Secretary of Commerce.