In meteorology, a cyclone is a large air mass that rotates around a strong center of low atmospheric pressure, counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere as viewed from above. Cyclones are characterized by inward-spiraling winds that rotate about a zone of low pressure. The largest low-pressure systems are polar vortices and extratropical cyclones of the largest scale. Warm-core cyclones such as tropical cyclones and subtropical cyclones also lie within the synoptic scale. Mesocyclones, tornadoes, and dust devils lie within the smaller mesoscale. Upper level cyclones can exist without the presence of a surface low, and can pinch off from the base of the tropical upper tropospheric trough during the summer months in the Northern Hemisphere. Cyclones have also been seen on extraterrestrial planets, such as Mars, Jupiter, and Neptune. Cyclogenesis is the process of cyclone formation and intensification. Extratropical cyclones begin as waves in large regions of enhanced mid-latitude temperature contrasts called baroclinic zones. These zones contract and form weather fronts as the cyclonic circulation closes and intensifies. Later in their life cycle, extratropical cyclones occlude as cold air masses undercut the warmer air and become cold core systems. A cyclone's track is guided over the course of its 2 to 6 day life cycle by the steering flow of the subtropical jet stream.

A subtropical cyclone is a weather system that has some characteristics of both tropical and an extratropical cyclone.

In fluid dynamics, a vortex is a region in a fluid in which the flow revolves around an axis line, which may be straight or curved. Vortices form in stirred fluids, and may be observed in smoke rings, whirlpools in the wake of a boat, and the winds surrounding a tropical cyclone, tornado or dust devil.

The 1976 Atlantic hurricane season was an fairly average Atlantic hurricane season in which 21 tropical or subtropical cyclones formed. 10 of them became nameable storms. Six of those reached hurricane strength, with two of the six became major hurricanes, which are Category 3 or higher on the Saffir–Simpson scale. The season officially began on June 1 and lasted until November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin. However, the first system, a subtropical storm, developed in the Gulf of Mexico on May 21, several days before the official start of the season. The system spawned nine tornadoes in Florida, resulting in about $628,000 (1976 USD) in damage, though impact was minor otherwise.

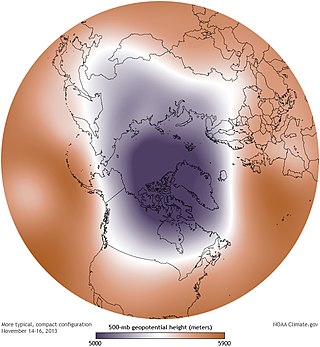

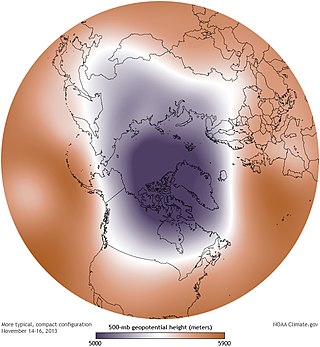

A circumpolar vortex, or simply polar vortex, is a large region of cold, rotating air that encircles both of Earth's polar regions. Polar vortices also exist on other rotating, low-obliquity planetary bodies. The term polar vortex can be used to describe two distinct phenomena; the stratospheric polar vortex, and the tropospheric polar vortex. The stratospheric and tropospheric polar vortices both rotate in the direction of the Earth's spin, but they are distinct phenomena that have different sizes, structures, seasonal cycles, and impacts on weather.

A funnel cloud is a funnel-shaped cloud of condensed water droplets, associated with a rotating column of wind and extending from the base of a cloud but not reaching the ground or a water surface. A funnel cloud is usually visible as a cone-shaped or needle like protuberance from the main cloud base. Funnel clouds form most frequently in association with supercell thunderstorms, and are often, but not always, a visual precursor to tornadoes. Funnel clouds are visual phenomena, these are not the vortex of wind itself.

A mesoscale convective system (MCS) is a complex of thunderstorms that becomes organized on a scale larger than the individual thunderstorms but smaller than extratropical cyclones, and normally persists for several hours or more. A mesoscale convective system's overall cloud and precipitation pattern may be round or linear in shape, and include weather systems such as tropical cyclones, squall lines, lake-effect snow events, polar lows, and mesoscale convective complexes (MCCs), and generally forms near weather fronts. The type that forms during the warm season over land has been noted across North and South America, Europe, and Asia, with a maximum in activity noted during the late afternoon and evening hours.

A tropical upper tropospheric trough (TUTT), also known as the mid-oceanic trough, is a trough situated in the upper-level tropics. Its formation is usually caused by the intrusion of energy and wind from the mid-latitudes into the tropics. It can also develop from the inverted trough adjacent to an upper level anticyclone. TUTTs are different from mid-latitude troughs in the sense that they are maintained by subsidence warming near the tropopause which balances radiational cooling. When strong, they can present a significant vertical wind shear to the tropics and subdue tropical cyclogenesis. When upper cold lows break off from their base, they tend to retrograde and force the development of, or enhance, surface troughs and tropical waves to their east. Under special circumstances, they can induce thunderstorm activity and lead to the formation of tropical cyclones.

The eye is a region of mostly calm weather at the center of a tropical cyclone. The eye of a storm is a roughly circular area, typically 30–65 kilometers in diameter. It is surrounded by the eyewall, a ring of towering thunderstorms where the most severe weather and highest winds of the cyclone occur. The cyclone's lowest barometric pressure occurs in the eye and can be as much as 15 percent lower than the pressure outside the storm.

Tropical cyclogenesis is the development and strengthening of a tropical cyclone in the atmosphere. The mechanisms through which tropical cyclogenesis occurs are distinctly different from those through which temperate cyclogenesis occurs. Tropical cyclogenesis involves the development of a warm-core cyclone, due to significant convection in a favorable atmospheric environment.

The 1996 Lake Huron cyclone, commonly referred to as Hurricane Huron and Hurroncane, was an extremely rare, strong cyclonic storm system that developed over Lake Huron in September 1996. The system resembled a subtropical cyclone at its peak, bearing some characteristics of a tropical cyclone. It was the first time such a storm has ever been recorded forming over the Great Lakes region.

Tornadogenesis is the process by which a tornado forms. There are many types of tornadoes and these vary in methods of formation. Despite ongoing scientific study and high-profile research projects such as VORTEX, tornadogenesis is a volatile process and the intricacies of many of the mechanisms of tornado formation are still poorly understood.

Extratropical cyclones, sometimes called mid-latitude cyclones or wave cyclones, are low-pressure areas which, along with the anticyclones of high-pressure areas, drive the weather over much of the Earth. Extratropical cyclones are capable of producing anything from cloudiness and mild showers to severe gales, thunderstorms, blizzards, and tornadoes. These types of cyclones are defined as large scale (synoptic) low pressure weather systems that occur in the middle latitudes of the Earth. In contrast with tropical cyclones, extratropical cyclones produce rapid changes in temperature and dew point along broad lines, called weather fronts, about the center of the cyclone.

A tropical cyclone is a rapidly rotating storm system characterized by a low-pressure center, a closed low-level atmospheric circulation, strong winds, and a spiral arrangement of thunderstorms that produce heavy rain and squalls. Depending on its location and strength, a tropical cyclone is referred to by different names, including hurricane, typhoon, tropical storm, cyclonic storm, tropical depression, or simply cyclone. A hurricane is a strong tropical cyclone that occurs in the Atlantic Ocean or northeastern Pacific Ocean, and a typhoon occurs in the northwestern Pacific Ocean. In the Indian Ocean and South Pacific, comparable storms are referred to as "tropical cyclones", and such storms in the Indian Ocean can also be called "severe cyclonic storms".

An upper tropospheric cyclonic vortex is a vortex, or a circulation with a definable center, that usually moves slowly from east-northeast to west-southwest and is prevalent across Northern Hemisphere's warm season. Its circulations generally do not extend below 6,080 metres (19,950 ft) in altitude, as it is an example of a cold-core low. A weak inverted wave in the easterlies is generally found beneath it, and it may also be associated with broad areas of high-level clouds. Downward development results in an increase of cumulus clouds and the appearance of circulation at ground level. In rare cases, a warm-core cyclone can develop in its associated convective activity, resulting in a tropical cyclone and a weakening and southwest movement of the nearby upper tropospheric cyclonic vortex. Symbiotic relationships can exist between tropical cyclones and the upper level lows in their wake, with the two systems occasionally leading to their mutual strengthening. When they move over land during the warm season, an increase in monsoon rains occurs.

Inflow is the flow of a fluid into a large collection of that fluid. Within meteorology, inflow normally refers to the influx of warmth and moisture from air within the Earth's atmosphere into storm systems. Extratropical cyclones are fed by inflow focused along their cold front and warm fronts. Tropical cyclones require a large inflow of warmth and moisture from warm oceans in order to develop significantly, mainly within the lowest 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) of the atmosphere. Once the flow of warm and moist air is cut off from thunderstorms and their associated tornadoes, normally by the thunderstorm's own rain-cooled outflow boundary, the storms begin to dissipate. Rear inflow jets behind squall lines act to erode the broad rain shield behind the squall line, and accelerate its forward motion.

In meteorology, eyewall replacement cycles, also called concentric eyewall cycles, naturally occur in intense tropical cyclones, generally with winds greater than 185 km/h (115 mph), or major hurricanes. When tropical cyclones reach this intensity, and the eyewall contracts or is already small, some of the outer rainbands may strengthen and organize into a ring of thunderstorms—a new, outer eyewall—that slowly moves inward and robs the original, inner eyewall of its needed moisture and angular momentum. Since the strongest winds are in a tropical cyclone's eyewall, the storm usually weakens during this phase, as the inner wall is "choked" by the outer wall. Eventually the outer eyewall replaces the inner one completely, and the storm may re-intensify.

A cold-core low, also known as an upper level low or cold-core cyclone, is a cyclone aloft which has an associated cold pool of air residing at high altitude within the Earth's troposphere, without a frontal structure. It is a low pressure system that strengthens with height in accordance with the thermal wind relationship. If a weak surface circulation forms in response to such a feature at subtropical latitudes of the eastern north Pacific or north Indian oceans, it is called a subtropical cyclone. Cloud cover and rainfall mainly occurs with these systems during the day.

Cyclolysis is a process in which a cyclonic circulation weakens and deteriorates. Cyclolysis is the opposite of cyclogenesis.