Related Research Articles

Classical Chinese, also known as Literary Chinese, is the language of the classic literature from the end of the Spring and Autumn period through to the end of the Han dynasty, a written form of Old Chinese. Classical Chinese is a traditional style of written Chinese that evolved from the classical language, making it different from any modern spoken form of Chinese. Literary Chinese was used for almost all formal writing in China until the early 20th century, and also, during various periods, in Japan, Korea and Vietnam. Among Chinese speakers, Literary Chinese has been largely replaced by written vernacular Chinese, a style of writing that is similar to modern spoken Mandarin Chinese, while speakers of non-Chinese languages have largely abandoned Literary Chinese in favor of their respective local vernaculars. Although languages have evolved in unique, different directions from the base of Literary Chinese, many cognates can be still found between these languages that have historically written in Classical Chinese.

Early works of Japanese literature were heavily influenced by cultural contact with China and Chinese literature, and were often written in Classical Chinese. Indian literature also had an influence through the spread of Buddhism in Japan. In the Heian period, Japan's original kokufū culture developed and literature also established its own style. Following Japan's reopening of its ports to Western trading and diplomacy in the 19th century, Western literature has influenced the development of modern Japanese writers, while they have in turn been more recognized outside Japan, with two Nobel Prizes so far, as of 2020.

Written vernacular Chinese, also known as Baihua, is the forms of written Chinese based on the varieties of Chinese spoken throughout China, in contrast to Classical Chinese, the written standard used during imperial China up to the early twentieth century. A written vernacular based on Mandarin Chinese was used in novels in the Ming and Qing dynasties, and later refined by intellectuals associated with the May Fourth Movement. Since the early 1920s, this modern vernacular form has been the standard style of writing for speakers of all varieties of Chinese throughout mainland China, Taiwan, Malaysia, and Singapore as the written form of Modern Standard Chinese. This is commonly called Standard Written Chinese or Modern Written Chinese to avoid ambiguity with spoken vernaculars, with the written vernaculars of earlier eras, and with other written vernaculars such as written Cantonese or written Hokkien.

A literary language is the form of a language used in its literary writing. It can be either a nonstandard dialect or a standardized variety of the language. It can sometimes differ noticeably from the various spoken lects, but the difference between literary and non-literary forms is greater in some languages than in others. If there is a strong divergence between a written form and the spoken vernacular, the language is said to exhibit diglossia.

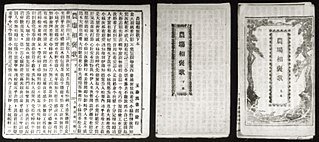

A Kanbun is a form of Classical Chinese used in Japan from the Nara period to the mid-20th century. Much of Japanese literature was written in this style and it was the general writing style for official and intellectual works throughout the period. As a result, Sino-Japanese vocabulary makes up a large portion of the Japanese lexicon and much classical Chinese literature is accessible to Japanese readers in some semblance of the original. The corresponding system in Korean is gugyeol (口訣/구결).

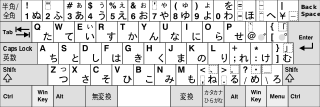

The modern Japanese writing system uses a combination of logographic kanji, which are adopted Chinese characters, and syllabic kana. Kana itself consists of a pair of syllabaries: hiragana, used primarily for native or naturalised Japanese words and grammatical elements; and katakana, used primarily for foreign words and names, loanwords, onomatopoeia, scientific names, and sometimes for emphasis. Almost all written Japanese sentences contain a mixture of kanji and kana. Because of this mixture of scripts, in addition to a large inventory of kanji characters, the Japanese writing system is considered to be one of the most complicated in current use.

The classical Japanese language, also called "old writing", is the literary form of the Japanese language that was the standard until the early Shōwa period (1926–1989). It is based on Early Middle Japanese, the language as spoken during the Heian period (794–1185), but exhibits some later influences. Its use started to decline during the late Meiji period (1868–1912) when novelists started writing their works in the spoken form. Eventually, the spoken style came into widespread use, including in major newspapers, but many official documents were still written in the old style. After the end of World War II, most documents switched to the spoken style, although the classical style continues to be used in traditional genres, such as haiku and waka. Old laws are also left in the classical style unless fully revised.

Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) or Modern Written Arabic, terms used mostly by Western linguists, is the variety of standardized, literary Arabic that developed in the Arab world in the late 19th and early 20th centuries; occasionally, it also refers to spoken Arabic that approximates this written standard. MSA is the language used in academia, print and mass media, law and legislation, though it is generally not spoken as a first language, similar to Classical Latin. It is a pluricentric standard language taught throughout the Arab world in formal education, differing significantly from many vernacular varieties of Arabic that are commonly spoken as mother tongues in the area; these are only partially mutually intelligible with both MSA and with each other depending on their proximity in the Arabic dialect continuum.

Written Cantonese is the written form of Cantonese, the most complete written form of Chinese after that for Mandarin Chinese and Classical Chinese. Written Chinese was originally developed for Classical Chinese, and was the main literary language of China until the 19th century. Written vernacular Chinese first appeared in the 17th century and a written form of Mandarin became standard throughout China in the early 20th century. While the Mandarin form can in principle be read and spoken word for word in other Chinese varieties, its intelligibility to non-Mandarin speakers is poor to incomprehensible because of differences in idioms, grammar and usage. Modern Cantonese speakers have therefore developed new characters for words that do not exist and have retained others that have been lost in standard Chinese.

The languages of Taiwan consist of several varieties of languages under the families of Austronesian languages and Sino-Tibetan languages. The Formosan languages, a branch of Austronesian languages, have been spoken by the Taiwanese aborigines in Taiwan for thousands of years. Owing to the wide internal variety of the Formosan languages, research on historical linguistics recognizes Taiwan as the Urheimat (homeland) of the whole Austronesian languages family. In the last 400 years, several waves of Hans emigrations brought several different Sino-Tibetan languages into Taiwan. These languages include Taiwanese Hokkien, Hakka, and Mandarin, which have become the major languages spoken in Taiwan nowadays.

The most widely spoken language in Japan is Japanese, which is separated into several dialects with Tokyo dialect considered standard Japanese.

Hokkien, a Min Nan variety of Chinese spoken in Southeastern China, Taiwan and Southeast Asia, does not have a unitary standardized writing system, in comparison with the well-developed written forms of Cantonese and Vernacular Chinese (Mandarin). In Taiwan, a standard for Written Hokkien has been developed by the Republic of China Ministry of Education including its Dictionary of Frequently-Used Taiwan Minnan, but there are a wide variety of different methods of writing in Vernacular Hokkien. Nevertheless, vernacular works written in the Hokkien are still commonly seen in literature, film, performing arts and music.

Modern Chinese poetry, including New poetry, refers to post Qing Dynasty Chinese poetry, including the modern vernacular (baihua) style of poetry increasingly common with the New Culture and 4 May 1919 movements, with the development of experimental styles such as "free verse" ; but, also including twentieth and twenty-first century continuations or revivals of Classical Chinese poetry forms. Some modern Chinese poetry represents major new and modern developments in the poetry of one of the world's larger areas, as well as other important areas sharing this linguistic affinity. One of the first writers of poetry in the modern Chinese poetry mode was Hu Shih (1891–1962).

Kaidan Botan Dōrō (怪談牡丹燈籠) is a story inspired by the Chinese influenced kaidan Botan Dōrō. Published as a stenography narrated and created by the rakugo artist San'yūtei Enchō and written with the aid of both Sakai Shōzō (酒井昇造) and Wakabayashi Kanzō (若林玵蔵). Published in 1886, it is considered a famous kaidan in Japan.

Shiba Shirō (柴四郎), better known for his pen name Tōkai Sanshi, was a famous political activist and novelist during the Meiji period. He was born into a samurai family and fought for domain of Aizu during the Boshin War from 1868 to 1869, after which the Aizu domain was abandoned. He was educated at different facilities in Japan and in the United States, and he served in the military during the First Sino-Japanese War and Russo-Japanese War. His major works include Strange Encounters with Beautiful Women, first serialized in 1885 and concluded in 1897.

Viscount Yasushi Nomura was a Japanese bureaucrat, statesman and cabinet minister, active in Meiji period Japan

Chinese-language literature in Korea is literature written the Chinese language in Korea, which represents an early phase of Korean literature and influenced literature in the Korean language.

Chinese writing, culture and institutions were imported as a whole by Vietnam, Korea, Japan and other neighbouring states over an extended period. Chinese Buddhism spread over East Asia between the 2nd and 5th centuries AD, followed by Confucianism as these countries developed strong central governments modelled on Chinese institutions. In Vietnam and Korea, and for a shorter time in Japan and the Ryukyus, scholar-officials were selected using examinations on the Confucian classics modelled on the Chinese civil service examinations. Shared familiarity with the Chinese classics and Confucian values provided a common framework for intellectuals and ruling elites across the region. All of this was based on the use of Literary Chinese, which became the medium of scholarship and government across the region. Although each of these countries developed vernacular writing systems and used them for popular literature, they continued to use Chinese for all formal writing until it was swept away by rising nationalism around the end of the 19th century.

Yamada Bimyō, born Yamada Taketarō, was a Japanese novelist.

Shintaishi (新体詩) is a type of Japanese poetry. It specifically refers to poems written in classical Japanese in non-traditional forms in the Meiji period. Notable practitioners of the form included Yuasa Banketsu and Ochiai Naobumi. It declined in popularity in the first two decades of the twentieth century, in favour of free-form poetry in a more vernacular form of Japanese.

References

- ↑ Twine, Nanette. (Autumn 1978) "Gembun Itchi" Monumenta Nipponica p.334– 335.

- ↑ Komai, Akira. (1983) "Classical Japanese" Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan Volume 1 pp.321–322.

- ↑ Twine, p.339–340.

- ↑ Twine, p.337–338.

- ↑ Neustupny, JV. (1983) "Gembun Itchi" Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan Volume 3 p.16.

- ↑ Neustupny, JV. p.16.

- ↑ Twine, pp. 347, 352.

- ↑ Twine, p. 353.

- ↑ Twine, p. 354.

- ↑ Neustupny, JV. p.16.

- ↑ Trantor, Nicholas and Kizu, Mika. (2012) "Modern Japanese" The Languages of Japan and Korea ed. Nicolas Trantor p.268.