Genius is a characteristic of original and exceptional insight in the performance of some art or endeavor that surpasses expectations, sets new standards for the future, establishes better methods of operation, or remains outside the capabilities of competitors. Genius is associated with intellectual ability and creative productivity. The term genius can also be used to refer to people characterised by genius, and/or to polymaths who excel across many subjects.

An intelligence quotient (IQ) is a total score derived from a set of standardised tests or subtests designed to assess human intelligence. The abbreviation "IQ" was coined by the psychologist William Stern for the German term Intelligenzquotient, his term for a scoring method for intelligence tests at University of Breslau he advocated in a 1912 book.

William Bradford Shockley Jr. was an American inventor, physicist, and eugenicist. He was the manager of a research group at Bell Labs that included John Bardeen and Walter Brattain. The three scientists were jointly awarded the 1956 Nobel Prize in Physics for "their researches on semiconductors and their discovery of the transistor effect".

Alfred Binet, born Alfredo Binetti, was a French psychologist who invented the first practical IQ test, the Binet–Simon test. In 1904, the French Ministry of Education asked psychologist Alfred Binet to devise a method that would determine which students did not learn effectively from regular classroom instruction so they could be given remedial work. Along with his collaborator Théodore Simon, Binet published revisions of his test in 1908 and 1911, the last of which appeared just before his death.

The Stanford–Binet Intelligence Scales is an individually administered intelligence test that was revised from the original Binet–Simon Scale by Alfred Binet and Théodore Simon. It is in its fifth edition (SB5), which was released in 2003.

Intellectual giftedness is an intellectual ability significantly higher than average. It is a characteristic of children, variously defined, that motivates differences in school programming. It is thought to persist as a trait into adult life, with various consequences studied in longitudinal studies of giftedness over the last century. These consequences sometimes include stigmatizing and social exclusion. There is no generally agreed definition of giftedness for either children or adults, but most school placement decisions and most longitudinal studies over the course of individual lives have followed people with IQs in the top 2.5 percent of the population—that is, IQs above 130. Definitions of giftedness also vary across cultures.

Gifted education is a sort of education used for children who have been identified as gifted and talented.

The Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) is an IQ test designed to measure intelligence and cognitive ability in adults and older adolescents.

Lewis Madison Terman was an American psychologist, academic, and proponent of eugenics. He was noted as a pioneer in educational psychology in the early 20th century at the Stanford School of Education. Terman is best known for his revision of the Stanford–Binet Intelligence Scales and for initiating the longitudinal study of children with high IQs called the Genetic Studies of Genius. As a prominent eugenicist, he was a member of the Human Betterment Foundation, the American Eugenics Society, and the Eugenics Research Association. He also served as president of the American Psychological Association. A Review of General Psychology survey, published in 2002, ranked Terman as the 72nd most cited psychologist of the 20th century, in a tie with G. Stanley Hall.

Catharine Morris Cox Miles was an American psychologist known for her work on intelligence and genius. Born in San Jose, CA, to Lydia Shipley Bean and Charles Elwood Cox. In 1927 married psychologist Walter Richard Miles. Her sister was classics scholar and Quaker administrator Anna Cox Brinton.

A high-IQ society is an organization that limits its membership to people who have attained a specified score on an IQ test, usually in the top two percent of the population or above. These may also be referred to as genius societies. The largest and oldest such society is Mensa International, which was founded by Roland Berrill and Lancelot Ware in 1946.

Mental age is a concept related to intelligence. It looks at how a specific individual, at a specific age, performs intellectually, compared to average intellectual performance for that individual's actual chronological age (i.e. time elapsed since birth). The intellectual performance is based on performance in tests and live assessments by a psychologist. The score achieved by the individual is compared to the median average scores at various ages, and the mental age (x, say) is derived such that the individual's score equates to the average score at age x.

Florence Laura Goodenough was an American psychologist and professor at the University of Minnesota who studied child intelligence and various problems in the field of child development. She was president of the Society for Research in Child Development from 1946-1947. She is best known for published book The Measurement of Intelligence, where she introduced the Goodenough Draw-A-Man test to assess intelligence in young children through nonverbal measurement. She is noted for developing the Minnesota Preschool Scale. In 1931 she published two notable books titled Experimental Child Study and Anger in Young Children which analyzed the methods used in evaluating children. She wrote the Handbook of Child Psychology in 1933, becoming the first known psychologist to critique ratio I.Q.

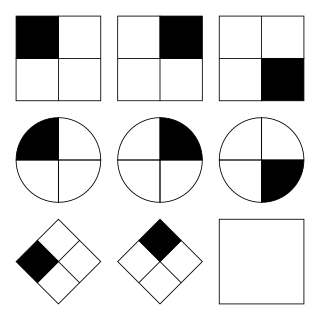

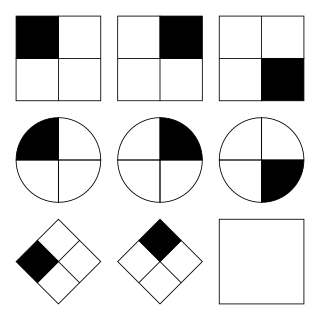

IQ classification is the practice of categorizing human intelligence, as measured by intelligence quotient (IQ) tests, into categories such as "superior" or "average".

Leta Stetter Hollingworth was an American psychologist, educator, and feminist. Hollingworth also made contributions in psychology of women, clinical psychology, and educational psychology. She is best known for her work with gifted children.

Robert Richardson Sears was an American psychologist who specialized in child psychology and the psychology of personality. He was the head of the psychology department at Stanford and later dean of the School of Humanities and Sciences there, continued the long-term I.Q. studies of Lewis Madison Terman at Stanford, and authored many pivotal papers and books on various aspects of psychology.

Quinn Michael McNemar was an American psychologist and statistician. He is known for his work on IQ tests, for his book Psychological Statistics (1949) and for McNemar's test, the statistical test he introduced in 1947.

The McCarthy Scales of Children's Abilities (MSCA) is a psychological test given to young children. "the McCarthy scales present a carefully constructed individual test of human ability."

Maud Amanda Merrill was an American psychologist. Both an alumna and faculty member of Stanford University, Merrill worked with Lewis Terman to develop the second and third editions of the Stanford–Binet Intelligence Scales.

Barbara Stoddard Burks was an American psychologist known for her research on the nature-nurture debate as it pertained to intelligence and other human traits. She has been credited with "...pioneer[ing] the statistical techniques which continue to ground the trenchant nature/nurture debates about intelligence in American psychology."