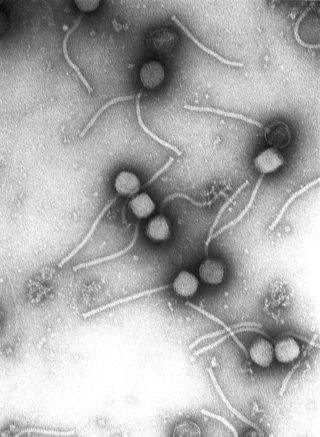

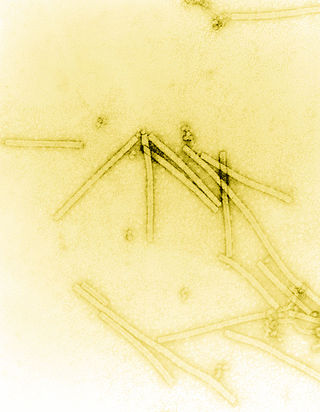

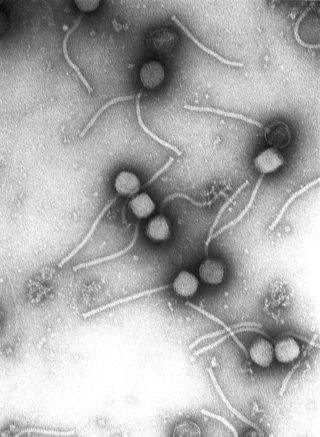

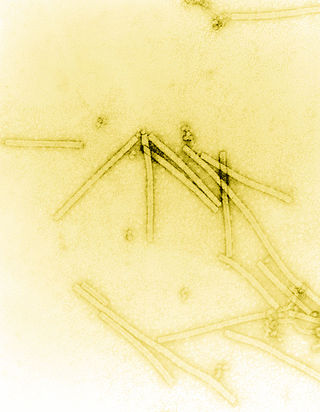

A bacteriophage, also known informally as a phage, is a duplodnaviria virus that infects and replicates within bacteria and archaea. The term was derived from "bacteria" and the Greek φαγεῖν, meaning "to devour". Bacteriophages are composed of proteins that encapsulate a DNA or RNA genome, and may have structures that are either simple or elaborate. Their genomes may encode as few as four genes and as many as hundreds of genes. Phages replicate within the bacterium following the injection of their genome into its cytoplasm.

Virology is the scientific study of biological viruses. It is a subfield of microbiology that focuses on their detection, structure, classification and evolution, their methods of infection and exploitation of host cells for reproduction, their interaction with host organism physiology and immunity, the diseases they cause, the techniques to isolate and culture them, and their use in research and therapy.

Félix d'Hérelle was a French microbiologist. He was co-discoverer of bacteriophages and experimented with the possibility of phage therapy. D'Herelle has also been credited for his contributions to the larger concept of applied microbiology.

Phage therapy, viral phage therapy, or phagotherapy is the therapeutic use of bacteriophages for the treatment of pathogenic bacterial infections. This therapeutic approach emerged at the beginning of the 20th century but was progressively replaced by the use of antibiotics in most parts of the world after the Second World War. Bacteriophages, known as phages, are a form of virus that attach to bacterial cells and inject their genome into the cell. The bacteria's production of the viral genome interferes with its ability to function, halting the bacterial infection. The bacterial cell causing the infection is unable to reproduce and instead produces additional phages. Phages are very selective in the strains of bacteria they are effective against.

Escherichia virus T4 is a species of bacteriophages that infect Escherichia coli bacteria. It is a double-stranded DNA virus in the subfamily Tevenvirinae from the family Myoviridae. T4 is capable of undergoing only a lytic lifecycle and not the lysogenic lifecycle. The species was formerly named T-even bacteriophage, a name which also encompasses, among other strains, Enterobacteria phage T2, Enterobacteria phage T4 and Enterobacteria phage T6.

Bacteriophage T7 is a bacteriophage, a virus that infects bacteria. It infects most strains of Escherichia coli and relies on these hosts to propagate. Bacteriophage T7 has a lytic life cycle, meaning that it destroys the cell it infects. It also possesses several properties that make it an ideal phage for experimentation: its purification and concentration have produced consistent values in chemical analyses; it can be rendered noninfectious by exposure to UV light; and it can be used in phage display to clone RNA binding proteins.

Bacteriophage (phage) are viruses of bacteria and arguably are the most numerous "organisms" on Earth. The history of phage study is captured, in part, in the books published on the topic. This is a list of over 100 monographs on or related to phages.

Frederick William Twort FRS was an English bacteriologist and was the original discoverer in 1915 of bacteriophages. He studied medicine at St Thomas's Hospital, London, was superintendent of the Brown Institute for Animals, and was a professor of bacteriology at the University of London. He researched into Johne's disease, a chronic intestinal infection of cattle, and also discovered that vitamin K is needed by growing leprosy bacteria.

Allan McCulloch Campbell was an American microbiologist and geneticist and the Barbara Kimball Browning Professor Emeritus in the Department of Biology at Stanford University. His pioneering work on Lambda phage helped to advance molecular biology in the late 20th century. An important collaborator and member of his laboratory at Stanford University was biochemist Alice del Campillo Campbell, his wife.

Stefan Ślopek (1 December 1914 in Skawa near Kraków – 22 August 1995, Wrocław was a Polish scientist specializing in clinical microbiology and immunology.

Virology is a peer-reviewed scientific journal in virology. Established in 1955 by George Hirst, Lindsay Black and Salvador Luria, it is the earliest English-only journal to specialize in the field. The journal covers basic research into viruses affecting animals, plants, bacteria and fungi, including their molecular biology, structure, assembly, pathogenesis, immunity, interactions with the host cell, evolution and ecology. Molecular aspects of control and prevention are also covered, as well as viral vectors and gene therapy, but clinical virology is excluded. As of 2013, the journal is published fortnightly by Elsevier.

The history of virology – the scientific study of viruses and the infections they cause – began in the closing years of the 19th century. Although Louis Pasteur and Edward Jenner developed the first vaccines to protect against viral infections, they did not know that viruses existed. The first evidence of the existence of viruses came from experiments with filters that had pores small enough to retain bacteria. In 1892, Dmitri Ivanovsky used one of these filters to show that sap from a diseased tobacco plant remained infectious to healthy tobacco plants despite having been filtered. Martinus Beijerinck called the filtered, infectious substance a "virus" and this discovery is considered to be the beginning of virology.

Escherichia coli is a Gram-negative gammaproteobacterium commonly found in the lower intestine of warm-blooded organisms (endotherms). The descendants of two isolates, K-12 and B strain, are used routinely in molecular biology as both a tool and a model organism.

Biopreservation is the use of natural or controlled microbiota or antimicrobials as a way of preserving food and extending its shelf life. The biopreservation of food, especially utilizing lactic acid bacteria (LAB) that are inhibitory to food spoilage microbes, has been practiced since early ages, at first unconsciously but eventually with an increasingly robust scientific foundation. Beneficial bacteria or the fermentation products produced by these bacteria are used in biopreservation to control spoilage and render pathogens inactive in food. There are a various modes of action through which microorganisms can interfere with the growth of others such as organic acid production, resulting in a reduction of pH and the antimicrobial activity of the un-dissociated acid molecules, a wide variety of small inhibitory molecules including hydrogen peroxide, etc. It is a benign ecological approach which is gaining increasing attention.

George Eliava was a Georgian-Soviet microbiologist who worked with bacteriophages.

Emory Leon Ellis was an American biochemist. He worked with Max Delbrück on the paper The Growth of Bacteriophage.

Anna Marie (Ann) Skalka is an American virologist, molecular biologist and geneticist who is professor emeritus and senior advisor to the president at the Fox Chase Cancer Center. She is a co-author of a textbook on virology, Principles of Virology.

Robert "Chip" T. Schooley is an American infectious disease physician, who is the Vice Chair of Academic Affairs, Senior Director of International Initiatives, and Co-Director at the Center for Innovative Phage Applications and Therapeutics (IPATH), at the University of California San Diego School of Medicine. He is an expert in HIV and hepatitis C (HCV) infection and treatment, and in 2016, was the first physician to treat a patient in the United States with intravenous bacteriophage therapy for a systemic bacterial infection.

Vincent A. Fischetti is a world renowned American microbiologist and immunologist. He is Professor of and Head of the Laboratory of Bacterial Pathogenesis and Immunology at Rockefeller University in New York City. His primary areas of research are bacterial pathogenesis, bacterial genomics, immunology, virology, microbiology, and therapeutics. He was the first scientist to clone and sequence a surface protein on gram-positive bacteria, the M protein from S. pyogenes, and determine its unique coiled-coil structure. He also was the first use phage lysins as a therapeutic and an effective alternative to conventional antibiotics.

Dr. Elizabeth (Betty) Kutter is a phage biologist based at the Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington, USA, where she is a Professor Emeritas. She led the T4 Genome Sequencing project, and organized the biennial Evergreen International Phage Biology meetings that draw hundreds of phage researchers from all over the world.